After a wet, blustery Saturday, it was a pleasure to step out into the crisp, clear air on Sunday for the second half of the Annual Gowanus Artists Studio Tour (AGAST) (see my account of day one below). This time I was joined by my wife Jenny, and our first stop was the group show at location #23, on 9th St. between the Gowanus Canal and 2nd Avenue. In this maze of a building, which one viewer described as first-person-shooter-like, were over a dozen studios, as well as work collected from artists showing at different locations, making #23 AGAST’s Magical Mystery Tour. It was also at #23 that we bumped into my friend Daniel — my companion on day one — and his fiance Sally, the two of whom joined us for the rest of our ramble through Gowanusy goodness.

I couldn’t possibly do justice to all of the artists at #23, but I’d like to mention as many as I can.  Geoff Grogan (who was dressed, appropriately, in a Superman T-shirt) ingeniously constructs oversized comics tableax from shredded bits of the New York Times, pulling apart newsprint to recreate a newsprint form. The obvious comparison is to Roy Liechtenstein, but where Liechtenstein hides his brushstrokes to create a cold, distancing modernist sheen, Grogan’s collages feel immediate and warm, recalling the intimacy of a comic book read by flashlight under the covers. Grogan is also the author of Dr. Speck’s Comics.

Geoff Grogan (who was dressed, appropriately, in a Superman T-shirt) ingeniously constructs oversized comics tableax from shredded bits of the New York Times, pulling apart newsprint to recreate a newsprint form. The obvious comparison is to Roy Liechtenstein, but where Liechtenstein hides his brushstrokes to create a cold, distancing modernist sheen, Grogan’s collages feel immediate and warm, recalling the intimacy of a comic book read by flashlight under the covers. Grogan is also the author of Dr. Speck’s Comics.

The “assembled worlds” of Joshua Marks were another highlight. Constructed of photographs and figurines in tiny lighted boxes, they feel like windows onto a strange alternate world. In contrast to these jewelbox creations was what Marks called “My Albuquerque,” a vast plateau of cracked earth punctuated by small slices of suburbia — model houses, plastic grass — under plastic domes. He declared that he would sell it at cost to anyone who had a place to put it, but at approximately 20 feet square, this horizontal work is likely to stay put for a while.

Olivia Valentine takes photographs of Avon perfume bottles that she collects, as well as large prints of photographs of her grandmother’s old porcelain figurines, and others she collected herself, to surprisingly creepy effect. Julia Simon’s entertaining horror-show included a big, campy Count-like vampire mounted on the wall, with fangs that dispensed vodka-spiked cranberry juice. (In a subsequent email, I was informed that he has since been dubbed “Count Drunkula,” and that the artist’s boyfriend, Erik Burns, helped out in the creation of the drink-dispensing demon.)

The dark emotion was palpable in Jessica Brommer’s paintings of distorted faces and ghostly montages, and in her wall-mounted sculptures of dessicated pelicans. Kimi Weart’s drawings were also unsettling, with images of animals retaking the human world. In one large piece, dear have taken over a rural parking lot, fighting and standing about in far greater numbers than the station wagons scattered about. In another, a wolf seems to vomit some kind of white glitter. Jim McGrath’s fine paintings of giant worms against backgrounds of half-hidden words on Hiroshima and other subjects were similarly eerie. Conceptual artist and sculptor Saul Melman’s gallery was largely filled by two big mobiles of tangled cardboard strips, but what drew people’s attention was a cake encrusted with dust and grime. (Update: The artist has explained to me that the cake is in fact covered with dust from September 11, 2001, and was recently included in a group show of art relating to 9/11. The work now strikes me as an apt illustration for what that period felt like: the horror of 9/11 making us choke on the good times of the late 1990s.)

More cheerful were the assemblages of Tamara Thomsen, which included a sort of playground for abstract stuffed kittens and a wooden fence on which were impaled a score or so gourds. I enjoyed the lush bodies in motion of Elsie Kagan, the Klimt-like work of Scott Facheux, and especially the spare, poignant paintings of Astrid Cravens (pictured), constructed of tiny dots against wintry fields of shifting color.

