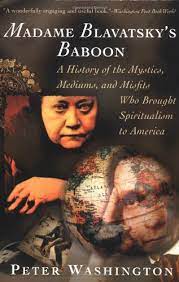

Peter Washington, Madame Blavatsky’s Baboon: A History of the Mystics, Mediums, and Misfits Who Brought Spiritualism to America (1996)

If you want to understand how the East became mystical for Americans of the sixties and seventies, you have to understand an earlier wave of spiritualism. The names may be familiar even if you’re not sure who they are: Gurdjieff, Annie Besant, Krishnamurti. None was so influential as Helena Blavatsky, who in the middle of the nineteenth century proclaimed herself both to have traveled to Tibet (almost certainly a lie) and to have been contacted mystically by Spiritual Masters who resided in the mountains of Tibet.

Why people believed this Russian fabulist is difficult to understand, and one wishes Peter Washington had expended less energy ridiculing his subjects and more energy delving into why and how they came to mean so much to their followers. One also wishes he paid more attention to the role of women in these organizations, and how that stood out from the rest of society, creating a space for female empowerment that was otherwise hard to find. Still, this is the best and most detailed account — often overly detailed — we are ever likely to get of the evolving world of spiritualism that began with Blavatsky and her Theosophical Society, then expanded out in various directions to encompass various teachers.

The influence of the Theosophists was surprising, and surprisingly widespread. Most startling is the impact it had on the places from which they claimed to derive their teachings. Annie Besant, who became president of the Theosophical Society, was also an important voice for Indian independence and an influence on Gandhi. And the Theosophist embrace of Sri Lankan Buddhism had an impact on Sri Lanka itself, reviving it there while popularizing it in the West. Walter Evans-Wentz, the translator of The Tibetan Book of the Dead, was a Theosophist. So was Alexandra David-Neel, who wrote Magic and Mystery in Tibet and inspired everyone from Kerouac and Ginsburg to Alan Watts and Ram Dass.

Washington’s approach can be frustrating. His meticulous attention to the internal disputes of the very disputatious spiritual organizations he covers at times causes him to lose sight of the larger story. There are hints that we will see how all this Theosophy business will emerge as the Age of Aquarius, but we never quite see it happen, instead concluding with vignettes of the remains of these older organizations as they limp toward the end of the 20th century, dated relics gone respectable, like Esalen or The Society for Ethical Culture. One needs to move on to Karma Cola to see the aftermath, but that work is not, like this one, scholarly, and there’s a gap. Still, Madame Blavatsky’s Baboon provides an important part of the story of the West’s fascination with the East, showing how the mostly academic and literary ideas of the oriental renaissance were transformed into a popular esotericism that continues to this day in crystal shops and yoga studios across America.