I know what India’s like. I know because I’ve been there.

That’s how I tend to think, anyway. But do I really have any idea what India is like now? I first went there in 1997, spending four months backpacking alone around the Subcontinent. I returned for another six months in 2002, and then I made a brief, two-week visit for business in 2009.

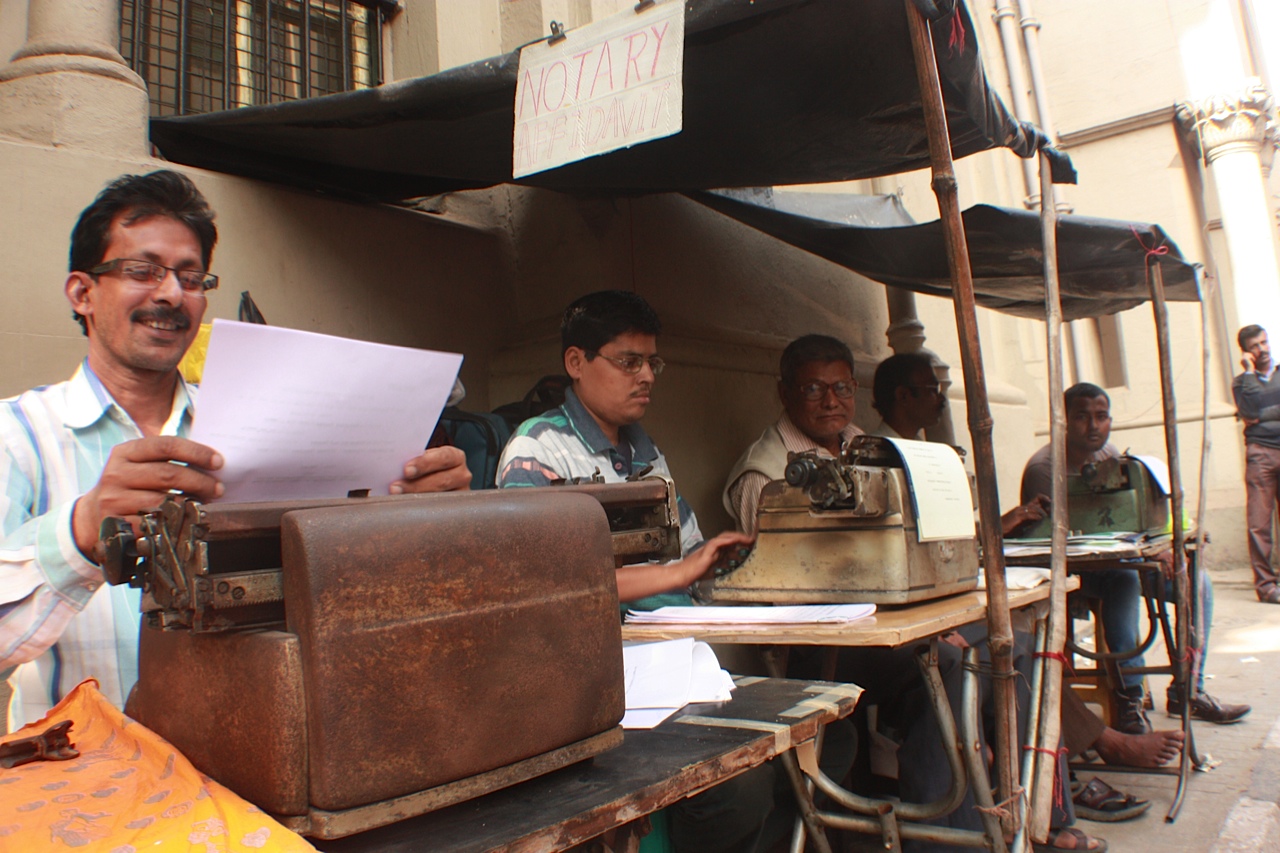

I still describe experiences and memories from that first trip as if that’s just how things are done in India. Yet that trip was 18 years ago. Back then, cassette shops sold music, Internet cafes connected through dialup twice a day to send and receive emails at their own POP addresses, and typists plied their trade (they’re still around, but a dying breed). No one talked about an IT revolution in India — the dot-com boom hadn’t even hit America yet. Business, it seemed, ran on hand-written ledger books. This was the very end of the Congress Party’s long era of dominance: the BJP was running hard, and they won enough seats to form a government under Atal Bihari Vajpayee just a month after I left the country, and the country tested its nuclear weapons a few months later.

Change, in other words, was coming, if you could see the signs. I gathered some sense of the political shift during my travels, but I had no idea about the economic and technological revolution that would transform the country. When I came back in 2002, Internet cafes were everywhere, with uninterrupted power supplies and Internet Explorer 5. CDs had replaced cassettes. Indian Railways was so effectively computerized that a clerk gave me my change when I switched my ticket time and the new one turned out to be cheaper.

I saw further changes when I went back to India in 2009: shopping malls, an emerging security state in the wake of the Bombay attacks, greater ambient wealth. India still felt very much like India, but it wasn’t quite the place I experienced back in 1997.

My frozen home

This frozen-in-time quality is typical of travel accounts — I grew up on my parents’ tales of what Europe was like, as their late-sixties experiences receded ever further back in time — and maybe even more typical of how expats and exiles think of their former homes. It’s funny to me the extent to which parts of Flushing feel more like the Korea of 2001, or even earlier, than like the Korea of today. Restaurants like Kum Gang San cater to Koreans of a certain age, and of a certain Korean era. My parents’ New York City, which they left in the 1970s, is not the New York City I live in.

And very soon, I’ll be talking about a New York City that will be frozen in time.

I’ve been here since 1993, which is quite a while. I’ve seen in change. I’ve called in a dead body in Hell’s Kitchen, and done it on a payphone. I used to go to the 2nd Ave Deli on Second Avenue, and I used to ride the Redbirds out to Jackson Heights for Indian food and not Tibetan food. I remember Pearl Paint and the Twin Towers and the Barnes & Noble on Sixth Ave and the old, hideous Columbus Circle and tokens. A lot has changed.

And it will keep changing without me, after I leave. In a few years, I will be telling someone about New York, and all the hipsters in Bushwick or how Citibike works or how much fun it is to get some ice cream from Chinatown Ice Cream Factory and go to Columbus Park to watch the old men gamble and the old ladies sing, and some actual New Yorker will interject that actually it’s not like that anymore, that they cleaned up the park, changed the bike laws, and moved all the hipsters to Brownsville.

The passage of time

I suppose this is also just a function of getting older. When I was a kid in the eighties, I imagined that the styles then in fashion, music, film, whatever, were just the defaults. I’ve now been around long enough to see things I remembered from the first time come back into style and then go out again. I am aware of the passage of time in a way I couldn’t have been when I was younger.

But then there’s New York. I’ve been here long enough that it’s my home and nowhere else is, but I’m leaving. And New York isn’t a place you can hold onto. It moves on without you. It does not, frankly, give a shit about you, especially if you’ve gone off to live somewhere else. You keep up with New York, not the other way around. Quicker than most places, New York erases and replaces the things you knew.

Well, quicker than most places in America, anyway. Eventually I’ll be settling in Seoul, a city that changes even faster than New York — where you can leave for three years and not be able to find your old neighborhood because the whole thing has been bulldozed and replaced.

And in the meantime? I’ll be traveling, gaining new slices of experience, and trying to remember later when I talk about them to say, “This is how it was then,” instead of “This is how it is.”