More cheerful were the assemblages of Tamara Thomsen, which included a sort of playground for abstract stuffed kittens and a wooden fence on which were impaled a score or so gourds. I enjoyed the lush bodies in motion of Elsie Kagan, the Klimt-like work of Scott Facheux, and especially the spare, poignant paintings of Astrid Cravens (pictured), constructed of tiny dots against wintry fields of shifting color.

Other artists included Cynthia Winings, Annie Leist, Monique Davidson (who made blankets and clothes for babies), Katie Padden, Linda Tharp and Francis Sills.

Up on 3rd Ave. between 6th and 7th streets, we came to #24 on the tour — home of Third Avenue Clay — where we entered a second-floor gallery rich with incense and reggae sounds. The space was shared by Areta Buk and Abbyssinian Carto. Abbyssinian was the fellow with the dreadlocks, and his intricate paintings of hands and symbols that made me think of the Mithali paintings of northern India. Buk’s paintings were complex and precise. The rest of the building was taken up with the pottery of Orla Dunstan and Adrienne Yurick and the whimsical ceramic sculpture of Geri Gventer.

Moving over to 4th Ave., we were struck by all the new construction: signs of the changes afoot now that 4th Ave. has been rezoned for high-density residential development. It’s still a wasteland for foot travel, with its gas stations and vast taxi dispatchery. There was also, deep inside one of the inscrutable enclosures along the Gowanus, what looked like a pigeon coop. I can only hope it was not someone’s food source.

On 2nd Street we came to #25, our first home of the day, where we saw the flower paintings (and extensive tie collection) of Bill Thibodeau in his densely packed studio. Buried in a corner was a sort of cartoony Madonna and Child.

From there we crossed to 5th Ave., and suddenly we were well beyond the Gowanus zone and into the gentrified realm of Park Slope. On the top floor of an elegant home on Carrol St. (#26), we saw the drawings and paintings of Elizabeth Reagh. My friend Sally was particularly impressed with her sketches of her baby (now an older boy, shown in a later drawing slumping miserably in his chair), while I enjoyed her Brooklyn landscapes, particularly one with a vivid orange sky. In the background we could hear her dryer going. I also enjoyed her homemade chocolate-chip cookies.

Next up was #11, the shared studio of Elinor Dei Tos Pironti, whose abstract paintings explore color overlays in plaid formations; sculptor and potter Myrna Gordon, whose strange hanging tosos and arms and masks look like skin that has been peeled away (pictured); and stone sculptor Rosalind Kochman, who creates abstract works in marble and alabaster.

Next up was #11, the shared studio of Elinor Dei Tos Pironti, whose abstract paintings explore color overlays in plaid formations; sculptor and potter Myrna Gordon, whose strange hanging tosos and arms and masks look like skin that has been peeled away (pictured); and stone sculptor Rosalind Kochman, who creates abstract works in marble and alabaster.

The next studio, Gallery 718 (#10), was the only one housed in a proper storefront, on busy 5th Ave., and  it clearly functions as a commercial art gallery, which gave it a very different feel from the other studios we’d visited. We saw the work of Elizabeth Eckman and Alissa Neglia, but the space was dominated by the witty canvases of David Vigon. I was particularly struck by his “Smirky Boy” (pictured) and by a painting of a cityscape in black and white, with two helicopters, one in pink and the other in lime.

it clearly functions as a commercial art gallery, which gave it a very different feel from the other studios we’d visited. We saw the work of Elizabeth Eckman and Alissa Neglia, but the space was dominated by the witty canvases of David Vigon. I was particularly struck by his “Smirky Boy” (pictured) and by a painting of a cityscape in black and white, with two helicopters, one in pink and the other in lime.

