I was very fortunate to be able to take time off and travel for 202 days in Southeast Asia in 2015-2016 — mostly in countries where the dollar stretches pretty far because of the disparity in wealth between the country where I happened to be born and the places I was visiting. I decided to give back, in a small way, by pledging a certain amount of money to charity for each day I spent in each country.

Thailand: 72 days

Because I spent the most days in Thailand, I split my donation between two charities.

My closest Thai friend was, like many Thais, reverent toward the royal family. I have my own outsider opinions about all that, but I respect my friend and her values for her own country. The Association for the Promotion of the Status of Women, under royal patronage, provides emergency shelter, health services, vocational training, and many other services to women in Thailand.

My closest Thai friend was, like many Thais, reverent toward the royal family. I have my own outsider opinions about all that, but I respect my friend and her values for her own country. The Association for the Promotion of the Status of Women, under royal patronage, provides emergency shelter, health services, vocational training, and many other services to women in Thailand.

The SET Foundation gives scholarships to those in need, with the unique principle of supporting students for a full twelve years, from elementary through collegiate studies, rather than just for a semester or two.

The SET Foundation gives scholarships to those in need, with the unique principle of supporting students for a full twelve years, from elementary through collegiate studies, rather than just for a semester or two.

Malaysia: 11 days

As you travel Malaysia, it’s hard not to notice the oil palms: acres and acres of them, a giant monoculture dominating the landscape. I didn’t visit Malaysian Borneo on my trip, but I went there recently, and I discovered the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre, which helps orangutans who’ve lost their mothers to recover and prepare for reintegration into the wild. Malaysia’s unique wildlife is precious and under threat — the oil palm plantations are pressing in, and the lumber industry wants what trees are left — but places like the Sepilok Centre have the potential to drive up the economic value of conservation and diversify the local economy by bringing tourism. And in the meantime, the preservation and restoration work they do is saving unique animals in a unique environment.

As you travel Malaysia, it’s hard not to notice the oil palms: acres and acres of them, a giant monoculture dominating the landscape. I didn’t visit Malaysian Borneo on my trip, but I went there recently, and I discovered the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre, which helps orangutans who’ve lost their mothers to recover and prepare for reintegration into the wild. Malaysia’s unique wildlife is precious and under threat — the oil palm plantations are pressing in, and the lumber industry wants what trees are left — but places like the Sepilok Centre have the potential to drive up the economic value of conservation and diversify the local economy by bringing tourism. And in the meantime, the preservation and restoration work they do is saving unique animals in a unique environment.

Vietnam: 44 days

I met my friend Christina Bui in Myanmar through a chain of travel connections, and ran into her again in Saigon and Hanoi. She works at Pacific Links Foundation, which helps to protect people in Vietnam from human trafficking — being forced into factory work, domestic work, and the like — and empowers women and communities in Vietnam. Slavery is bad and Christina is good, so this was a pretty easy choice.

I met my friend Christina Bui in Myanmar through a chain of travel connections, and ran into her again in Saigon and Hanoi. She works at Pacific Links Foundation, which helps to protect people in Vietnam from human trafficking — being forced into factory work, domestic work, and the like — and empowers women and communities in Vietnam. Slavery is bad and Christina is good, so this was a pretty easy choice.

Myanmar: 23 days

Yangon is a time capsule. Decades of misrule have had the perverse effect of preserving the older part of the city much as it was under British colonial rule. Yangon Heritage Trust is working to preserve and restore the city’s remarkable architecture before it all gets torn down and turned into KFCs, and I hope they succeed in making Yangon the gem of a city that it deserves to be, like today’s Hoi An or Penang but on a much larger scale. (Nothing specific against KFC, by the way. I threw up in the bathroom of the Yangon KFC and they were very polite about it.)

Yangon is a time capsule. Decades of misrule have had the perverse effect of preserving the older part of the city much as it was under British colonial rule. Yangon Heritage Trust is working to preserve and restore the city’s remarkable architecture before it all gets torn down and turned into KFCs, and I hope they succeed in making Yangon the gem of a city that it deserves to be, like today’s Hoi An or Penang but on a much larger scale. (Nothing specific against KFC, by the way. I threw up in the bathroom of the Yangon KFC and they were very polite about it.)

Cambodia: 8 days

Cambodia is rife with terrible NGOs and scammy voluntourism projects, so I wanted to find an organization with a good rating on Charity Navigator, and Cambodia Children’s Fund has that. They take “a holistic, family-based approach” to childhood education, which is sorely needed in this poor and damaged country. They recognize that there are root problems like hunger and violence that can undermine education, so they try to deal with all of these issues as they help young people get the schooling they need and deserve.

