Myanmar is where Asian buses go when they die. You see them trundling down Yangon’s avenues, exposed engines belching, the Korean or Japanese or Chinese route destinations sometimes still visible. I began to think of Yangon as a sort of Buddhist hell realm for buses, like the bottom wedge of a Tibetan thanka painting, where they’re reincarnated as flayed beasts that have to pay for the sins of their past lives. At moments, too, I had the weird fleeting hope that I could hop on one of these buses and leave behind the dusty, crumbling chaos of Yangon for, say, Shinchon Station in downtown Seoul.

Myanmar was daunting. Internet connections were hinky and slow. There’s not yet much of a backpacker scene, travel options are limited, food can be terrible, roads are bad, English speakers are scarce. It was by far the most difficult place I’ve traveled on this trip, though I don’t want to exaggerate the hardship either: I stayed in hotels, rode in VIP buses, went to tourist sites where I met other travelers. Still, everything’s a little trickier and more arduous in Myanmar: getting on a VIP bus means riding for a half-hour in the back of an open truck to get to the VIP bus; staying in a hotel by the airport still results in a half-hour taxi ride over rough roads to get the airport four kilometers away.

And some of what made Myanmar feel like a slog was how I approached it. I was on the move more than I had been in other countries: before Myanmar, I was averaging close to four days per location; in Myanmar, it was more like two days. But also, the travel was physically harder: a three-day, two-night trek that meant a couple of freezing cold homestays on hard floors; an overnight bus; some very uncomfortable minivan rides. By the time I reached the end, I was exhausted and ready to leave.

Filipinos in the synagogue

The heart of Yangon, along the river, is a dense grid of mostly old colonial buildings from the turn of the 20th century. Like Cuba, Myanmar has spent a long time cut off from global capital, resulting in a kind of accidental preservationism, though the old buildings are mostly in terrible shape. There’s a dearth of basic modern conveniences like grocery stores. Done right, Yangon could transform itself into a UNESCO World Heritage city like Melaka and George Town in Malaysia or Hoi An in Vietnam, but on a grander scale. Done wrong, and in ten years Old Yangon will be nothing but cheap, shitty glass boxes and a faint memory of what was and what could have been.

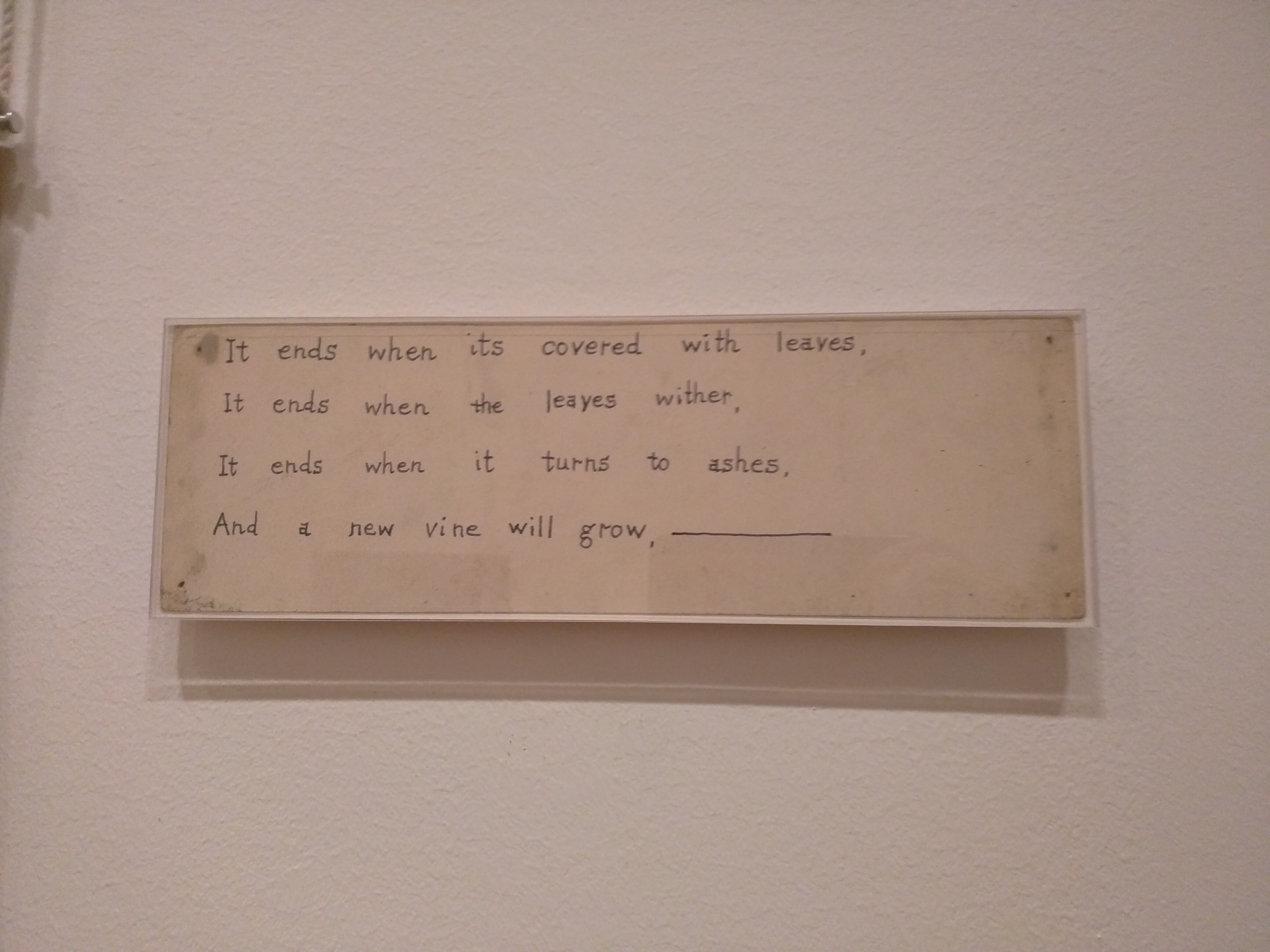

You could feel, walking around, that Myanmar is changing. There are cell phone shops everywhere. Art galleries have sprung up, with explicitly political paintings; one artist cuts up old Myanmar money to make collage portraits of Aung San Suu Kyi. You see posters for Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy in shops, too, and books about her in the book stalls. I was in Myanmar after the election in which the NLD took about 80 percent of the vote, but before they took over parliament at the beginning of this month. You could feel that hopes were running high, though tempered by a long history of disappointment.

I went to the pagodas you’re supposed to go to, and they were OK, though not as beautiful as Thailand’s major temples. What was best in Yangon was the street life. On my second night in town, in one of the open-air barbecue restaurants on 19th Street, I met some expat Filipinos and one Burmese friend of theirs, and we had sort of a party at the table with whoever else happened to sit down beside us. The next night, I took the whole crew to the local synagogue, which has been kept open all through the years by the Samuels family. It was Friday night, and I ended up leading the prayer services for the few Jews there: a photographer, an Australian family, and a Samuels daughter. The Filipinos had never seen a Jewish ritual before, and they applauded after each bit that I sang.

We were all supposed to go out clubbing, but the stomach troubles that had been plaguing me since Malaysia now took a turn for the worse. My new local friends were kind and helpful, taking me to a pharmacy before sending me back to my hotel. It was a long night, and the next day’s trip to Bagan, I knew, wouldn’t be easy.