Between my home and my workplace is a mountain. I can see it from my balcony, looming up out of the density of apartment buildings. It’s there each day as we take our post-lunch constitutional around the odd little neighborhood of single-family homes that backs up against the Samsung R&D Campus. If you look at it on Kakao Map, you’ll see that there are trails running along it, but none that link Umyeon-dong, where I work, with Seocho-dong, where I live.

Still, the gap between the last marked road and the first marked trail looked to be no more than 500 meters. How hard could it be? I’ll admit that I’ve been feeling a burst of confidence since I got a surprise promotion on Wednesday. Success in one domain doesn’t necessarily translate to success in another, but what the hell? It was clear and cool and I had a couple of hours until sundown.

I was aided in the first stretch by Korea’s relentless improvements. A new ecological park is being put in, and though there are great roles of jute carpeting still to be laid, the trails are in, and the railings and signposts too. After a while, though, the trail began to loop back down. I could see on my GPS the trail that would take me home, no more than four or five hundred meters away. And up.

Between me and the trail was a steep slope, covered in gray-brown leaves. It looked slippery, and I wasn’t in the best shoes for it. Do it anyway. Once I’d gone up a ways, there could be no turning back — no sliding down those slippery leaves in the encroaching dusk. So I kept going, picking out here and there what seemed like rough bits of trail. Crows laughed at me overhead. At 5:30, an electronic Last Post wafted in from a military post on a nearby ridge.

At last I came to a windowed pillbox: a sign of civilization. Soon I found the trail, and people too: hikers, some of them elderly, making their way up. If they were still ascending, I figured I was OK to follow the sign for Somang-Tap (tap means pagoda) just 150 meters on, rather than heading directly down toward home. I passed an elevation marker at 326 meters (1069 feet), then ascended a bit more and found the pagoda: a rock pile with commanding views of Seoul to the north.

I now realize I could have followed an earlier trail fork up to the pagoda, without the scrabble through the leaves. If I ever do this again, I’ll know better. But that’s part of the fun: heading up into a mountain whose contours are uncertain and knowing you’ll just have to figure it out.

I grew up doing that on the ridges around Lucas Valley, in Marin County, California, and I learned then that you can never get too lost: just head down, and eventually you’ll find your way out. The same holds true for Seoul’s mountains, though they’re more formidable than Marin’s gentle swells. Still, back then I didn’t have a phone with a GPS and an emergency dialer.

From the peak, it was a long descent on mostly well-groomed trails, often with stairs, past the usual sorts of Korean mountainside exercise parks, until I stepped out of the woods and into the bright lights of Gangnam.

I had done it. Granted this wasn’t exactly Amundsen at the pole, but I’d rendered known what before had been a blank space on my own little map of the world. I hadn’t been sure whether you could get from one side of that mountain to the other. It turns out you can.

And once you do, you can take yourself to Butter Finger Pancake and get yourself a burger with barbecue sauce and a strawberry milkshake. Which is exactly what I did.