Cambodia is rife with terrible NGOs and scammy voluntourism projects, so I wanted to find an organization with a good rating on Charity Navigator, and Cambodia Children’s Fund has that. They take “a holistic, family-based approach” to childhood education, which is sorely needed in this poor and damaged country. They recognize that there are root problems like hunger and violence that can undermine education, so they try to deal with all of these issues as they help young people get the schooling they need and deserve.

Laos: 23 days

Perhaps the most dangerous thing I did in Southeast Asia was go for a walk in Laos.

Perhaps the most dangerous thing I did in Southeast Asia was go for a walk in Laos.

Laos has more unexploded ordnance (UXO) per capita than anywhere else on earth, a sorry result of a decade of American bombing during the Vietnam War. On a tour of the Plain of Jars, on a trail that was supposed to be cleared, my guide suddenly jumped back and pointed. “That’s a cluster bomb detonator.” He then told me how his brother died: he’d gone fishing and was cooking up his catch in a rice field when the heat triggered an old pineapple bomb that took his head off.

I split my Laos donations between two organizations that deal with the ongoing disaster my country left behind. COPE gives people their lives back by providing prosthetics and rehabilitation to UXO survivors and others with mobility-related disabilities, while the Mine Awareness Group (MAG) works to demine Laos (and other places) and educate the local people about how to avoid UXO accidents, thereby reducing COPE’s potential clientele. I saw both organizations at work in Laos, and at one point even had to stop driving while MAG blew up some UXO they’d found in a field — a field that, when cleared, could provide food and income to a Laotian family.

I split my Laos donations between two organizations that deal with the ongoing disaster my country left behind. COPE gives people their lives back by providing prosthetics and rehabilitation to UXO survivors and others with mobility-related disabilities, while the Mine Awareness Group (MAG) works to demine Laos (and other places) and educate the local people about how to avoid UXO accidents, thereby reducing COPE’s potential clientele. I saw both organizations at work in Laos, and at one point even had to stop driving while MAG blew up some UXO they’d found in a field — a field that, when cleared, could provide food and income to a Laotian family.

Indonesia: 18 days

Yayasan Usaha Mulia (YUM) – Foundation for Noble Work has been around a long time and does holistic community work focused on education and alleviating poverty. Finding a good charity in Indonesia — especially one that wasn’t religiously based — was a bit difficult, but YUM seems to have a decent track record.

Yayasan Usaha Mulia (YUM) – Foundation for Noble Work has been around a long time and does holistic community work focused on education and alleviating poverty. Finding a good charity in Indonesia — especially one that wasn’t religiously based — was a bit difficult, but YUM seems to have a decent track record.

