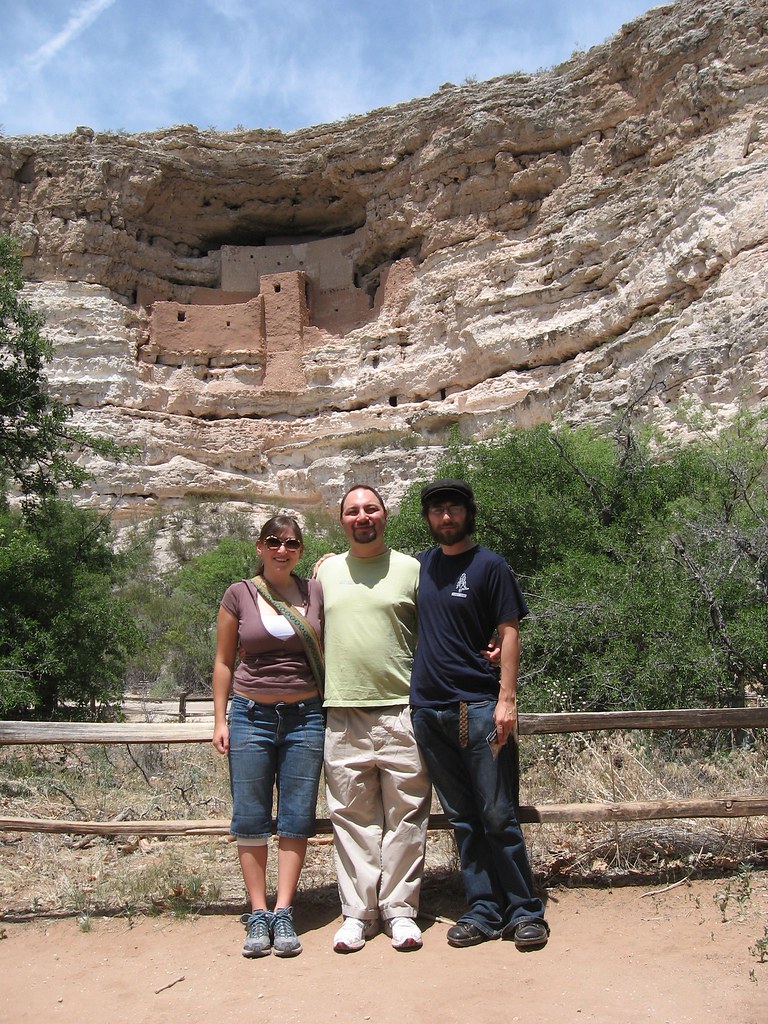

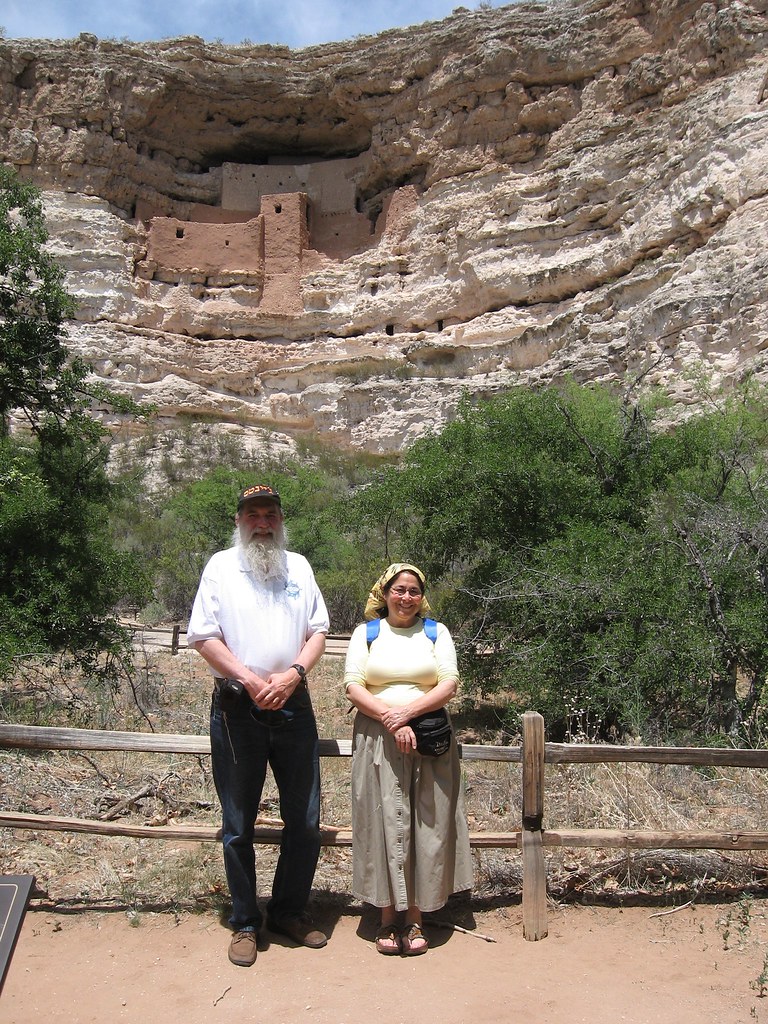

I’m back at work today after a week and a half in Arizona to celebrate my sister’s graduation from ASU (BA in art history) and to spend some time with my family in Sedona and at the Grand Canyon. Here are some of the pics my sister sent me.

[from philly to phoenix]

Now I know Philly doesn’t exactly have a reputation as a sexy destination. But Jenny got to know Center City pretty well during her project down there with Cigna, and she wanted to share it with me, and she had the points on her credit card to get us a free night at the DoubleTree, so down we went.

I have to admit that I was thoroughly charmed. Philly is a beautiful city that has preserved much of its colonial architecture and is full of ornate 19th-century confections such as City Hall, not to mention a thoroughly respectable skyline of elegant modern towers. On a beautiful spring day, Jenny and I were able to stroll through much of Center City, and I think we both most enjoyed the narrow, cobbled lanes full of colonial brick row-houses and cherry blossoms. Unlike New York’s Dutch-style homes, Philly’s have no semi-basements, which means there’s no call for the great big stoops so familiar in Brooklyn, which means the houses don’t have to be set back so far from the street. As opposed to Brooklyn’s stately quality, Philly’s old houses, largely free of ornamentation, create an atmosphere of friendly, practical intimacy. Indeed, part of the charm of the historic district is that most of even the oldest buildings are still living homes. Over in the downtown shopping district, we visited the Macy’s, which is home to the Wanamaker Organ, the world’s largest operational organ, which I can now attest puts up a hell of a racket when it’s going full-bore.

