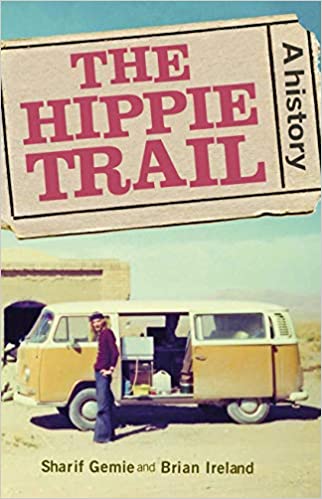

Sharif Gemie and Brian Ireland, The Hippie Trail: A History (2017)

This is an odd little book. It appears to be the first attempt to write the history of what was known as the Hippie Trail, or the Hashish Trail: the overland route from Europe to India that began around 1957 and ended in 1978. (The boundaries are set, at the beginning, by the first overland coach service from England, at first used mostly by Indian nationals, and also the publication of Kerouac’s On The Road, and at the end by the Iranian Revolution and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.)

Part of what’s so odd is that this is the first, and as far as I can tell, the only history of a phenomenon that swept up hundreds of thousands of travelers, made its way into popular songs by everyone from Janis Joplin to Bob Seger to Rush, was covered extensively and often luridly in the press, yet seems never to have generated any professionally written books at all beyond a couple of sensationalistic novels. The countless memoirs produced by travelers have been largely self-published or circulated in manuscript. This is all the stranger when you consider the success of so much adjacent writing: Gita Mehta’s Karma Cola, which picks apart the hippie guru culture of Western travelers to India in the seventies; Pico Iyer’s Video Night in Kathmandu from a few years later looking at how Western culture has come to pervade the East; or even Remember, Be Here Now, Ram Dass’s personal story of spiritual transformation in Nepal and India.

Gemie and Sharif make an honorable if not quite comprehensive effort, having found eighty-eight Hippie Trail travelers to interview, as well as having slogged through a mountain of poorly written, poorly edited memoirs. There are times when their efforts feel a little amateurish, but I suppose that’s to be expected from scholars wading into territory no one else has bothered with. This is not the kind of book anyone should read who doesn’t have a personal or academic interest in the Hippie Trail, but it makes a decent case that more people should have the latter.

From my perspective, I most wanted to understand how and why travelers came to choose this route, this destination. In delving into it, Gemie and Ireland find that a search for drugs or a spiritual quest were the most common reasons given, when the reason was anything more articulate than just a vague quest for adventure or the exotic. But why India for all that? Indeed, it seems that in the early days, Morocco played much the same role for drugs and exotic adventure, but not for the spiritual quests as much. I suppose it may be asking too much of this book to look for the deeper roots of the fascination with India, and I have others for that.