On a cold winter night in Seoul, my Korean scientist friend pointed to the full moon. “They say the moon over Korea is bigger than the moon over the US,” she said. “What do you think?”

“I’m pretty sure it’s the same moon on either side of the planet,” I said. “Our people have been there, and there’s only one.”

A while later, she brought it up again. “You know that on the Korean moon, there’s a rabbit making tteok [rice cake].”

“Yes,” I said, “I know that story.”

“So what do you have on the moon in America?”

“We see a face.”

“Aha!” she said. “So it’s not the same moon.”

Cows, chickens, and hay

Some time before, this same Korean scientist had drawn a picture for me on a Post-It note — a cow, a chicken, and some hay — and asked me to group two of the objects.

I could see what was being asked: Westerners like myself would be expected to put the cow and the chicken together, using categorical logic, while Asians would group the cow and the hay, giving primacy to the functional relationship. (A contrarian American friend put together the chicken and the hay: “I just think chickens would enjoy playing with hay.”)

Checking to see if there was any research behind this sketch test, I discovered The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently…And Why, by Richard E. Nisbett. Nisbett starts with truisms about East and West: the East is Confucian, focused on interrelationships, and sees the world as fluid and complex; the West is Greek, focused on individual objects and abstract principles, and sees the world as governed by discernible laws. What sets his work apart is that he then tests these ideas with cognitive psychological research, discovering actual, measurable differences in the ways that East Asians and Westerners — mostly North Americans — see and understand the world.

Motivationally speaking

Recently, my team at Samsung electronics moved to a new department. In our first meeting with our new manager, he pronounced himself “worried” about the quality of our work and what would be needed to improve it. And that was about it. Meeting adjourned.

From a Western perspective, the meeting was frankly bizarre. It was helpful, then, to have read Nisbett’s account of a study of motivational effects that was conducted in the United States and Japan. Subjects were given a task to complete, then given feedback: positive, negative, or none for the control group. The study measured performance and persistence on a follow-up task. Among the Americans, those who received positive feedback were most successful on the second task, sticking with it the longest; negative feedback was demotivating. But for the Japanese, the effect was the opposite: positive feedback was a license to slack off, while negative feedback was an opportunity to prove oneself.

You can see this divergence in popular dramas, East and West. Americans love the narrative of a loser who becomes a champion when a great coach teaches him to believe in himself. You can see versions of it in Rocky, The Karate Kid, Stand and Deliver, The Empire Strikes Back, Kung Fu Panda. Korean dramas often start with a humiliation by the big boss, in which the main character is belittled and dismissed. The humiliation serves as the motivating engine for the protagonist’s drive to succeed in the end. (And sometimes to marry the big boss; a Korean Karate Kid would’ve had a lot less Mr. Miyagi and a brewing romance between Daniel and Johnny.)

Restoring truth, restoring harmony

That’s not to say that you can just dismiss negative feedback from your Asian boss. Sometimes you really are being told that you’ve done badly, and you need to take it that way. But even then, there can be a different understanding of what it means to give and receive negative feedback.

In the West, when your boss yells at you — or, more likely, has a civil talk with you about your performance — there’s a kind of back and forth. At least formally, there’s usually an opportunity for you to speak up for yourself, to defend your performance or to talk about what might be causing you to fall short. Social realities notwithstanding, there’s a kind of shared understanding that what you and your boss are after is truth and justice: honest information about what’s wrong so that it can be made right. The discussion has the atmosphere of a trial: there could be an acquittal, or possibly a punishment. If there’s no action taken, the implication is that the trial’s not over. That’s what makes these conversations so uncomfortable.

A couple of months ago, our team had a meeting like that. Our manager asked us how things were going, told us we were making too many mistakes, exhorted us to try harder, and then added that we would no longer have QA oversight to help prevent the mistakes we were making too many of. To me, this was profoundly disheartening, and for a while afterward I felt sick with worry. I had trouble sleeping. Were we on probation? What consequences might be looming?

Around that time, I was lucky to have as a house guest a Swiss friend who had lived for some years in Korea, pursuing a master’s degree in traditional music performance and embedding herself in the very traditional world of Korean shamanism. She told me about a time when she’d received a dressing down from the head of her academic department. “You just sit there and listen and don’t say anything,” he’d instructed her, which she pointed out was actually helpful: she was being taught the Korean way of handling negative feedback.