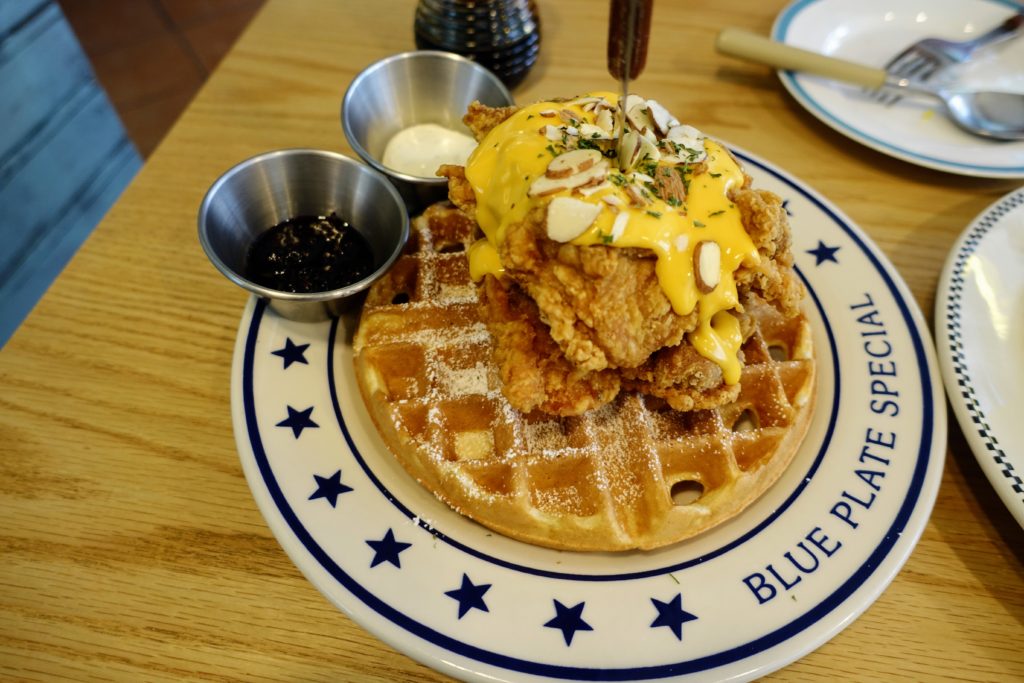

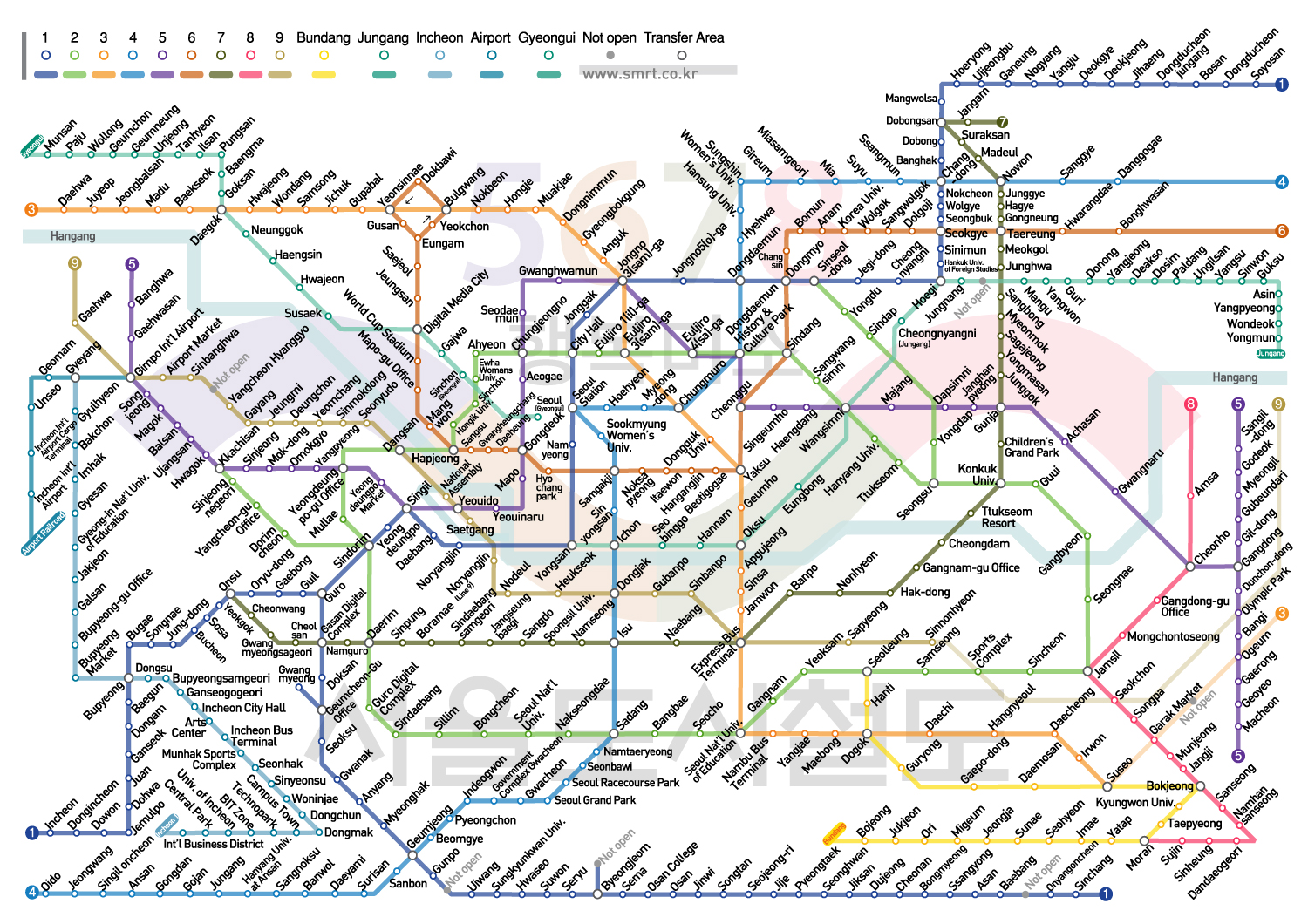

Singapore: 3 days