So much comes from asking the right questions.

As part of the writing project I mentioned back on my birthday, I’ve compiled a sprawling reading list to answer questions that have emerged as I’ve begun to think about my travels in India.

One of the books that’s a bit further afield is a brand new work, The Dawn of Everything, by David Graeber and David Wengrow. I’m only a little way in, but already it has helped to reframe a great deal. They argue convincingly that the Enlightenment, and European ideas of equality and freedom — concepts rarely discussed in the Middle Ages — emerged from a serious intellectual engagement with a broad Native American critique of European society. (There is also a fascinating aside in which they point out that Europe, seemingly out of nowhere, adopted a system of culturally uniform states administered by liberal arts-educated bureaucrats who passed competitive exams, and did so after Leibniz and his followers specifically cited China as a model of statecraft, and that no one ever talks about this.)

Their insights come from asking a brilliant question: Why did Europe become obsessed with liberty and equality when it did? Instead of reiterating either Rousseau or Hobbes, as most scholars of prehistory tend to do in trying to understand ancient human societies (it’s there in Guns, Germs and Steel, which came out the year I went to India), they start by asking how Rousseau and Hobbes came to be interested in a supposed state of nature, and how they came to believe that inequality was something that happened, not something that always was.

The Enlightenment as an encounter

Their answer focuses on a neglected element of the Enlightenment, which they argue was to a great extent a response to Native American critiques of Western society. They point out that one of the reasons travel literature became so popular in that era was that it revealed alternative social possibilities: the way things were was not the way they had to be.

This dovetails with a track closer to my own study, which is the idea of an Oriental renaissance in Europe, a kind of sequel to the Greco-Roman renaissance with which we’re familiar. The emergence of ancient literatures predating the Bible, especially Sanskrit literature, inspired a burst of creativity and critique in Europe in the nineteenth century that led, circuitously, to Helena Blavatsky locating her mystic Masters in Tibet, to Nietzche naming his most famous work after an ancient Persian, to the invention of Shangri La in 1931, to Nazis adopting the swastika, to people like Aldous Huxley and Timothy Leary and Allen Ginsburg and Ram Dass voyaging to India in search of wisdom, to the Beatles recording “Within You, Without You,” and to yours truly taking a Cosmic Air flight through the Himalayas.

The biggest joke

I’ve worried sometimes that all this reading — I’m 3000 pages in, with 5000 pages to go, if I don’t add any more books — is a way of avoiding the actual writing. But then I think back to my master’s thesis, a mere 48 pages that emerged from four years of graduate school and two separate research trips to Korea. It takes time to gather all the pieces.

If you want an example of the long, discursive process of creation, you can do worse than watching Peter Jackson’s four-million-hour Get Back documentary. There’s a lot of screwing around, and a lot of journeying down interesting but fruitless byways, to create “Let It Be” and “Don’t Let Me Down,” and there are also unexpected serendipities like the appearance of Billy Preston that make things work. I have to remind myself to let the journey unfold — which is something I suppose I had to do in the first place back in India.

I was struck by Paul McCartney talking about his own time in India, when he wasn’t much older than I was back in 1997. “We probably should have been ourselves a lot more,” he says, and George Harrison replies that this is the biggest joke — that they’d gone to India to find their true selves. Then he adds, “if you were really yourself, you wouldn’t be any of who we are now.”

Is that why I went to India? And was I myself while I was there? Part of being confronted by cultures so different from my own was coming to grips with who I actually was, what was me and what was merely my situation. It’s the question Conrad asks in Heart of Darkness, and it’s the question that encounters with new cultures posed to Europeans in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