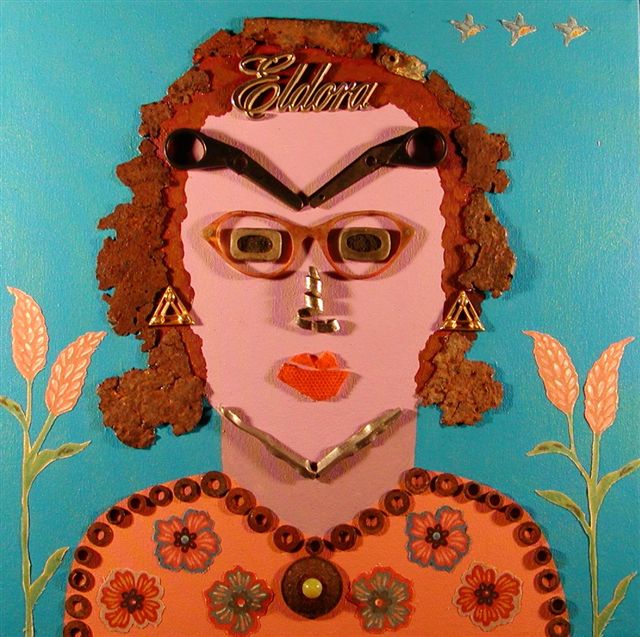

By this time I could stand it no longer. We had notions of taking some other route, but I insisted that we go straight to #9, the studio of Elyse Taylor, who was and remains my favorite artist on the Gowanus Tour. Climbing up the stairs to her studio, I was delighted to see again her pink neon RETRO sign, and then to turn a corner and find myself face to face with her extraordinary multipanel work “Growing,” which had indeed grown since I last saw it. Taylor’s imagination seems bottomless as she produces panel after panel of witty, precisely executed additions to this fascinating work. She was also showing a wide variety of paintings and drawings that shifted style and genre yet all somehow had the Taylor touch.

There is something about Elyse Taylor’s work that makes people smile,  but there is nothing toothless or polyanna about her work: another couple was in the studio with us was cooing delightedly at the painting of the one fellow choking the other fellow, and then the woman let out a cheerful giggle at the painting of the green-faced man sniffing glue. Somewhere in “Growing” is a Buddha, and Taylor’s approach to art and life strikes me as fitting well with a Buddhist outlook, in which the dark and scary parts of life are neither something to run from nor something to dwell upon overmuch, but rather just aspects of the complexly interesting fabric of reality. And Taylor is certainly a deeply curious person (in both senses, in the best way), constantly exploring new uses of found materials and coming up with clever new jokes to work into her art.

but there is nothing toothless or polyanna about her work: another couple was in the studio with us was cooing delightedly at the painting of the one fellow choking the other fellow, and then the woman let out a cheerful giggle at the painting of the green-faced man sniffing glue. Somewhere in “Growing” is a Buddha, and Taylor’s approach to art and life strikes me as fitting well with a Buddhist outlook, in which the dark and scary parts of life are neither something to run from nor something to dwell upon overmuch, but rather just aspects of the complexly interesting fabric of reality. And Taylor is certainly a deeply curious person (in both senses, in the best way), constantly exploring new uses of found materials and coming up with clever new jokes to work into her art.

Another thing I love about Elyse Taylor is that she sells art for cheap. I don’t have the sort of income one needs to be a serious collector of art, but at this point I have six original Taylors, which cost me a grand total of $105.  To add to the painting of a television that I bought last year (similar paintings were still available for $15), I bought a marvelous red square canvas with a red computer keyboard button labeled “PANIC” affixed to the center ($20); a square over which a button-down shirt had been stretched like a canvas after it was stamped over and over in red with what is supposedly the artist’s name in Chinese ($40); an oddly shaped painting of a broken-down school bus daubed with graffiti ($20); and two small line drawings ($5 each). Our collection of original Taylors now has pride of place above our bed.

To add to the painting of a television that I bought last year (similar paintings were still available for $15), I bought a marvelous red square canvas with a red computer keyboard button labeled “PANIC” affixed to the center ($20); a square over which a button-down shirt had been stretched like a canvas after it was stamped over and over in red with what is supposedly the artist’s name in Chinese ($40); an oddly shaped painting of a broken-down school bus daubed with graffiti ($20); and two small line drawings ($5 each). Our collection of original Taylors now has pride of place above our bed.