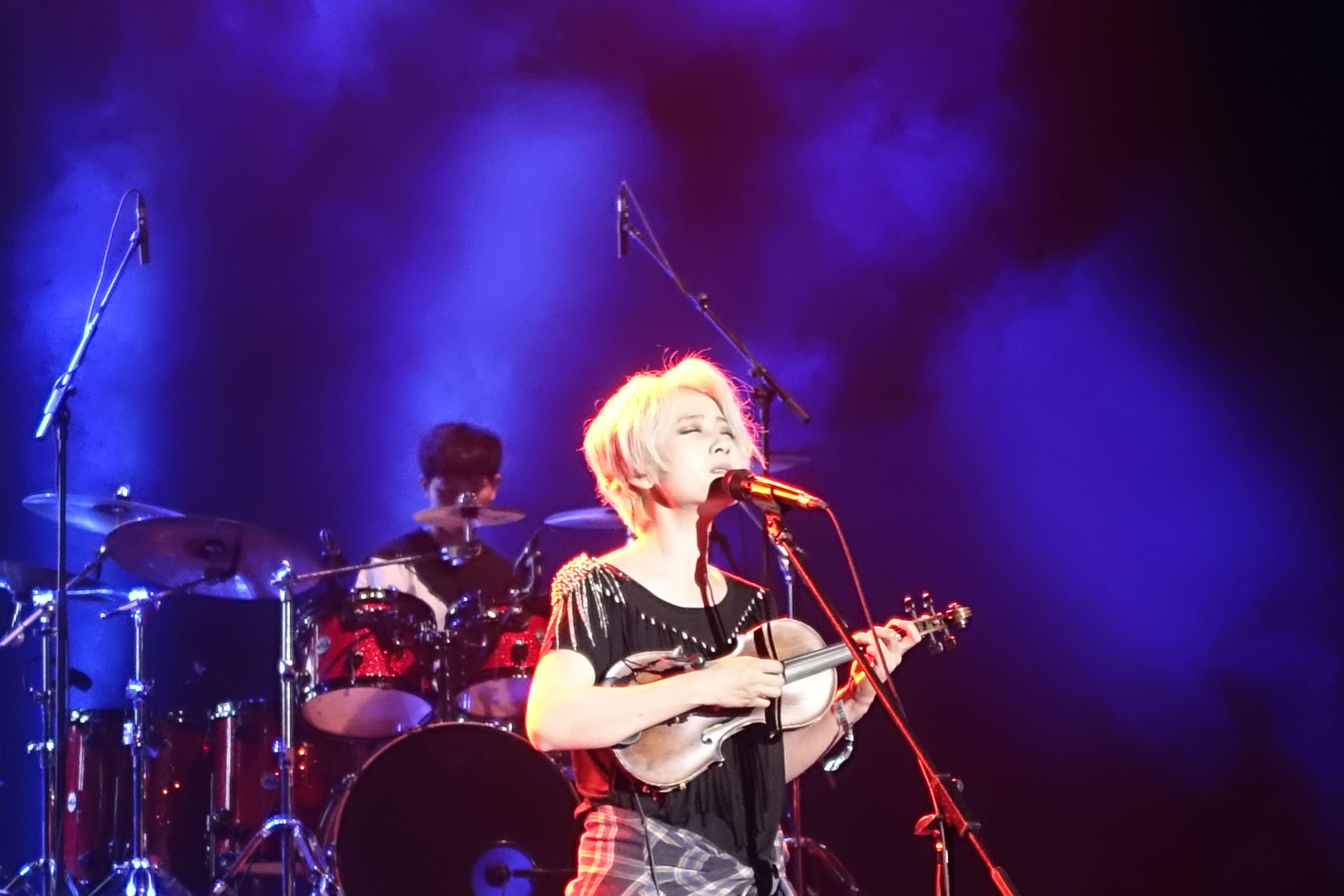

Random subway station:

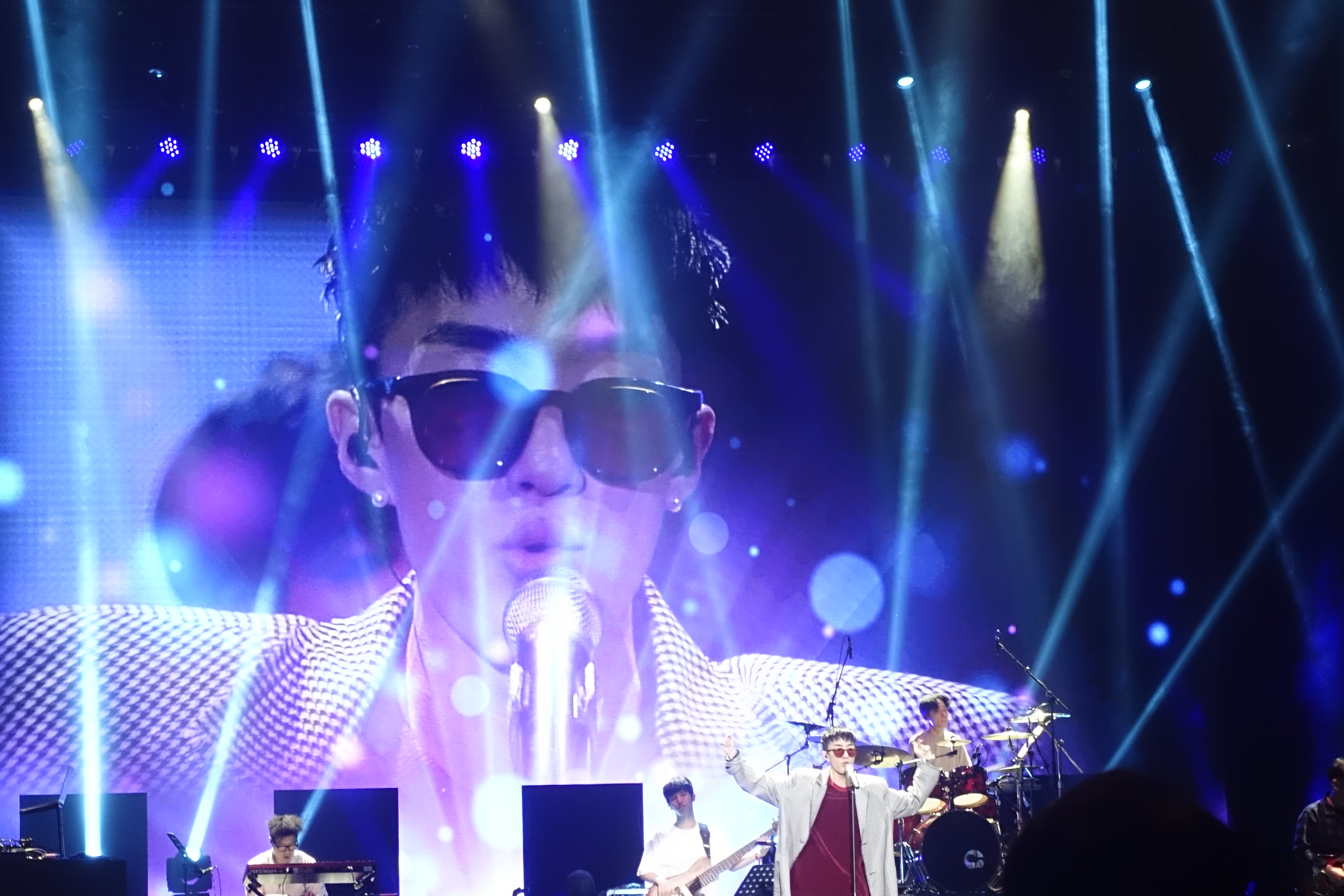

Random subway station: