Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity.

William Wordsworth, Lyrical Ballads

Tranquility

Some years ago, I took up traditional Korean dance for a while. At the start, it was just me and my teacher and these three old ladies, all of us practicing basic movements. At the end of the hour, when my shoulders ached and I was drenched in sweat, the old ladies would be laughing and smiling with the teacher. I couldn’t figure out how they did it.

And then, after maybe six months of doing these same dumb movements again and again — arms up, arms down, arms up, arms down — one day I felt my shoulders drop. I stopped trying and just danced. What had been so exhausting, so effortful, became natural and easy.

Two years into being a husband and a father, something similar seems to have happened. I’ve felt something slip into place. I’m not striving anymore, or trying to make it all be a certain way. I’m just doing it.

Spontaneous overflow

With that settling into my new roles came an unexpected burst of creativity.

Half my lifetime ago — I was 23 then, just out of college, and today I’m turning 47 — I spent four months in India and Nepal. I’ve wanted to write about it ever since, but somehow the writing never came.

Until now. What began as a little blog post about how technology has changed travel — digital maps and social media replacing guidebooks and backpacker cafes, that sort of thing — suddenly turned into the stories themselves.

I’d held onto these stories for years, feeling like I had no right to tell them — like they wouldn’t be interesting unless I had some excuse for them, some unifying theme or grand idea. But then I thought about all those New Yorker articles about that summer the writer worked in a grocery store or chopped wood or whatever, and I realized that stories are just stories. They’re interesting if you’re interested.

At first I worried that this sudden outpouring of writing about long-ago travel was a kind of nostalgia trip, a pining for a way of life foreclosed by fatherhood and a global pandemic. But that wasn’t it. It was something like the opposite, in fact. I’m not pining anymore for the road. I’m home. Maybe at last I can write about that long-ago trip because it’s finally over.

Recollecting

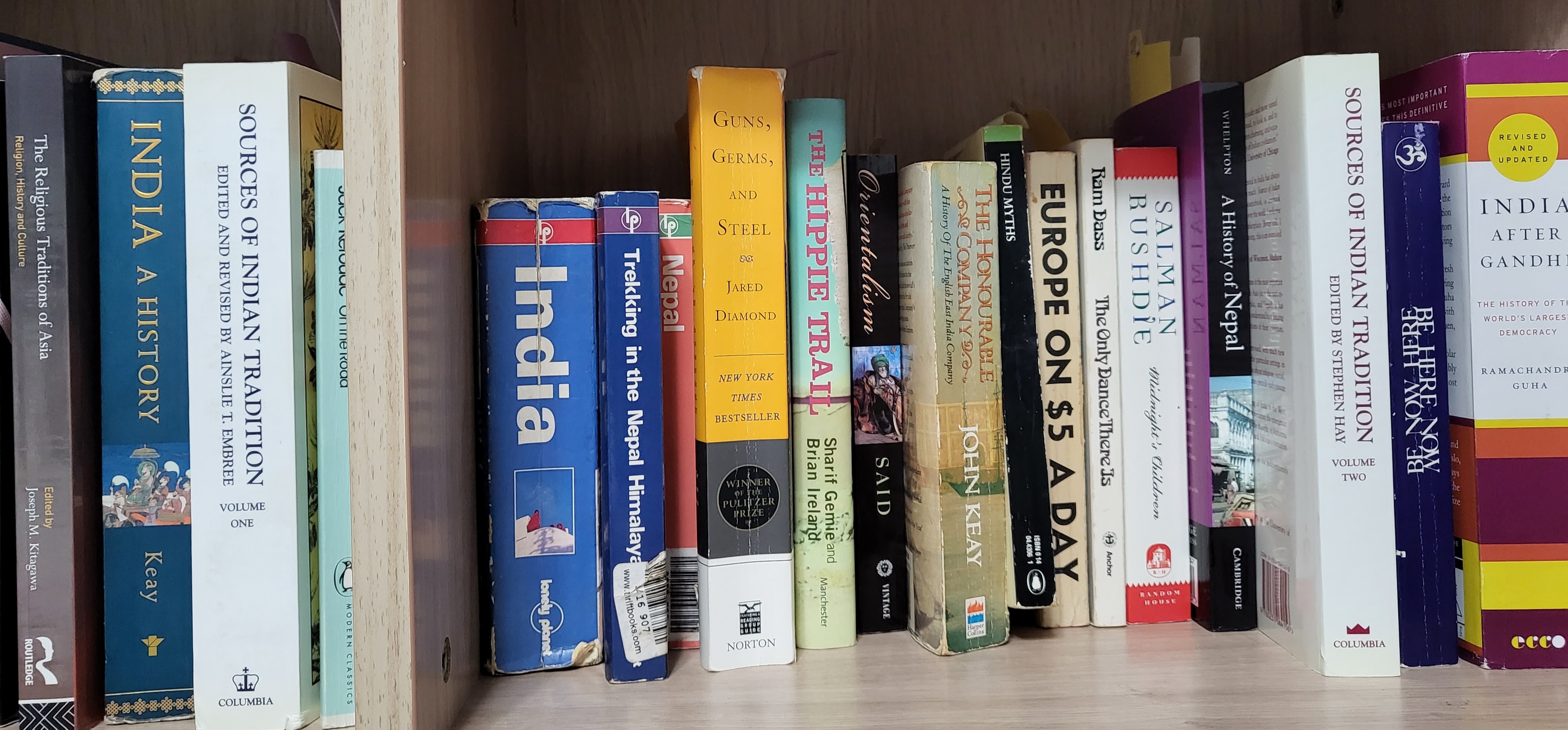

So now I’m literally re-collecting — transcribing my old notebooks (thanks Mom for taking pictures of all those pages while studiously not reading them!), getting in contact with long-forgotten travel partners (thanks Zuck!), reading histories of India and Nepal and the Hippie Trail and the Goa party scene. What will emerge from all this? I don’t know. But for now, as Toni Morrison put it, I’m writing the book I want to read.

It’s great to have a new project. My family think it’s cool that I’m writing. My daughter likes to hear the little stories about falling off a camel or getting lost in the Himalayas as they come back to me. Maybe in some way this is all for her. Being a dad means telling your kid the stories that shape her world and give her a sense of wonder to go out into it.

So this year is the year of stories, of emotion recollected in tranquility. It’s the start of a new journey, but a journey that can only be undertaken from the comfort of home.