A couple of weeks later, she ran into his assistant, who asked how she was doing, and she told the assistant that she was upset and shaken, worried that the department head was still angry at her. “Oh, no!” the assistant said. “He already talked to you about that. It’s finished.”

From an Asian perspective, what needs restoring is not truth and justice, but social harmony. When something has gone wrong, the senior person needs to reassert authority, and the junior person needs to reestablish humility. As the junior, your job is to sit quietly, listen to whatever’s said, and promise to do better. (“네, 알겠습니다. 앞으로 열심히 할게요. Yes, I understand. I will do better in the future.”) Together, you restore balance and harmony.

That’s why, from the Asian perspective, it made sense to take away our QA oversight. As a Westerner, I wanted the ongoing measurement. Good or bad, it would help us to restore truth and justice. That’s because I was locating the problem in our performance. But our managers were locating the problem in the disruption of harmony between management and workers. The situation could be smoothed over by taking away the disruptive measurement. If the mistakes we were making had been causing serious problems, this might not have worked, but the reality is that, like a lot of things we get invested in at work, these mistakes didn’t matter all that much. A Westerner would want some ideological justification for downgrading their significance, but for Asians the social value of the downgrade was more than enough.

Meeting in the middle

The need for harmony is also helpful in understanding how Samsung tends to respond to customer complaints.

In any big company, you’re going to get customer feedback, and some of that feedback will be produced by idiots. At Google, we would assess incoming customer issues, and at times we would determine that a given customer complaint was simply wrong. No action was needed on our part.

That’s not how it works at Samsung. The first instinct isn’t to assess the complaint on the merits. That’s Western thinking: abstract the issue from the one raising it, look for fundamental principles, make a logical judgment. Instead, the first instinct at Samsung is to find a middle ground. Can we bend to the customer a bit? There’s much less sense of a broader right and wrong. Instead, the goal is to see things both ways and move closer together: harmony.

I find that this approach is also important in working with others internally. In a Western company, a kind of debate-style approach was a reasonable way to discuss choices about design or language: we could ask dialectical questions and try to come to a better understanding of what was needed. At Samsung, I’ve discovered that my counterparts aren’t very good at that kind of discussion. There’s a lot more deferring to authority — we want to do it this way because the VP likes it — and a much greater discomfort with pointed questions or outright contradiction.

The art is to discover a middle ground that my Western mind can accept. And having attempted it for a little while, I’m much more aware of my Western tendency to jump to categorical right and wrong before it’s warranted. We Westerners tend to stake out positions and defend them, and it’s hard for us to show up the next day and admit that we can see, with a little distance, how our initial judgments were perhaps too rigid. We insist on reasons for backing down, and they have to be case-specific reasons, not social-field reasons like deference to authority or keeping the peace. It’s the American version of saving face, but I’m not sure it has much relevance in Asia.

Rabbits in motion

These different ways of seeing things — Western, categorical, abstracted; Asian, situational, interrelated — explain why Koreans have a different moon. The Western moon has a face that’s just a face and nothing else. The Korean moon is more complex: there’s a rabbit in motion, though we never see the motion; that’s something you have to infer. The rabbit is making tteok, an act of transformation — rice into rice cake — that mirrors the moon’s ceaseless cycling. It’s also a social act: rice is communally planted and harvested, and the making of tteok is a community affair. To see a rabbit making tteok is to see a web of connections, interactions and transformations. The moon is never just the moon. Everything exists in relation to everything else.

For an American, much of the fascination of living in Korea is learning to see these threads of interconnection. To get there, we have to judge less, let go of our craving for absolutes, and be willing to hover in a kind of no man’s land of uncertainty that feels very unnatural. But if you’re willing to endure the dark for a little while, you may find the Korean moon surprisingly illuminating.

