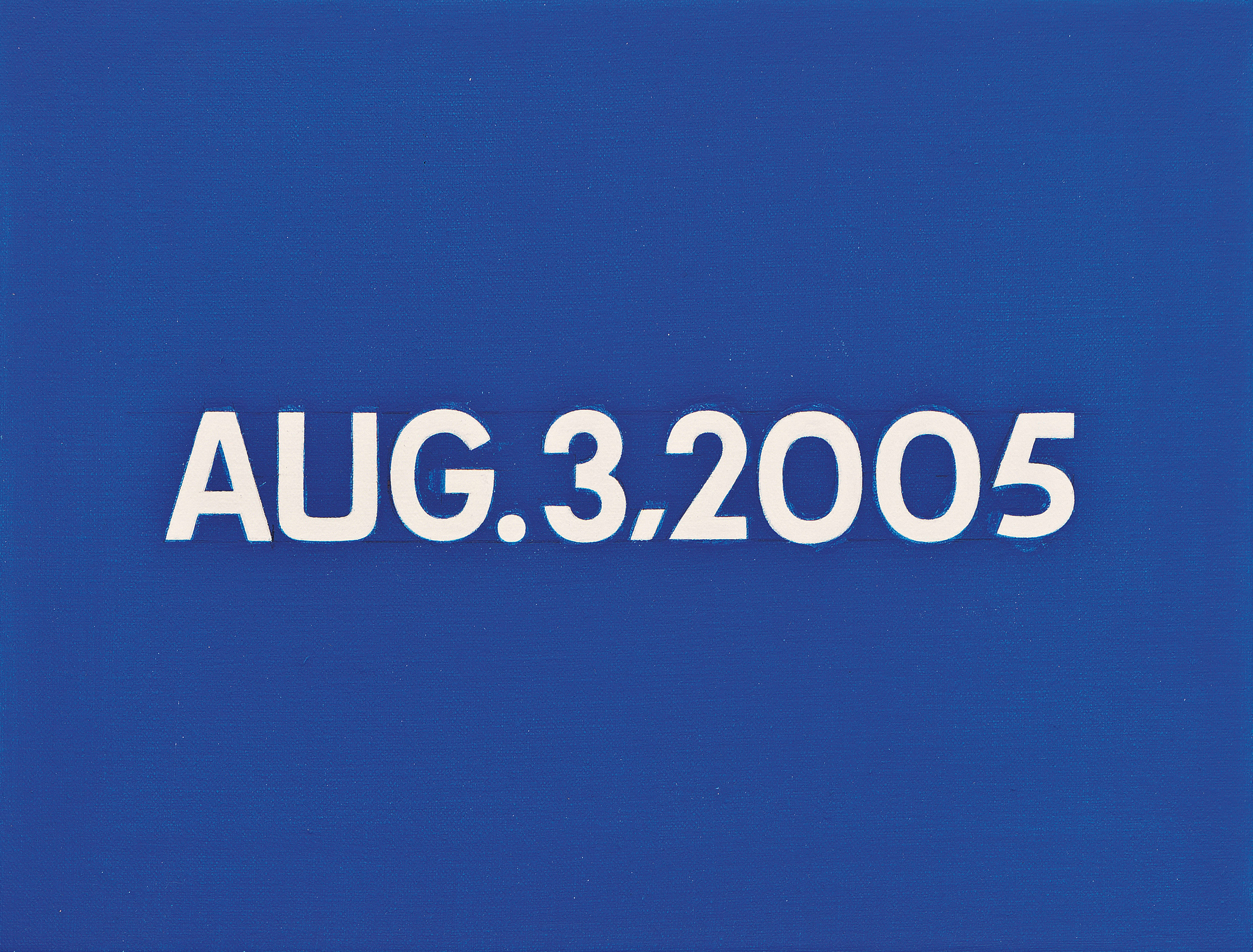

If you haven’t seen it yet, go spend some time walking up the Guggenheim ramp for the masterful show On Kawara–Silence. Kawara is a strange artist whose work makes sense only cumulatively — I had previously seen a few of his famous date paintings at Dia:Beacon and been unmoved — and the Guggenheim’s widening gyre is pretty much the perfect venue for experiencing the blank yet personal way Kawara documented the passage of time.

