Phoenix, AZ

Phoenix has been very chill.

After months of not very chill — all that leaving New York (twice), punctuated by a whirlwind five weeks of intensity in Asia and capped by a couple of weeks of near-constant Jewish holidays in the company of a seven-month-old who has just learned how to climb up high enough to fall on his head — it has been a pleasure to be somewhere relaxed and easy.

Picking a direction home

I feel like I’ve been here a very long time, though it’s been just three weeks. I suppose it’s the first place that has felt like home in quite a while — maybe since June, when my girlfriend left New York, and New York began to feel like ex-home, a place I was closing up and shutting down.

I have made a conscious decision to think of Phoenix as home, of this house I own, this house where my parents are retired and where my stuff lives in boxes in the shed out back, as home. Someday Korea will be home, but it isn’t yet. I didn’t want to go off backpacking in Southeast Asia with no direction home, no sense of a place in mind that I can think of as the safe retreat if ever I need it. I don’t expect to need it, but it’s good to know where home is, even if you never plan to actually live there.

And I like Phoenix. As a place to live, it’s not bad. The weather is great — not just the warm and sunny you think of, but the crazy storms with the constant lightning and horizontal rain that come sweeping through and last twenty minutes. The storms here are about the best anywhere, and everything is dry again an hour later.

Phoenix days

So what have I been up to?

Sleeping late. Getting up, making coffee, going out for Mexican food for lunch. Treading water in the pool for exercise in the afternoon. Writing. I’ve finished a draft of my Vietnam book, and no, you can’t read it.

I’ve spent some time with my sister too, going to an Arizona State football game and a Phoenix Suns basketball game and a Make-A-Wish walk and the Phoenix Art Museum (“Art is our middle name” say the T-shirts) and a hike up north.

Beyond that, there’s been a lot of logistical stuff of the kind you do before you leave the country for a long while: getting an Arizona driver license and an international driving permit, buying travel insurance, getting a trust and a will and setting up durable power of attorney and making multiple visits to the notary at the UPS store, organizing boxes of my stuff in the shed out back, going to Target too many times and spending too much money on a year’s supply of drugs and toiletries. I have enough Imodium that I could stop pooping for a year, though that seems like maybe not the best idea, because that’s the number of pills that come in a Costco bottle of Imodium.

Like I said, chill. I’ve enjoyed the time with my parents, the relaxed flow of their retired life. It has been easy. I will miss it.

Back on the road

In another couple of days I’ll be on my way again. I’m nervous about hitting the road once more, a jittery feeling I’ve channeled into fussing over all the things I’ve packed and wondering how my bag is already this overstuffed when I haven’t gone anywhere or bought anything yet. (To be fair, it weighs only 32 pounds, not counting the stuff that’ll go in my carry-on. At some point I should probably make the inevitable blog post about what I’ve taken with me as gear.)

But the nerves will pass, I’m sure, once I’m in the thick of things. Next up is Seattle for a week (October 22-27) to visit one of my very best friends in the world, and then I’ll be on to Bangkok, arriving on October 29.

The adventure resumes!

Phoenix

Phoenix, AZ

Phoenix has been very chill.

After months of not very chill — all that leaving New York (twice), punctuated by a whirlwind five weeks of intensity in Asia and capped by a couple of weeks of near-constant Jewish holidays in the company of a seven-month-old who has just learned how to climb up high enough to fall on his head — it has been a pleasure to be somewhere relaxed and easy.

Picking a direction home

I feel like I’ve been here a very long time, though it’s been just three weeks. I suppose it’s the first place that has felt like home in quite a while — maybe since June, when my girlfriend left New York, and New York began to feel like ex-home, a place I was closing up and shutting down.

I have made a conscious decision to think of Phoenix as home, of this house I own, this house where my parents are retired and where my stuff lives in boxes in the shed out back, as home. Someday Korea will be home, but it isn’t yet. I didn’t want to go off backpacking in Southeast Asia with no direction home, no sense of a place in mind that I can think of as the safe retreat if ever I need it. I don’t expect to need it, but it’s good to know where home is, even if you never plan to actually live there.

And I like Phoenix. As a place to live, it’s not bad. The weather is great — not just the warm and sunny you think of, but the crazy storms with the constant lightning and horizontal rain that come sweeping through and last twenty minutes. The storms here are about the best anywhere, and everything is dry again an hour later.

Phoenix days

So what have I been up to?

Sleeping late. Getting up, making coffee, going out for Mexican food for lunch. Treading water in the pool for exercise in the afternoon. Writing. I’ve finished a draft of my Vietnam book, and no, you can’t read it.

I’ve spent some time with my sister too, going to an Arizona State football game and a Phoenix Suns basketball game and a Make-A-Wish walk and the Phoenix Art Museum (“Art is our middle name” say the T-shirts) and a hike up north.

Beyond that, there’s been a lot of logistical stuff of the kind you do before you leave the country for a long while: getting an Arizona driver license and an international driving permit, buying travel insurance, getting a trust and a will and setting up durable power of attorney and making multiple visits to the notary at the UPS store, organizing boxes of my stuff in the shed out back, going to Target too many times and spending too much money on a year’s supply of drugs and toiletries. I have enough Imodium that I could stop pooping for a year, though that seems like maybe not the best idea, because that’s the number of pills that come in a Costco bottle of Imodium.