Philly has also grown into something of a foody town, and we ate exquisitely at a small Italian restaurant called Mercato. It was a Saturday night, Cinco de Mayo and the finest weather imaginable, so every decent restaurant was packed; we had to wait for a seat, but we sat on a small stoop in the lovely night and took in the passers-by. The Center City crowd seems to be well-healed yuppies, with a strong gay community and a fair number of families raising kids.

On Sunday we went to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, an elegant neoclassical palace on a hill, with excellent holdings in European art from the Middle Ages forward, in Asian art and in American work as well. Distinctive to the Philly Museum is its emphasis on architecture, with room after room of full interiors — a Chinese Buddhist temple, a Medieval cloister, a Parisian interior from the 19th century, a Dutch merchant’s bedroom — giving the art a rich context. Nor are the works themselves anything to sneeze at. Their Medieval collection is excellent, and there’s a rich selection of works by many of the European masters, particularly of the Impressionist and modern periods. And I was pleased to discover that they have devoted some meaningful attention to Korean art in recent years, managing to acquire a number of works that are actually good, including some fine Joseon furniture, pottery and painting and a bit of good contemporary art.

So we had a lovely weekend in Philly, and I now know Center City. As for the sprawling rest of the city, I haven’t the foggiest what goes on there.

*

I came back home with a brand new cold, unfortunately. I suppose I’ll be a bit of a disease vector when I take this thing out to Phoenix, Arizona, on Wednesday. I’ll be going for a week and a half to celebrate my sister’s graduation from ASU and do some family vacationing around Sedona and the Grand Canyon. So posts will be sparse.

[whopper vs. whopper]

Ever order something at a fast food restaurant because the photo on the menu board looks good, and then feel cheated when you get some lumpen beige thing? This phenomenal series of photos is photographic proof that that’s just how it works. (Via BoingBoing.)