In any case, I urge you to visit Ms. Taylor and not wait until next year’s AGAST to do it. She’s a very nice woman, and I would say that her personality is as good as her art, but it’s not: the world has lots of nice people but very few artists this interesting. Give her a call and go. She’ll be happy to see you, and you’ll be happy to see her.

The sun was low in the sky by the time we left Taylor’s studio, and it was clear that I was going to  fall short of my goal of hitting every studio on the tour like I did last year. It was also at around this point that Sally coined the term “Artditarod” for what we were doing. Meanwhile, Daniel had a particular favorite artist over at #16, one Jennifer Bevill, so we swung back toward the Gowanus to 543 Union Street, at Nevins, an old warehouse with many studios inside. Ascending to the top level, past a giant safe, we took a detour to the roof, which afforded us beautiful views in all directions of Brooklyn’s rooftops and church spires, the thick cumulous clouds glowing in the slanting evening light. Then it was back downstairs to Bevill’s fascinating story-quilts (pictured) and tempting little packages, which seem to carry all of American folk history in them. I was also fond of her book Painted Shut: An Anthology of Art Traumas, which consisted of short passages of real people telling stories of disastrous experiences with art (for example, an educator being told at a seminar to teach his kids to paint with “happy colors”), coupled with illustrations by Bevill.

fall short of my goal of hitting every studio on the tour like I did last year. It was also at around this point that Sally coined the term “Artditarod” for what we were doing. Meanwhile, Daniel had a particular favorite artist over at #16, one Jennifer Bevill, so we swung back toward the Gowanus to 543 Union Street, at Nevins, an old warehouse with many studios inside. Ascending to the top level, past a giant safe, we took a detour to the roof, which afforded us beautiful views in all directions of Brooklyn’s rooftops and church spires, the thick cumulous clouds glowing in the slanting evening light. Then it was back downstairs to Bevill’s fascinating story-quilts (pictured) and tempting little packages, which seem to carry all of American folk history in them. I was also fond of her book Painted Shut: An Anthology of Art Traumas, which consisted of short passages of real people telling stories of disastrous experiences with art (for example, an educator being told at a seminar to teach his kids to paint with “happy colors”), coupled with illustrations by Bevill.

In the next room over, we found the installation work of Kenan Juska, who collects the fabulous junk to be found in New York — abandoned cassette tapes, matchbooks, advertisements, cans, electronic bits and pieces — and assembles it into compelling collages. I was reminded of something I realized while exploring the art scene in Korea: New York has really great junk. This kind of scrap art is something we simply never saw in Korea, probably because they’ve got a lot fewer scraps lying around than we do, having been bombed to smithereens some 50 years back. And then there’s Italy, which had such exquisite junk buried about the place that it served to launch an entire cultural rebirth. I suppose my point is that the quality of the local junk has perhaps an underrated influence on a region’s art.

Another unusual studio was that of stained-glass artist Ernest Porcelli, where you could see stained glass in every phase of its development, from the numbered sketches that show where each pane will go, to the raw glass in various colors and textures, to pieces that have begun to be laid out, to finished works with the seams filled in.

Elizabeth O’Reilly does paintings of the Gowanus area (pictured), while Joanne McFarland paints exquisitely realized Brooklyn brownstones. The drawings of Joanne Pasila, who recently moved to the city from rural Massachussets, seem to have absorbed the urban rhythms of her new environment.

Elizabeth O’Reilly does paintings of the Gowanus area (pictured), while Joanne McFarland paints exquisitely realized Brooklyn brownstones. The drawings of Joanne Pasila, who recently moved to the city from rural Massachussets, seem to have absorbed the urban rhythms of her new environment.

Carla Roley showed elegant photographs of Vietnam and the Western United States. I was charmed by Joelle Shallon’s colorful abstract paintings in unusual shapes. Other artists included Robin Feld, Leslie Kushner, Marion Lerner-Levine and Margaret Neill.

