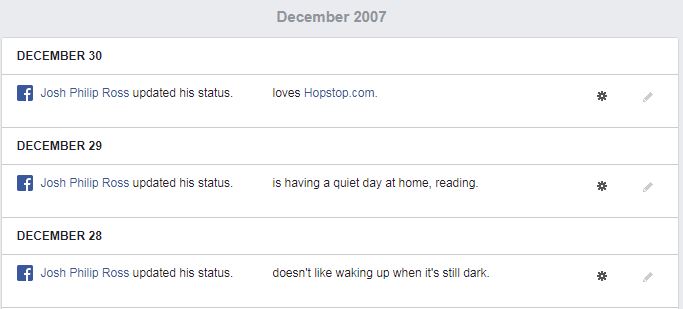

My first Facebook status update, from 2007, was “Josh is going to the Waldorf-Astoria to work on the Foreign Minister’s speech.” Over the next few days, I let people know that I was “tired,” “hungry,” “mildly nervous,” “sorry the 49ers got slaughtered,” and “going swing dancing today.”

That third-person lead-in — remember? — prompted us to write about what was happening to ourselves in the present. This led to a kind of inane self-regard that was easy to make fun of, but it also made Facebook different from a blog, or from Twitter. It was a place to say what you were doing or feeling, not what you were thinking. In November 2008, I made not one political post.

Not dogs

Through all the changes — the end of the lead-in prompt, parents joining, brands joining, Farmville, Upworthy — what stayed interesting was seeing what people we knew, or used to know, were up to in their ordinary lives.

But as Facebook expanded, we became more cautious in what we posted. Silly nattering became vanity and humblebragging. Our online selves became something to curate. On the new Internet, everyone knows if you’re a dog.

More and more, then, we had to show that we weren’t dogs. We had to like and reblog the right things. Facebook became a place to perform our righteous selves. Especially after the election, we pivoted from sharing what we ate or where we went this weekend to sharing what we were outraged about and what we thought you should also be outraged about.

Many of my Facebook friends are legitimately outraged about legitimately outrageous things, but that’s not really a fun place to hang out. Living abroad, I’d hoped to use Facebook to stay in touch with friends back home, but it hasn’t worked out that way. I know a lot about what different people are upset about — trans issues, Democrats who don’t support unions, family separations at the border, guns in schools, Russia’s occupation of Eastern Ukraine, anti-vaxxers — but not what they ate for breakfast and did on the weekend, which is much more interesting.

The great unfollowing

I’m a profligate Facebook friender, but I make up for it by being a pretty ruthless unfollower.

I started years ago, unfollowing anyone who wasn’t an actual person. I’ve unfollowed all the Vietnamese people I friended when I gave lectures in Saigon and Hanoi, and most of the other people I met on my travels. I’ve unfollowed people I’ll never see again: long-gone friends, minor high school acquaintances, ex-colleagues, Landmark contacts. My feed is now down to family, close friends, local friends, news about Korea, and a few people whose posts I find interesting.

This has made my news feed both more interesting and a lot shorter — short enough, by now, that it doesn’t suck me in the way it used to, or at least it shouldn’t. I noticed recently that Facebook was still, out of habit, my go-to activity in moments of boredom, even though it offers less and less.

So I’m consciously trying to change that. I used to make sure never to leave the house without a book or The New Yorker, two if I was getting towards the back of the first one. I have all that on my phone, and I’m training myself to go there first. Facebook can wait.