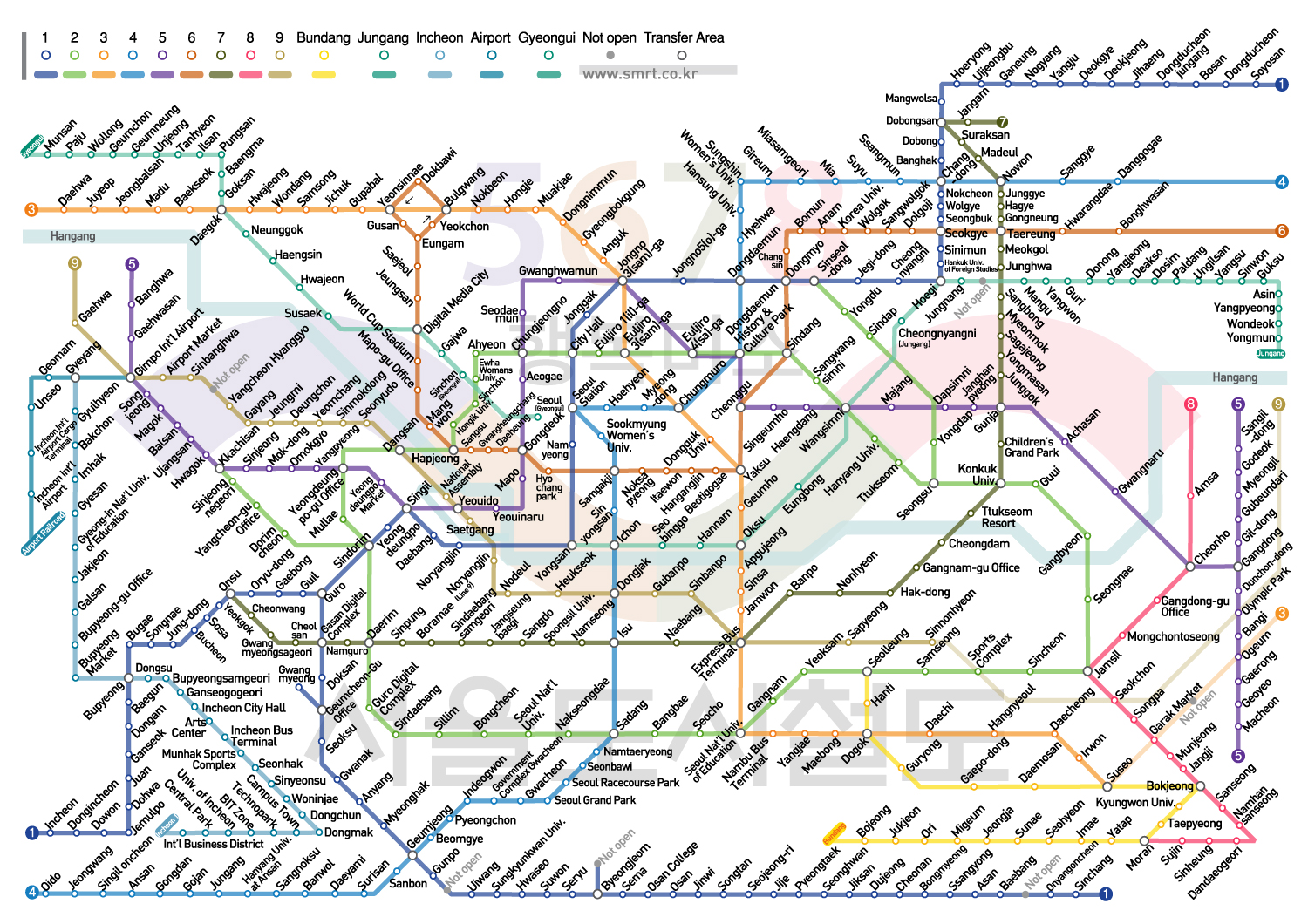

Inside the subway station, there’s a spinning wheel — a mulle (물레), a cute little visual pun on the name of the neighborhood.

Inside the subway station, there’s a spinning wheel — a mulle (물레), a cute little visual pun on the name of the neighborhood.

If you live in Korea, at some point you find yourself at Emart or Homeplus, much as anyone in America eventually winds up at Target or WalMart. The grocery sections of these big-box stores are still thriving, but the housewares are beginning to look a little threadbare. For small conveniences, people go to Daiso now — a branch of the Japanese chain is always nearby — while delivery websites like Coupang have cut into the business for big-ticket and bulky items.

If you live in Korea, at some point you find yourself at Emart or Homeplus, much as anyone in America eventually winds up at Target or WalMart. The grocery sections of these big-box stores are still thriving, but the housewares are beginning to look a little threadbare. For small conveniences, people go to Daiso now — a branch of the Japanese chain is always nearby — while delivery websites like Coupang have cut into the business for big-ticket and bulky items.