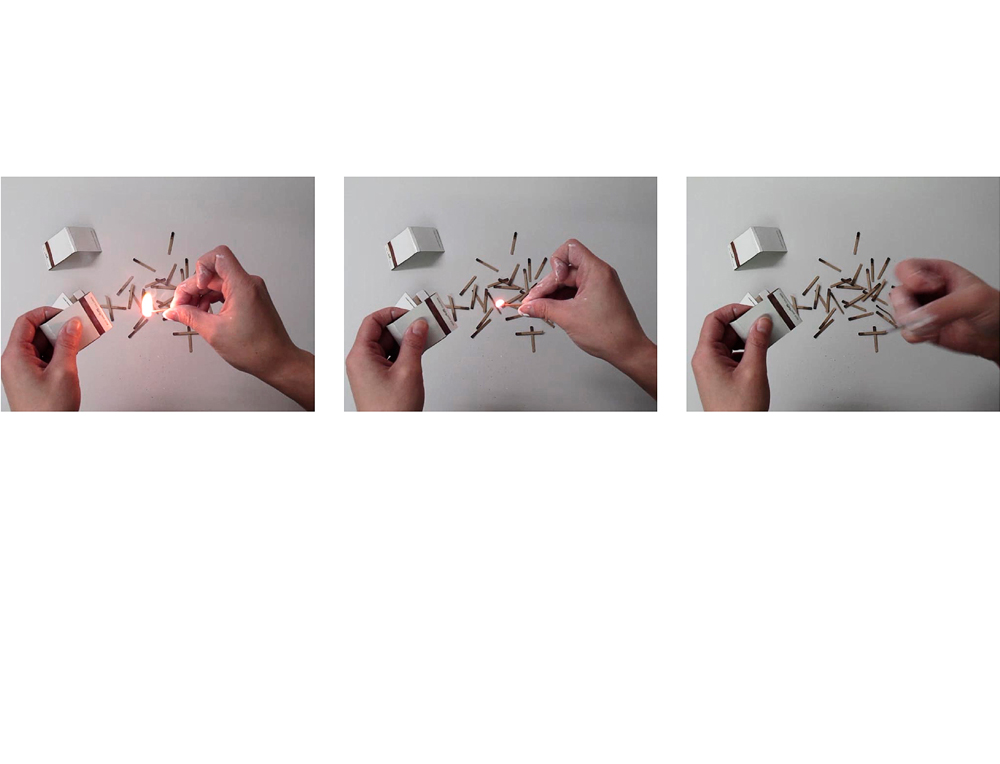

His most famous work is the date paintings: meticulously rendered, unfailingly bland paintings of the date, in whatever language and format was used wherever he was the day he painted it. But each painting also has a box that the artist created for it, lined with some not-quite-random snippet of that day’s newspaper, also from wherever he was. Kawara also sent scads of postcards stamped with “TODAY I GOT UP AT” and with a handwritten time, and then later he began sending telegrams that said simply, “I AM STILL ALIVE.” He also kept binders with lists of the people he met each day — you can play a fun little game of spot-the-conceptual-artist — and also binders of maps of where he walked each day, carefully traced out in pen.

Archive fever

I was surprised at how touching I found Kawara’s life project. The work is blank, impersonal, which creates a space for projection of our own thoughts. What must it have been like to be a Japanese-born artist traveling so often to so many places, writing postcards and dropping them in the mail each day, making paintings in hotel rooms, getting up at strange hours? And what obsessive drive led to the cataloguing of so many details so consistently for so long?

Kawara is as pure an example as you can find of Derrida’s Archive Fever, a passion for recording as a bulwark against inevitable death. Most artists are fighting a battle against mortality, but few make it so explicit (I AM STILL ALIVE, over and over, is a key part of the oeuvre of a dead man).

The poignancy of the obsolete

Part of what fascinates, though, is the extent to which technology has rendered every single one of Kawara’s obsessions obsolete. It’s hard to imagine the effort Kawara must have gone to just to get copies of maps of all the cities he was in, much less to recall and trace out his routes each day, all of which could now be handled by a smartphone and a couple of apps. Who he met each day? A few smartphone snapshots and tags would cover it. Postcards and telegrams are, of course, obsolete as well: you just tweet your location or post it on Facebook, and everyone knows you’re still alive and where you are. Various technologies can tell you what time you got up each day and can even post that information to your friends. Pasting newspapers into boxes? Who reads newspapers anymore?

If an artist today were to take on Kawara’s projects using the artist’s toolkit, it would be an exercise in willful anachronism, as much as if Kawara had chosen to mix his own mineral pigments or carve his own typescript from wood.

Archive fever vs. curation cancer

Kawara lived in an era of archive fever. The urge to catalog and archive is an enlightenment project, but it reached a sinister fever pitch in the 20th century, with the explosion of vast, mechanized government archives, often in the service of unspeakable evil. Kawara’s idiosyncratic personal archive is a kind of individual refutation of the vast state archives that had come to rule the world he lived in. State information was at once domineering and inaccessible. If you wanted to remember your own life, you had to do it yourself.

But today artists have to face a very different circumstance. Big data has made vast reams of information instantly available, manipulable. You can find anything about anything. You can listen to every album ever. No, this isn’t strictly true, but it is true that we’re buried under information. The problem is no longer access but overwhelm.

And so we move from the urge to archive to the urge to curate. How many metastasizing exercises in curation can you think of, off the top of your head? A couple of my favorites are Engrish.com and Terrible real estate agent photographs. Porn, which you used to have to seek out in illicit locations, is now, on Tumblr, turned into a system of likes, repost loops, managed subscription lists and infinite scroll.

Showing the world

In Kawara’s time, the artist’s task was to render legible and comprehensible the machine world, and you can see it in the work of artists like Dan Flavin, Richard Serra, Carl Andre, Andy Warhol. Their work enabled us to see newly and with greater insight the era of mass media, mass production and state archiving, in the way that the Dutch masters gave the burghers of the emergent Netherlands a way of understanding themselves and their place in the world.

Today the world artists have to reflect upon is the world of big data. What will this mean for art? We don’t know yet, but I expect it will involve something cleverer than embroidered Facebook posts (though I give Kathy Halper credit for taking on digitalization and feminism in her work). The conceptualists of an earlier era found ways to humanize and render into art the world in which they lived; a new generation of conceptualists will do the same for the radically changed mental landscape in which we find ourselves.