[goin’ to chicago]

Chicago by Sufjan Stevens (Illinois)

Today is Jenny’s first day at her new consulting gig in downtown Chicago, where she will be spending three to four days a week for the rest of the year and possibly beyond.

I know next to nothing about Chicago. I have only been there once, for an evening, and spent it in a depressingly cheesy jazz club. I know they have deep-dish pizza, that the Blues Brothers and Ferris Bueler lived there, that it once burned to the ground long ago, that it was a magnet for the westward migration of Polish and German and Irish and Italian immigrants and a magnet for the northward migration of African-Americans. Martin Luther King, Jr., did poorly there. The buildings downtown were steam-cleaned in the eighties for the filming of The Untouchables. Chicago blues is an electric variety that helped create rock and roll and that has a dangerous tendency to fall into wanky self-parody. Chicago is America’s second city, and the moniker “Windy City” comes from a reference to its politicians, not its weather.

And that’s about it. Trivia, really. None of the living feel of the place. You could drop me in the middle of Jaipur or Seoul without a map and I could find my way, but I’d be hopeless in Chicago.

But like most great cities, Chicago is also a city of the mind, a target of the imagination. In “Baby are Yeng,” Nancy Jacobs and Her Sisters (about whom I could find basically no information) give South African bounce to the very African-American yearning to leave the Jim Crow South behind for better odds in the big city, in what has to be one of the catchiest tunes ever. (Via the inimitable Locust St.) And in “Chicago,” Sufjan Stevens manages to invoke both that city and New York in a story that I don’t understand, but that moves me anyway.

Jenny, I’ll miss you when you’re far away. Have fun!

[secrets and food]

I’m walking down Sixth Avenue on a Friday evening after work, hurrying to my therapist, a blue-green headache crawling over from the back of my skull towards my right eye. I’m hungry. I want meat. The Halal Foods truck isn’t open yet, and the cart in front of the Best Buy on 23rd has nothing but pretzels. Time is running short. I duck into the CVS on 25th and browse the snacks. Jerky is ridiculously expensive. I settle for a cannister of Slim Jims. They’re greasy in a queasy way, but they have the mix of salt, fat, protein and umami that I’m craving. They get me through.

I’m walking down Sixth Avenue on a Friday evening after work, hurrying to my therapist, a blue-green headache crawling over from the back of my skull towards my right eye. I’m hungry. I want meat. The Halal Foods truck isn’t open yet, and the cart in front of the Best Buy on 23rd has nothing but pretzels. Time is running short. I duck into the CVS on 25th and browse the snacks. Jerky is ridiculously expensive. I settle for a cannister of Slim Jims. They’re greasy in a queasy way, but they have the mix of salt, fat, protein and umami that I’m craving. They get me through.

I stuff the cannister in my bag, and when I get home, I slip it into a dresser drawer. I don’t want Jenny to see. I’m ashamed of having bought such down-market junk food. I’m afraid she’ll think I’m disgusting for eating it, for wanting to eat it. There’s no reason she needs to know.

This is the insanity from which I am working to recover. I confessed to Jenny last night about the Slim Jims, though it hardly counts as a confession considering that I hadn’t done anything wrong. It made her laugh. What’s especially ridiculous about the whole thing is that I went with Jenny to McDonald’s on Saturday to indulge her particular junk food craving. Why would she have a problem with mine? But I had to confess because the mechanism of this secret-keeping — the shame, the hiding, the justification — was exactly the same as the mechanism for much bigger, more serious secrets.

This incident has got me thinking now about my relationship with food. I don’t think of myself as someone with an eating disorder, though I tend to overeat from time to time (like most Americans) and to treat emotional distress with tasty treats (also like most Americans). But my psychological relationship with food is nevertheless tangled.

I grew up in Northern California in the late 1970s and 1980s, an era when food virtue replaced religion for many people. Terms like “macrobiotic” and “Pritikin” and “organic” were in the air, and food allergies were just coming into fashion. For children, the complex restrictions, and the earnest moral tone that went with them, was often bewildering, especially in group settings. (I still harbor a bitterness about efforts to convince me that carob was just like chocolate. It is not, and any idiot could taste the difference. It was insulting.)

