“A life is like a garden. Perfect moments can be had, but not preserved, except in memory. LLAP”

Odd eye

Money for love

McDonald’s wanted you to demonstrate love in order to receive food. Coke fantasized that it could overcome hate through a Coke-based industrial accident. And now Dove is telling women to shut up already about their bodies (through a Twitter campaign that replies to women’s negative posts about their bodies with messages that are supposed to be empowering or positive).

These campaigns are part of an ugly trend in advertising. It’s troubling is when brands want to be my leader, my friend, my moral compass.That’s not OK. I would like to be able to drink a cup of tea without receiving an exhortation, for example.

Brands, corporations, and people

We all know that giant corporations like Facebook and Google (yes, the hand that feeds me) have more information than they ever did about our daily habits, thoughts, desires, interactions. It’s astonishing, when you think about it, just how much you could gather from my mobile phone data, Google searches, and Facebook feed. And we all know that these giant corporations sell that data to advertisers and marketers. And I’m actually pretty OK with all that: advertising has been a part of my world for my entire life, and I’d rather see ads that are relevant to me than just random garbage scattered across the televisual landscape. Done right, advertising can actually be useful, like an airline recognizing that I’m searching for flights to a particular city and deciding to give me a discount to entice me to go with them. They win, I win. It’s fine.

Brands are owned by corporations, and corporations are organizations designed to make profits, not to improve your moral worth. As such, they lack the disinterested moral authority of clergy (pledged to a religious responsibility), therapists (licensed and beholden to professional ethics), or friends and family (people we’ve decided for our own reasons to trust). Moral exhortations from corporations are a confidence game.

Now it’s worth remembering that, as Mitt Romney had it, corporations are people, or at least made out of people (like Soylent Green). Marketing campaigns do not create themselves. Corporate leaders can and often do desire to do good in a broader sense than simply making profits. That kind of leadership is good and should be encouraged. Companies that provide great service or go green or treat their employees well deserve accolades.

Do as I say, not as I sell

But as with people, there’s a difference between companies that do good and companies that talk about doing good. Dove is the latter. So is McDonald’s. That’s what rankles, the way it would rankle to have some rich guy fly in on a private jet, ride his souped-up Harley over to your shitty little house, and remind you how important it is to be humble and leave only footprints.

To a great extent, these campaigns have consisted of corporations wrong-footing themselves in a complicated Internet landscape that they don’t quite know how to handle. Because we have the Internet, we can talk back, and people are doing just that. I suspect that the current trend of earnest moral exhortation as brand message will not last — not if it keeps pissing people off.

Money for love

McDonald’s wanted you to demonstrate love in order to receive food. Coke fantasized that it could overcome hate through a Coke-based industrial accident. And now Dove is telling women to shut up already about their bodies (through a Twitter campaign that replies to women’s negative posts about their bodies with messages that are supposed to be empowering or positive).

These campaigns are part of an ugly trend in advertising. It’s troubling is when brands want to be my leader, my friend, my moral compass.That’s not OK. I would like to be able to drink a cup of tea without receiving an exhortation, for example.

Brands, corporations, and people

We all know that giant corporations like Facebook and Google (yes, the hand that feeds me) have more information than they ever did about our daily habits, thoughts, desires, interactions. It’s astonishing, when you think about it, just how much you could gather from my mobile phone data, Google searches, and Facebook feed. And we all know that these giant corporations sell that data to advertisers and marketers. And I’m actually pretty OK with all that: advertising has been a part of my world for my entire life, and I’d rather see ads that are relevant to me than just random garbage scattered across the televisual landscape. Done right, advertising can actually be useful, like an airline recognizing that I’m searching for flights to a particular city and deciding to give me a discount to entice me to go with them. They win, I win. It’s fine.

Brands are owned by corporations, and corporations are organizations designed to make profits, not to improve your moral worth. As such, they lack the disinterested moral authority of clergy (pledged to a religious responsibility), therapists (licensed and beholden to professional ethics), or friends and family (people we’ve decided for our own reasons to trust). Moral exhortations from corporations are a confidence game.

Now it’s worth remembering that, as Mitt Romney had it, corporations are people, or at least made out of people (like Soylent Green). Marketing campaigns do not create themselves. Corporate leaders can and often do desire to do good in a broader sense than simply making profits. That kind of leadership is good and should be encouraged. Companies that provide great service or go green or treat their employees well deserve accolades.

Do as I say, not as I sell

But as with people, there’s a difference between companies that do good and companies that talk about doing good. Dove is the latter. So is McDonald’s. That’s what rankles, the way it would rankle to have some rich guy fly in on a private jet, ride his souped-up Harley over to your shitty little house, and remind you how important it is to be humble and leave only footprints.

To a great extent, these campaigns have consisted of corporations wrong-footing themselves in a complicated Internet landscape that they don’t quite know how to handle. Because we have the Internet, we can talk back, and people are doing just that. I suspect that the current trend of earnest moral exhortation as brand message will not last — not if it keeps pissing people off.

