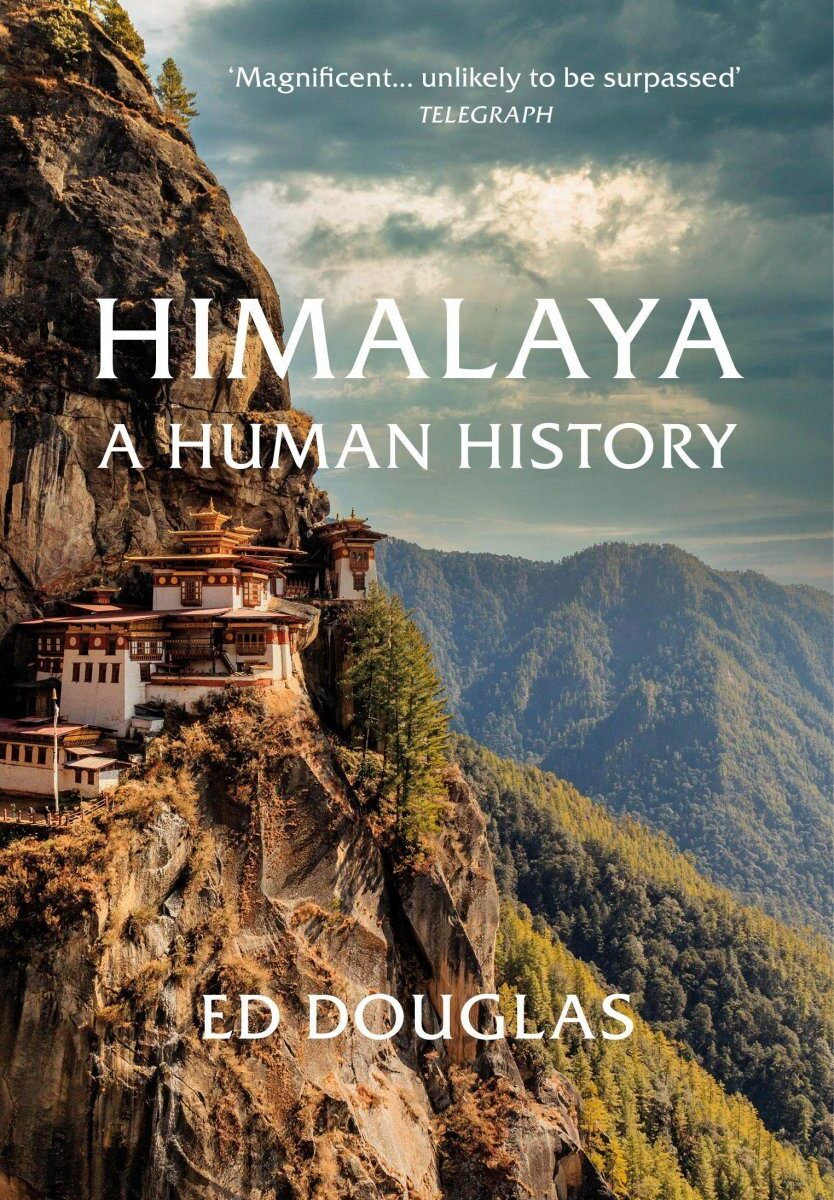

Ed Douglas, Himalaya: A Human History (2021)

In the Annapurnas, I was rarely alone. My prior idea of backpacking came from Yosemite, a park mostly closed to human habitation, where the illusion of solitude in unspoiled nature is available even on a short walk along a marked trail to a well maintained campsite. On the Annapurna trail, you’re always close to the nearest village, and even in forest passages or canyons of windswept boulders, you’re apt to be passed by a flock of goats or a train of bell-jingling yaks. The picture of the Himalaya as devoid of human life — one that comes from the expedition literature of the mountaineers who strive for the uninhabitable peaks — is a false one, as is the idea of the Himalaya as a zone of hidden and isolated Shangri-Las.

In Himalaya: A Human History, Ed Douglas puts the focus squarely on the many and diverse peoples who have called the Himalaya region their home for thousands of years. In a history that one feels obligated to call “magisterial,” Douglas tries to break out of the usual focus on Western sahibs and artificial national boundaries, albeit with mixed success. The paucity of indigenous writings and the vast wealth of Western material inevitably tips an English-language writer’s scales, and Douglas is a good enough writer to recognize a good story when he finds one. As for national boundaries, they may be artificial, but their effects on practical reality require somewhat separate tellings of the histories of Nepal, Tibet, and West Bengal (other regions such as Bhutan get less coverage).

Douglas is a fine writer who wears his knowledge lightly. There are sentences and passages so good, I wish they were mine, like this one: “Climbing is hard and unnecessary, a strange luxury.” Or this one: “We instinctively think of mountains as eternal, but they’re not. They are falling to bits and being remade like the rest of nature — like us.” He’s also, as I mentioned, a wonderful miner of stories, and he turns up some extraordinary facts, such as the occultist and Black Sabbath subject Alister Crowley nosing about Darjeeling, or the Nazis getting the swastika not from any Indo-Aryan connection but from the mosaics of Troy, or even that Nepal’s income from tourism as a percentage of GDP is actually lower than the global average, contrary to the impression most visitors get that tourism must be the mainstay of the cash economy. At times this tendency leads into odd byways, such as the long passages on botanists. Not that these aren’t interesting, but the peculiar shifts in focus can make it hard to keep the larger picture in view. There are also moments, though not too many, when the machismo inherent in being a climber and journalist sneaks its way into the writing.

Still, whatever its shortcomings — and some of them are also strengths — Himalaya is an outstanding book that will remain essential to anyone hoping to understand the region and that won’t be surpassed for a generation or more.