My parents were pretty chill on the health food front, but beginning in my early childhood, a strange, isolating, ever-tightening net of restrictions began to enclose me, one intimately tied to morality and virtue: the laws of kashrus. At first we just kept kosher style, which was easy and kind of fun, offering a whiff of superiority without demanding much. We didn’t eat pork and we kept our milk and meat separate. No big. It meant we were better people.

But gradually the rules became stricter, and eventually we went wholly kosher: separate dishes for milk and meat, eating only products that were labeled with a hechsher, subscribing to newsletters that detailed the ongoing debates about even hechshered foods, waiting an hour (then three, then six) after eating meat before eating anything with milk in it. There were no kosher restaurants in Northern California, so that was out too. Chinese food was gone from my life. Around friends, I was expected to keep track of a vast library of unacceptable treats and shun them when offered. No more Oreos. No more Starbursts. And there was always the danger that a beloved product would slip into doubt. Worse, my parents would make an exception for something they loved, and then one day decide — arbitrarily, as far as I could tell, and certainly without consulting me first — that the exception had to end.

Holidays brought other restrictions. Every couple of months, fast days came around, and from age 13 I was supposed to go either from sunset to sunset or from dawn to sunset, depending on the particular fast, with neither food nor drink of any kind. Before fast days, including the highly sacred Yom Kippur, I would sneak extra snack food into my room, but I was always careful tokeep myself hungry enough to eat a lot when the fast ended. Passover was a week of confusion and despair, as the available foods were limited to the flavorless and the difficult; I lived primarily on macaroons, leftover roast from the Seder, and a sort of matzah-based breakfast cereal my mother concocted, and which was always under threat from a potential restriction on gebruchts, or matzah that has become wet.

Added to those food issues was my father’s ongoing hectoring of my mother about her weight. She wasn’t ever obese or even very chubby, but neither was she the hot-bodied 19-year-old he married and painted in a bikini, and I don’t think my father accepted easily that my mother’s body was simply never going to return to the state it was in when she was getting catcalls across Europe in 1966. And none of us could help but be aware of my maternal grandmother’s long struggle with serious obesity, punctuated by crash diets and involvements in OA.

That this way of life led to secrecy and dualism is hardly surprising. I wanted to be a good son and a good Jew. I also wanted to eat things that tasted good. What alcohol or cigarettes or pornography are for some kids, bacon and Nabisco products were for me. Except that in other people’s homes, these things were completely normal. When Dan down the street got his Easter basket full of Starbursts and offered to share, I didn’t say no. By the time I reached adolescence, when constant hunger and rebellion are pretty much the norm anyway, I was willing to break food rules whenever I could. In high school, I would drive down to the mall and eat a big plate of Chinese food for lunch, savoring the pork dishes. It wasn’t that I went out of my way to eat pork specifically, but that I wanted to eat what I wanted to eat, without restrictions from my parents.

And I wanted to eat in restaurants. I wanted to be normal. When Joey got into Thai food — his parents were much slower to adopt the full religious regimen — I wanted to know what he was excited about. My parents actually mocked the food freaks with their semi-imaginary health fragilities, somehow never realizing that they’d turned me into the nerdy kid with the milk allergy. (Later, in my pot-smoking years, when I shunned tobacco-mixed spliffs because tobacco gives me headaches and tastes lousy, I usually felt it necessary to make some comment like, “I hate to be the kid who says, ‘I cannot have milk because I have a lactose intolerance,’ but I really don’t like tobacco.”) It was one more of the many, many ways that Orthodox Judaism isolated me and kept me alienated.

In my teen years, I would disappear into my room with a box of cookies and not return it to the kitchen. Did it take me a week to finish, or two days, or did I finish it that night? I kept the pace of my indulging secret from my parents so that they couldn’t scold me for overeating, or for the cost of my eating.

It was also in this period that I learned from my peers to feel moral and political shame around eating. My high school had militant vegans. Eating meat was bad. Eating environmentally damaging foods was bad. Mostly I made a mockery of this sort of thinking, but it affected me. And perhaps because of my own upbringing, I have found myself attracted to or in relationships with food moralizers quite often. Berit was a vegetarian who thought seasoning was creepy; T had complex ethics and aesthetics around food that kept me nervous and uncertain. To an extent, I think I hid the Slim Jims from Jenny because T might have scolded me for eating them. And I have sometimes waited for Jenny to go to bed so that I can snack without incurring her fear that I’ll get diabetes like her father.