Goals

“Beware of looking for goals: look for a way of life. Decide how you want to live and then see what you can do to make a living WITHIN that way of life.” — Hunter S. Thompson

PMS

February

“Why does February only have 28 days? Because no one could stand any more.” — Mom (and yeah, it was 8 degrees this morning)

Korean fusion

Korean fusion

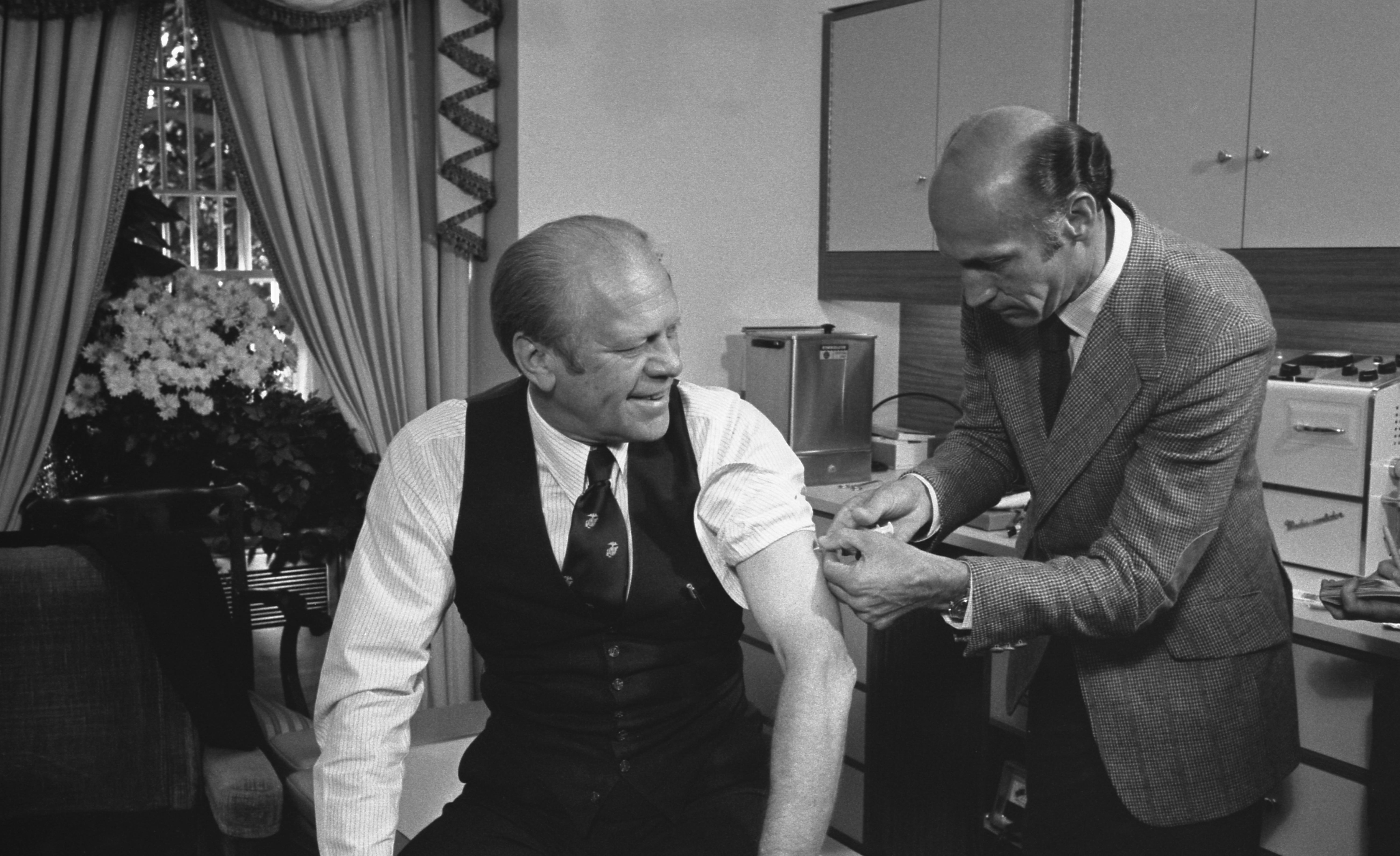

Vaccines and time

Remember the scare about EMFs? Remember Satanic ritual abuse? Remember how cell phones were going to give us brain cancer? The list of things we’ve been afraid of is long, but it changes over time.

That’s something to keep in mind as you consider the current dangerous anti-vaccine movement. Because these scares have no basis in fact, they’re not sticky. They’re fashion trends, and things go in and out of fashion. In particular, it’s worth noting that the anti-vaxx crowd consists of people who like to think they’re smarter than everyone else: lefty liberals, Northern Californians, Silicon Valley tech workers. Once your marvelous insight is shared by the great unwashed masses, it’s time to move on to something else.

Vaccines present an unusual problem because the panic has a meaningful way of manifesting: parents refuse to vaccinate their children. This is different from simply being freaked out about power lines or mobile phones. Nevertheless, I do think there’s some hope that this anti-vaccine trend will taper off with time — especially (alas!) after some children begin to die.

A worrying counter-trend is food fears, which do tend to last: people are still insisting on the dangers of aspartame and MSG and gluten long after the initial studies showing problems with these ingredients were overturned by better studies. I think that’s because of the ritual, almost spiritual quality of food in human life, and I hope that’s the case; if it’s more an issue of being afraid about what we put in our bodies, then the anti-vaccine problem might be stickier than I’m predicting.

Nevertheless, I do think there may be some possibility that the anti-vaccine epidemic, like so many earlier epidemics, will run its course with time. Hopefully we can inoculate ourselves against a recurrence.