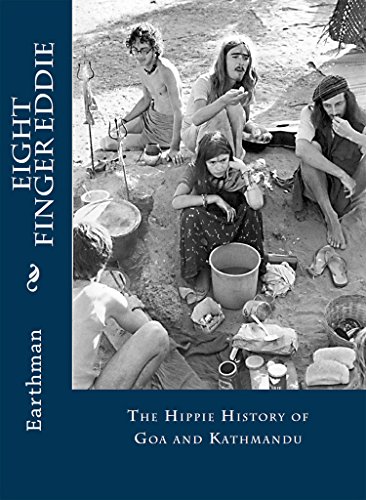

Earthman, Eight Finger Eddie: The Hippie History of Goa and Kathmandu (2015)

This is a terrible book. I mean, really terrible. Written by someone who calls himself Earthman and self-published on Amazon for a buck ninety-nine (I mock, but is it where I end up?), Eight Finger Eddie is a sloppy mess of a book that attempts to tell the life story of Yetward Mazamanian, a local hippie hero known as Eight-Finger Eddie (he was born with just eight fingers) who was one of the first freaks to settle in Goa, and who, by virtue of being a couple of decades older than everyone else and pretty chill, turned into a kind of father figure to a lot of the lost, confused hippies who wandered in. (Earthman was one of them.)

The terribleness of this book is not just in its poor editing, its endless repetitions and recaps, or its lack of research — Earthman seems to have relied entirely on Eddie’s recollections, without checking anything — but in the adolescent, retrograde attitudes of its author, who seems never to have outgrown the viewpoints of the stoned kid he was when he first visited Goa in the early seventies.

But that’s what makes this book so useful.

I remember Goa as the one place in India that still felt colonized. The Westerners treated it like their own, and they treated the Indians as a nuisance to be dealt with. The locals don’t like nudity? Fuck ’em. The locals want to build a resort? How dare they ruin my dirt cheap paradise for their own financial gain!

Over the course of this book, Earthman manages to engage in an astonishing range of colonialist hippie cliches. He describes women as “luscious” again and again. When Eddie’s white girlfriend has engaged in a threesome with a couple of Mexican villagers, Earthman declares that the two of them “have made contact with the natives — way beyond National Geographic!” He goes into a tizzy when he feels Eddie’s wild experiences have trumped his own freakiness. He declares himself “deeply fascinated by India” and thinks there’s “pure village life” out there, but never makes any particular effort to engage with it beyond hippie hangouts in Goa.

At one point, bitching about Panjim’s big city ways, Earthman takes a leak on some public shrubbery, without grasping that this is what the hippies have been doing to Goa for decades. The pristine beaches they found back in 1971 weren’t pristine anymore once they had hippies camping, pissing, and shitting all over them. It never seems to occur to him that the tourist development of Goa he so despises — the charter flights, the resorts, the cops hassling the druggies — might be a boon to the Goans, whose state boasts some of the highest income and social indicators in India.

And these selfsame Goans, whose tolerance gets mentioned a lot, may have reasonably become exhausted with the insanity the hippies brought. It takes Earthman a long time to get to it, but his story finally winds around to Goa in the seventies, and to the various hippie houses Eddie led. They were places where people could, and did, go totally insane. Jumping down wells in fits of pique seems to have been a common behavior. Bursts of violence were not unusual. And then, when the wells began to run dry as the hot season approached (never would Earthman wonder who used up all the water), the hippies split, heading for Kathmandu while the locals had to go on living on their meager wages in Goa.

I remember that atmosphere of impending violence in Goa, something I felt nowhere else in India or Nepal. I thought it was because it was late in the season, with only the most exhausted burnout cases still hanging around. Or maybe, I thought, it was because so many people were waiting for the start of a party that had ended years earlier. But maybe that was just what Goa was about: the place the crazies went, and only the crazies stayed, because it was crazy — a kind of permanent colony for the Acid Test crowd. I grew up in the aftermath of the great hippie dream, and I saw many sides of it, good and bad — macrame and Volvos at the food co-op, lots of stoned parents, barefoot kids running around Point Reyes Station, crystal shops and bearded mystics, people trying to convince me carob was the same thing as chocolate — and Goa seemed to be the worst of the worst. And Earthman, in his obliviousness, has done much to confirm my impressions.