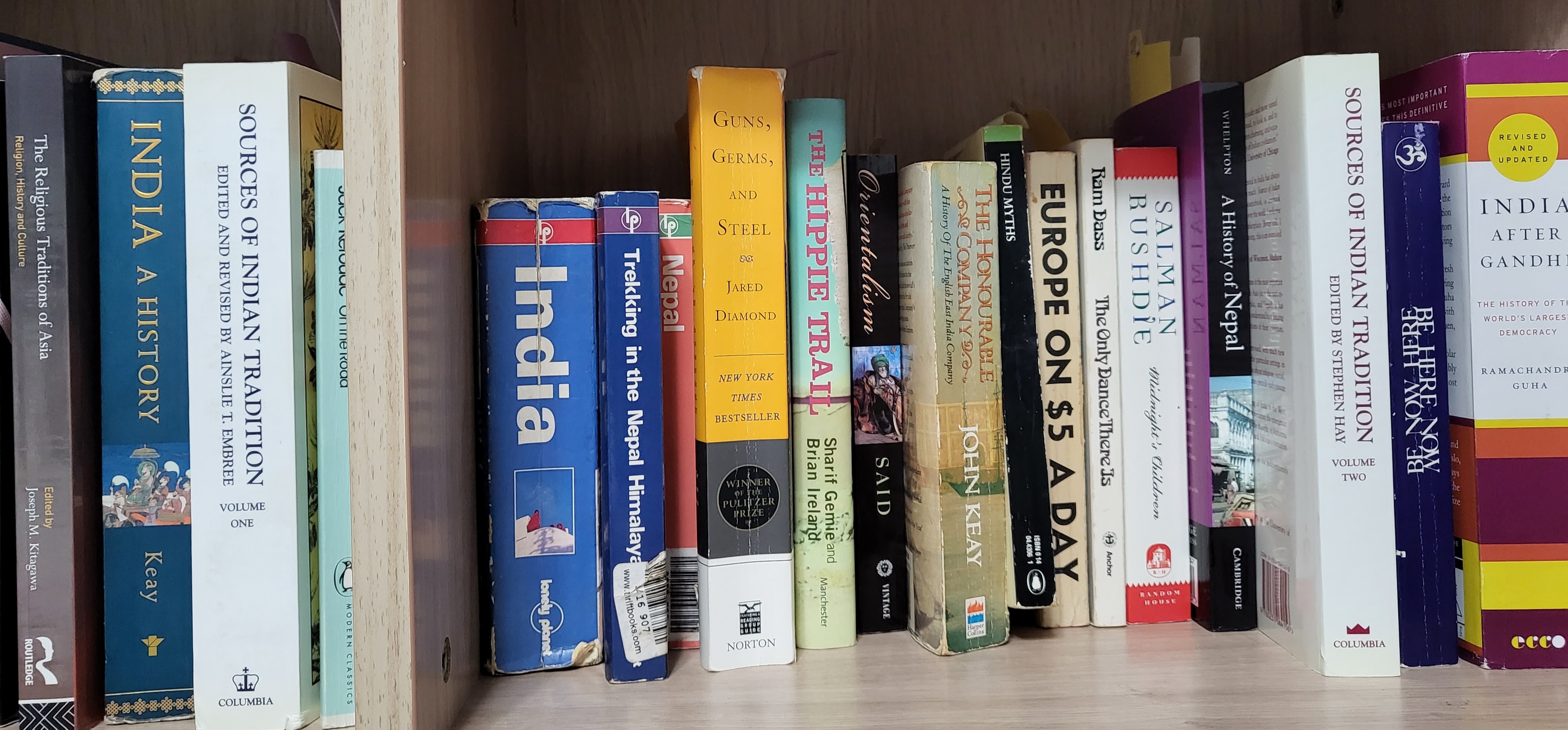

Bonus: The reading list

If this all feels a little wandery and unfocused, that’s because it is. That’s where I’m at, and it’s great to be here. More will unfold as the research continues! For those of you who want to read along, here’s the list so far.

| Conrad, Joseph | Heart of Doarkness |

| Dass, Ram | Be Here Now |

| Dass, Ram | Grist for the Mill |

| Dass, Ram | The Only Dance There Is |

| Diamond, Jared | Guns, Germs, and Steel |

| Douglas, Ed | Himalaya: A Human History |

| Eck, Diana L. | Banares: City of Light |

| Gemie, Sharif and Ireland, Brian | The Hippie Trail: A History |

| Graeber and Wengrow | The Dawn of Everything |

| Guha, Ramachandra | Inda After Gandhi |

| Heller, Joseph | Something Happened |

| Keay, John | India: A History |

| Kerouac, Jack | On the Road |

| Liechty, Mark | Far Out |

| Rushdie, Salman | Midnight’s Children |

| Rushdie, Salman | The Moor’s Last Sigh |

| Said, Edward | Orientalism |

| Saldanha | Music tourism and factions of bodies in Goa |

| Schwab, Raymond | Oriental Renaissance: Europe’s Rediscovery of India and the East, 1680-1880 |

| Washington, Peter | Madame Blavatsky’s Baboon |

| Whelpton, John | A History of Nepal |