A year ago, I embarked on an ambitious Year of No Particular Ambition. Two days ago, I made the least ambitious move of my life. Happy birthday to me.

The unambitious move

Until two days ago, the shortest distance I’d ever moved was across the hall in college, into a vacant double on an air shaft. Now I’ve broken that record by moving into an apartment that was actually adjoining my old apartment, one floor down and one apartment over.

I had to move because the owner of my old place was selling. I didn’t want to go anywhere, and I have managed to achieve that goal pretty spectacularly. The new place has one major advantage, which is that instead of balconies — enclosed spaces, but not heated or cooled, and so unusable much of the year — it just has bigger rooms. Outside of that, it’s basically the same as my old place, right down to the interior fixtures.

Copy/paste

I was anxious before the move, and it took my girlfriend a while to figure out why, until she realized I’d never moved in Korea before. “It’s copy/paste,” she explained. “From your old apartment to your new apartment. Copy/paste.”

And so it was. In New York, two or three Israeli guys would show up, box everything up, and dump it in the new apartment. Here in Seoul, a six-person crew showed up and did stuff American movers can’t do, like unplugging things all by themselves. They refolded my clothes and put them in the closet. They hung curtains. They made the bed. The one woman on the crew — inevitably, she had kitchen duty — cleaned the built-in fridge at the new apartment before restocking it with the food from my old fridge. She also tried mightily to replace my knick-knack shelf exactly as it was, until I told her I’d fiddled with the details later. Then she vacuumed and mopped. Korean movers are efficient and sexist. Copy/paste.

The city gas guy showed up like he was supposed to. The Internet guy, scheduled for a window from two to three, sent a message apologizing for running late and then showed up at 2:30. And then it was done. I’d moved.

Unplanning

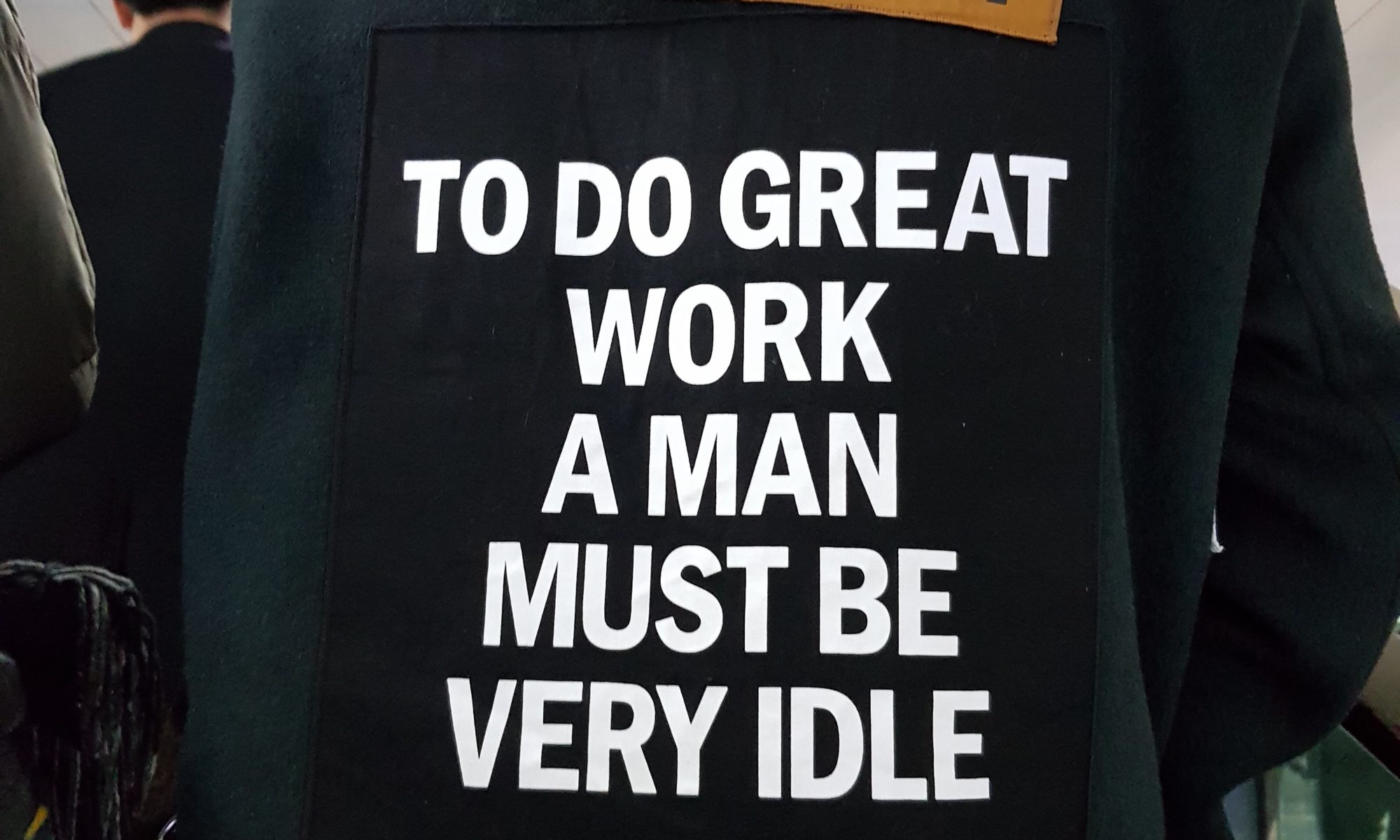

When I’m frustrated or unhappy, I have a habit of retreating into planning: calculating the cost of retiring in Chiang Mai or looking into Ph.D. programs in Busan. It’s the adult version of taking my toys and going home.

When I was actually planning something big — getting a master’s degree, quitting Google, leaving New York, traveling for a year, moving to Seoul — the endless fidgeting with spreadsheets and details had a sense of purpose. Now that I was finally here, it felt more like a tic.

It took maybe half the Year of No Particular Ambition for me to let go of that tic. As the long, cold winter gave way to spring, I felt a change. My parents came for a visit, which gave me a reason to look closely at what’s best and most interesting about my life here so I could share it with them. Partly so I could take them around more easily, I bought a car — a depreciating investment, money spent on now rather than saved for later.

And I fell in love.

Home

For a very long time, all of my relationships have had expiration dates on them: someone is leaving the country, or I just knew it wasn’t something I wanted for the long term.

Then I met Jihyun. We’re two divorced people in our forties, neither of us masters at sticking with relationships, but we’d each been preparing in our own ways. I’d been practicing the art of not running away. Jihyun had been learning how to love by raising her daughter, who’s about four (and delightful). Our relationship has had its ups and downs, but we’ve managed to keep it together for nearly half a year.

A few weeks ago I was at Jihyun’s place, playing with her daughter while she and her mom whipped up a home-cooked dinner of barbecue and and bean paste stew and side dishes. It was special because it wasn’t. I get startled sometimes, in these ordinary moments, at how comfortable I am here. It feels like home.

For this new year, there’s still no grand plan, but I intend to stick with what I’ve got and deepen the roots.

That’s enough.

That’s plenty.