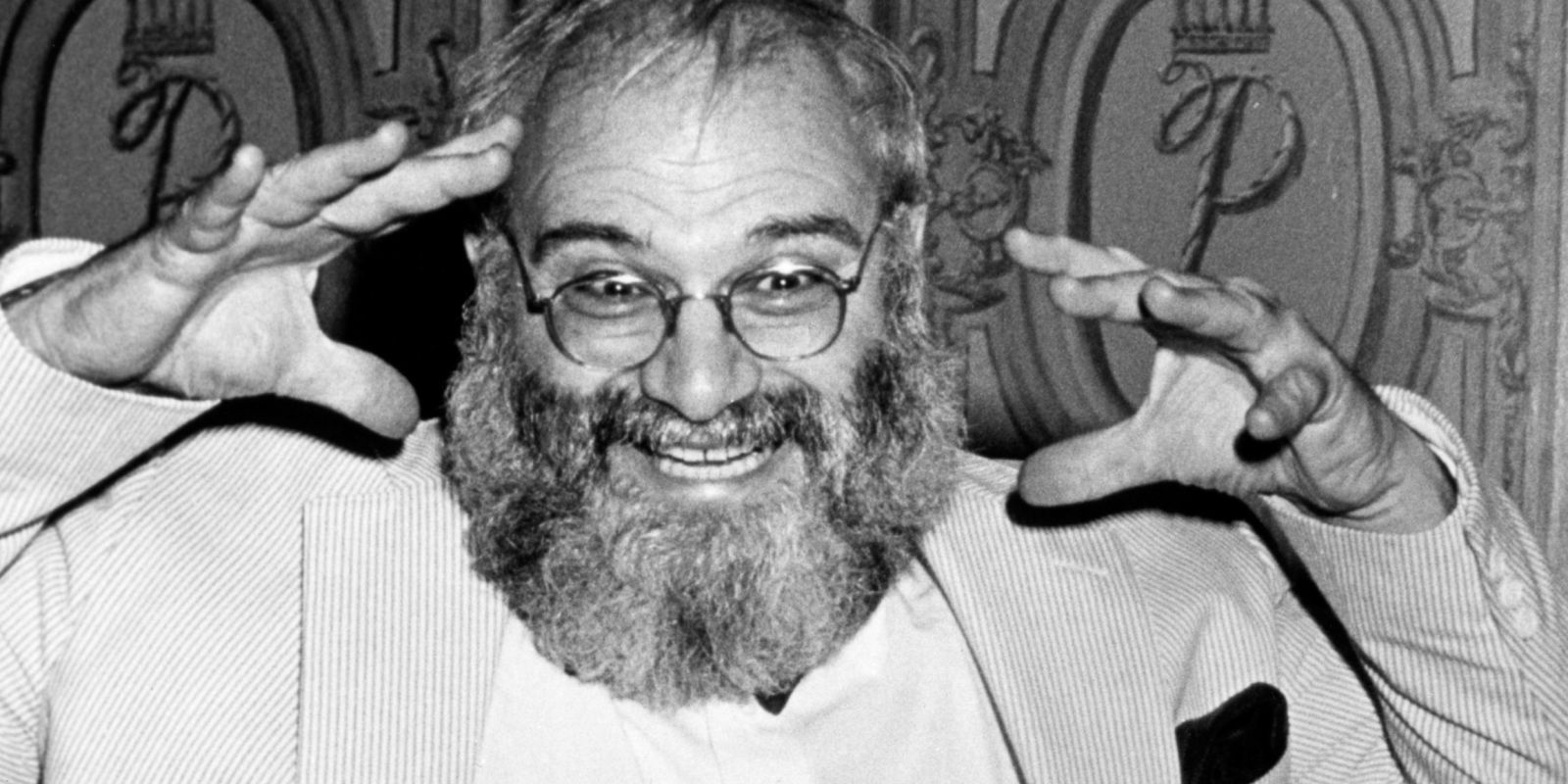

There are very few famous people whose deaths affect me, and fewer still whose deaths I worry about before they happen. But I have thought, from time to time, that Oliver Sacks must be getting on in years, and I have felt a pang at the thought that someday there will be no new Oliver Sacks essays to enliven and enlighten me.

Well, that time is coming.

I was young when I first read Oliver Sacks, still in college or maybe even high school. I must have picked up The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat off of the bookshelf in my grandmother’s office, where she kept all her psychology and spirituality textbooks (I also had my first browse through Kinsey in there).

Sacks’s insights into the mind and the self had a strong effect on me. My own father had taught me, based on his psychedelic experiences in the 1960s, that reality is a contingent thing: if a few micrograms of the right chemical can alter it utterly, how certain are we about the reality we’re seeing now? Sacks, in his writing, took that insight and gave it depth and context through his clinical tales of people who encountered the world abnormally. He did more than simply catalogue the strange, though. As a doctor, he made it his task to help people live the richest, fullest lives they could, even when they were hampered by severe and strange impairments.

My father’s mother’s father was in the ward that Sacks wrote about in Awakenings, the book that became a Robin Williams movie

, though he had passed away by the time Sacks arrived. My great-grandfather had been a society doctor when the influenza epidemic of 1918 struck. He worked himself to exhaustion and succumbed to the secondary epidemic of encephalitis lethargica — sleepy sickness — and was never the same afterwards. His decline changed my family’s fortunes and led to lifelong jealousies among his daughters.

In India, where I traveled on my own after graduating from college, I picked up Oliver Sack’s first book, Migraine, It’s not really a fun read: Sacks was not yet writing for a wide audience, and the style is clinical and technical. I picked it up in the bookshop of the Taj Mahal Intercontinental Hotel, and I read it during those first days of terrified overwhelm, coming to believe that I was experiencing migraines, or at least the migraine-like symptoms of nausea and headaches and semi-hallucinatory states. The claustrophobic quality of that book, and the sheer idiocy of choosing to read it then, remain with me as a core part of that initial experience abroad.

My grandfather, in his very last years, began running music workshops in his nursing home, bringing together his years of acting experience and his understanding of how music could reach even those who suffer from severe dementia — which included his wife, my grandmother. In this, he was informed by Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain more than any other text.

Sacks’s sense of curiosity and compassion remain a compass for me. His approach to healing has become my ideal. And whenever I see that the latest New Yorker or New York Review of Books has a Sacks piece, my mood brightens. I have rarely been disappointed. I haven’t yet read all of his books, but I expect I will — despite my earlier misstep in reading Migraine while hiding in terror in a Colaba hotel room, Sacks is usually good company on the road. And if I can approach the world — and the world inside my head — with Sacks’s trademark curiosity and kindliness, I know I’ll be doing all right.