But I like Slim Jims from time to time. I like Hormel chili. And more importantly, I have a right to like whatever I like. Food shame and food secrecy are habits that I need to break. They are part of my systems of indulging my own desires through secrecy rather than being open about what I want and need. And that has to change.

[meetings]

I need 12-step meetings.

Last night was my first in a week, and that’s the longest I’ve gone between meetings since I began my recovery 51 days ago. I missed my usual Sunday and Tuesday meetings to spend time with Jenny and her parents, who were visiting from Los Angeles, and I had a lovely time with them. On Sunday we did a walking tour over the Brooklyn Bridge, and Tuesday night we went to the New York City Ballet for opening night of the spring season, an exquisite performance of modern classics by Balanchine.

This was all good, but by Wednesday and Thursday I was getting mawkish. Jenny had spent a lot of the time with her parents exploring her own past and theirs, and this led me into sentimental considerations of my own situation, especially as it pertains to my recovery from addiction. I was falling into the addict’s trap of looking back on the active addiction through rose-colored glasses, seeing it as sexy and adventurous and romantic. I was also feeling deeply lonely, and all of this was very much a self-absorbed mooning.

Last night’s meeting was a powerful corrective. There were several newcomers, all feeling the raw hurt and despair and terror and shame that I felt when I came in less than two months ago. There was nothing pretty about the pain they were feeling or the damage they felt so much shame for having done to their lives and to the people closest to them.

But there was hope, and I was not alone. We were in this together, and for 90 minutes I was pulled out of myself. I listened well last night and identified with much of what I heard. I was present for others, and they were present for me. And in those moments of being present for others, the whole question of life’s purpose simply disappeared.

Amazingly, what I experienced briefly last night is exactly what is described in the Ninth Step Promises (pp. 83-84 of the AA Big Book), which are read at every meeting:

If we are painstaking about this phase of our development, we will be amazed before we are half way through. We are going to know a new freedom and a new happiness. We will not regret the past nor wish to shut the door on it. We will comprehend the word serenity and we will know peace. No matter how far down the scale we have gone, we will see how our experience can benefit others. That feeling of uselessness and self pity will disappear. We will lose interest in selfish things and gain interest in our fellows. Self-seeking will slip away. Our whole attitude and outlook upon life will change. Fear of people and of economic insecurity will leave us. We will intuitively know how to handle situations which used to baffle us. We will suddenly realize that God is doing for us what we could not do for ourselves.

Are these extravagant promises? We think not. They are being fulfilled among us — sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly. They will always materialize if we work for them.

I’m not saying that I was fully conscious of every one of these promises being fulfilled in the moment, and I’m definitely not saying that these promises have come true in my life overall. I haven’t earned them yet, for one thing; there’s still a long journey for me before I take on Step Nine.

What last night taught me, though, is that the Ninth Step Promises are a wordy way of describing a state of Zen. Notice that they’re not promises about the world beyond the self, but about one’s own perception and understanding. In a Zen state, there is no self-seeking, no worry, no fear, only freedom and happiness and serenity and peace. We enter into these states when we are fully engaged in what we are doing, fully present in the most profound sense. That kind of engagement is what I need to bring into my life, and I believe that the Twelve Step tradition is right to suggest that service to others is a powerful way to achieve it.

Looks like something I will need to explore further.

[false memories]

If you read this, if your eyes are passing over this right now, even if we don’t speak often, please post a comment with a completely made up and fictional memory of you and me. It can be anything you want — good or bad — but it has to be fake. When you’re finished, if you would like you can post this little paragraph on your blog and be surprised (or mortified) about what people don’t remember about you.

I picked this up from T and thought I’d post it here, even though no one ever responds to my memes. Please, post a lil sumpin sumpin.

[purpose]

I have been struggling of late with the question of purpose in life.

This is not a new question, or unique to me, but sobriety has thrown it into a new light. I am making an effort to live a life of rigorous honesty, which is a pretty radical departure from what I’ve done up to now. I am no longer masking reality with drugs, and I am faced with accepting — deeply accepting — that certain long-cherished fantasies are nothing more than that.

I think most of us carry around an idea of Eden. Mine is a sort of amalgam of Weetzie Bat and the forest of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, set in the Northern California redwoods, with a Noe Venable soundtrack, and populated with beautiful mysterious girls who fall in love with me and lead my on psychedelic adventures.