By now time was running short, and I wanted to see the studio of Melanie Fischer, which in past years had been turned into fantastic environments (something similar is pictured). When you look at the tour map, #14 looks like it’s right in the heart of the densest section, but the blocks on either side are empty and windblown, so Fischer and her collaborator this year, Anita Welsh, liberally decorated the sidewalks with big chalk arrows, admonitions to keep going, an “ALMOST THERE,” and even a few ellipses to get travelers through the tough patches. Upon arrival, we were welcomed by an elaborately crayoned staircase that led to Fischer’s long, narrow, skylit studio. The work on display was mostly from last year, with a couple of exceptions. First of all, there was Welsh’s contribution of scrub brushes in which the bristles had been replaced by crayons, and which had been used to decorate a section of floor. She’d also melted down crayons and made them into soap bars, presumably for uncleaning purposes. The other new work, six months old and still in progress, was Fischer’s baby, which has understandably distracted her from the important but time-consuming work of, say, filling her studio with dirt, like she did last year.

By now time was running short, and I wanted to see the studio of Melanie Fischer, which in past years had been turned into fantastic environments (something similar is pictured). When you look at the tour map, #14 looks like it’s right in the heart of the densest section, but the blocks on either side are empty and windblown, so Fischer and her collaborator this year, Anita Welsh, liberally decorated the sidewalks with big chalk arrows, admonitions to keep going, an “ALMOST THERE,” and even a few ellipses to get travelers through the tough patches. Upon arrival, we were welcomed by an elaborately crayoned staircase that led to Fischer’s long, narrow, skylit studio. The work on display was mostly from last year, with a couple of exceptions. First of all, there was Welsh’s contribution of scrub brushes in which the bristles had been replaced by crayons, and which had been used to decorate a section of floor. She’d also melted down crayons and made them into soap bars, presumably for uncleaning purposes. The other new work, six months old and still in progress, was Fischer’s baby, which has understandably distracted her from the important but time-consuming work of, say, filling her studio with dirt, like she did last year.

When we left Fischer it was after six o’clock — past closing time — but as we headed back toward Nevins St., we spotted an open door and decided to head on in. Some of the artists at #15 were packing up already, but they graciously allowed us to wander through and see what there was to see. I remembered a number of them from last year, including Felicity Faulkner, who was busily wrapping up her paintings when we entered. When she saw my notebook, she suggested I describe her paintings (pictured) as “strong optical work” and added that that’s what everyone says. Nor is she wrong about that, so I’ll let it stand. She also told me I could describe her as a “charming English lady.”

Tucked into a corner, in a room painted a bright pastel pumpkin, were the Hindu-inspired collages of yoga teacher Esther Jyoti Larson. I also greatly enjoyed the sculptures and photographs of Jim Gratson, who constructed Chinese characters out of wood blocks and whose photos included pictures of a bundled-up kid half-buried in snow as he makes snow angels and another series of a little girl under water in a swimming pool.

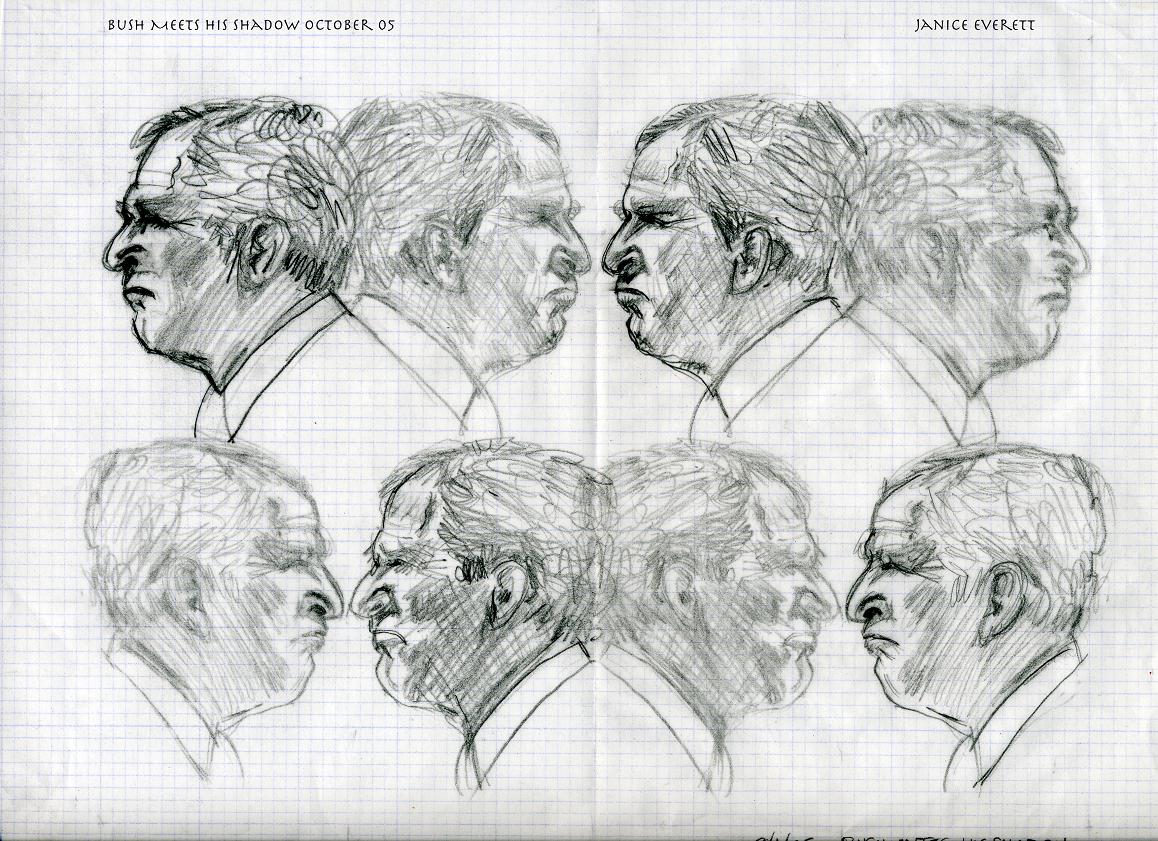

Also unduly impressed by my notebook was Janice Everett, another charming English lady who did mostly design-oriented drawings in black and white (and who I happen to find totally hot, even though she’s probably 20 years my senior). “Are you press?” she asked me. “You look very official.”  When I told her that I was merely a blogger, I found myself surrounded by several people my parents’ age who sought knowledge at the font of computer wisdom. “How do I find blogs?” “Can I leave my laptop on all the time?” Then, as I was about to go, Everett asked me excitedly if I had seen her bush drawings, and it took me a moment to realize that she meant her Bush drawings (pictured), a series of the president looking sour in the aftermath of Katrina, entitled “Bush and His Shadow.” So I gave them a look, and then we were on our way, done with the Annual Gowanus Artists Studio Tour for another year, and headed over to Cafe Mexicano for hot chocolate and excellent Mexican dinners for cheap.

When I told her that I was merely a blogger, I found myself surrounded by several people my parents’ age who sought knowledge at the font of computer wisdom. “How do I find blogs?” “Can I leave my laptop on all the time?” Then, as I was about to go, Everett asked me excitedly if I had seen her bush drawings, and it took me a moment to realize that she meant her Bush drawings (pictured), a series of the president looking sour in the aftermath of Katrina, entitled “Bush and His Shadow.” So I gave them a look, and then we were on our way, done with the Annual Gowanus Artists Studio Tour for another year, and headed over to Cafe Mexicano for hot chocolate and excellent Mexican dinners for cheap.

My apologies to the artists I’ve failed to mention, and those whose studios I failed to see (#11, #12 and #13). And to all the artists, thanks for opening up your studios and sharing your work, and for doing the work in the first place. See you next year!