This is, of course, not a place I have ever actually experienced, but I have touched at its tantalizing edge often enough to cherish the dream and even half believe in it. I think of certain warm summer nights with Amber and Kim and Ashley-Jayne, drinking borgias on the back porch of Caffé Nuvo in San Anselmo and taking over poetry night for ourselves. I was very young then, but old enough to have confidence and sexual experience, and there was so much money and so much time.

And yet this memory is a lie, or at least a highly edited version of what really happened. Yes, those nights were beautiful, but much of that summer was spent in Amber’s apartment, wallowing in the stench of her mother’s chinchillas and arguing over how to fill our empty days and waiting, always waiting, for Amber to relent and let me fuck her. I did finally manage to find sex later in the season, with others. First there was that one night with Ashley-Jayne, which was not enough and left me lonely. Later there was my week-long adventure with Olga the Russian scientist, which felt naughty and daring, and was the first time I had the now familiar experience of simultaneously wanting sex and wanting to escape from the person I’m having it with. These were not terrible experiences, but I have given them the rosy glow of romantic narrative — indeed, I gave them that romantic narrative as they were happening — and that is a deep dishonesty that has colored my whole life since.

There are other moments that I cling to in my past, often involving some kind of erotic or drug-related adventure, that are similarly falsified and glorified in my memory: the summer I was a counselor-in-training at camp and fell in love with the beautiful girl from Israel, and better yet, was somehow suddenly attractive enough that she fell in love with me; the night in New Orleans on my Green Tortoise trip (that’s all you get to know); the evening on the Green Tortoise farm in Oregon on my first trip with them, in the company of the most beautiful woman who’s ever talked to me; the trip to Covelo with Robert and Ashley, when we spent the whole weekend stoned out of our gourds; taking ecstasy with Ashley at raves; going to certain concerts by bands we loved.

These were all mixed experiences, with all the wash of positive and negative that usually goes on in reality. That great summer at camp was also the only time I ever really hit someone. The night in New Orleans was exciting but also weird and tedious and uncomfortable. The dusk in Oregon triggered my old fear that I’m not helping enough, which back then was probably still true, as we prepped for dinner and later scraped and washed dishes. The weekend in Covelo involved a great deal of heat and boredom. The raves were crowded and noisy and felt great and were exhausting. The concerts were fun and crowded and sweaty and too loud and full of boring breaks and pushing and shoving and distraction.

This doesn’t mean that I can’t remember these episodes positively. They were positive. But I have never been willing to tell myself the truth, which is that nearly every moment in my life has been mixed. Eden is a false dream. Even when I’ve been there, I’ve simultaneously been elsewhere, and only told myself that what felt at the time like boredom and mosquitoes was actually Paradise.

But now here I am, 32 years old, wearing a suit, sitting at a desk in a Manhattan office building, staying sober and trying to accept that I will never fall in love with a beautiful girl in the deep dark woods. This is surprisingly hard to do. I don’t know what to dream instead. I don’t know what to hope for. I don’t know what my goals are, except to stay sober and try to hold my marriage together. There has to be something more than that.

Each day I have been praying to my Higher Power to reveal its will and give me the courage to carry it out. I will keep praying, and I will keep looking, and I will try to live in the present moment. Because ultimately that’s all Paradise has ever been: it’s the moments when I have felt alive and present and connected to the world.

[our wiccan defenders]

I’m not nearly as much of a follower of Wiccan culture and news as I was back when I was dating T, but I’m still pleased to learn that the Wiccan pentacle has been added to the list of approved symbols for government-issue tombstones for fallen soldiers. Religious freedom is a founding principle of our nation, and our soldiers who give their lives in defense of that principle deserve to have it recognized when they are laid to rest. (Via BoingBoing.)

[asking for things]

I just sent my mom an email asking her to send me my Legos, as well as my favorite bear from childhood, Bear Elver, and his wife, Mistress Mouse. Somehow these had also seemed like impossible requests before. Strange how that works.

I feel like I’ve been running from myself since around 12 years old, and I have only stopped running in the last week. It turns out I’m not such an awful person to spend time with. Maybe I can stop running now. Maybe I can get to know me again without the world collapsing.