Like I said, chill. I’ve enjoyed the time with my parents, the relaxed flow of their retired life. It has been easy. I will miss it.

Back on the road

In another couple of days I’ll be on my way again. I’m nervous about hitting the road once more, a jittery feeling I’ve channeled into fussing over all the things I’ve packed and wondering how my bag is already this overstuffed when I haven’t gone anywhere or bought anything yet. (To be fair, it weighs only 32 pounds, not counting the stuff that’ll go in my carry-on. At some point I should probably make the inevitable blog post about what I’ve taken with me as gear.)

But the nerves will pass, I’m sure, once I’m in the thick of things. Next up is Seattle for a week (October 22-27) to visit one of my very best friends in the world, and then I’ll be on to Bangkok, arriving on October 29.

The adventure resumes!

Phoenix

Groceries

Chinatown vs. New York

When I first discovered New York, it was a city of districts: the Diamond District on 47th Street, the Garment District in the West 30s, even a Lighting District on Bowery and something of a Porn District around Times Square. There were exciting pockets of Manhattan where beautiful things could spring up — an avant garde theater on Ludlow Street, say — and places like Canal Street where you could find incomprehensible sheets of plastic or weird electronics for sale. New York felt like a place that you could do or get or see anything. The New York I left behind is a much more homogenized city, where every Manhattan neighborhood has a Starbucks and a Banana Republic and $3,000+ 1-bedrooms.

But not Chinatown. In New York Magazine, Nick Tabor has written a piece about how Chinatown has stayed Chinatown (and got a quote from the fabulous Christina Seid, owner of the Chinatown Ice Cream Factory). The reasons are complex, and there’s no single factor that has kept Chinatown an island of funky distinctiveness in a city that feels more and more alike wherever you go.

The Chinatown story — and there’s probably a similar story to be written about Manhattan’s Korea Town — is a reminder that gentrification, homogenization, and the pricing out of immigrants and young creatives is not an inevitability. It doesn’t have to be the way it is, and there is no ironclad law of capitalism or free markets that says otherwise.

Chinatown was one of my favorite parts of New York City. It felt alive and vibrant and strange. It has retained its capacity to surprise. Is there a way that the Chinatown model of local ownership and control can make other parts of New York — or other parts of America — as interesting?

The Lure of Asia

The American Museum of Natural History’s Hall of Asian Peoples, inaugurated in 1980, opens with a diorama of a Samarkand market stall, undated, over which is the tag line “The Lure of Asia.” One couldn’t ask for a more perfect example of the kind of Orientalism Edward Said took to task four years earlier. There’s the othering — Asia is only a lure to non-Asians; for actual Asians, it’s just home — and the presentation of authentic Asianness as an undated premodernity. You see the same thing over and over throughout the exhibition, like the bier that’s presented as part of a Chinese marriage, with no notion that Chinese marriages in 1980 might be any different from whatever they were in the static eternal traditional past.

For all its flaws, though, the Hall of Asian Peoples was at least an attempt to make Asian culture, traditions, and artifacts legible to an audience unfamiliar with them. It belongs to a different era of ethnography — one corner describes “man’s rise to civilization,” as if it were unidirectional and didn’t involve women — but it’s not irresponsible. The collection is presented carefully, thoughtfully, with great attention to detail and a genuine attempt to respect the cultures presented.

The same, alas, can’t be said for China: Through the Looking Glass, the Costume Institute show at the Metropolitan Museum. The exhibition begins with a wall text that name-checks Edward Said in order to cast aside any serious reckoning with Orientalism as a field of power relations, choosing instead to see Asia as a source of inspiration and creativity for Western artists through the ages. All well and good, except that the show then colonizes the entirety of the Met’s Chinese art galleries, literally casting them in its own light, and making the objects and history of the actual China almost impossible to see. If it’s a show about Orientalism in action, it delivers.

At the Met, the Chinese galleries begin with the monumental, breathtaking 14th-century Buddha of Medicine Bhaishajyaguru, which, at 25 feet by 50 feet, gives a sense of the grandeur of Chinese tradition. Except that now you can’t see it, because of forest of glass bamboo poles is in the way, a work meant to reflect, I suppose, the repeating film clip we see of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.

The takeover continues, as the long hallway of early Chinese art is dimmed, lit in weird colors, and overtaken by an unnecessary wash of vaguely Asianish synth washes for no discernible reason. The Astor Court, normally an elegant refuge, is turned into a sordid nightclub, the rear wall lit red, the floor covered in black plastic meant to look like lacquer, the usual hush overtaken by kung fu movie sounds. The weird, bad lighting throughout — meant, I imagine, to preserve the clothing — destroys any opportunity to engage with the Met’s substantial Chinese art collection on its own terms. The exhibition even wanders down into the Egyptian wing, as if to say a little hello to Edward Said’s corner of the world. And you can’t escape the noise of this behemoth, even when you sneak off into the Chinese decorative arts, or the Korean collection, or the Gandharan Buddhist sculptures. Like any colonizing force, it’s insidious.

The exhibition tries to be clever, juxtaposing dresses and historical pieces. Sometimes it works, and other times it’s just facile. It might have been kind of hip if it had been put in the Costume Institute, or in its own special exhibition area. Instead, it’s just unnerving and weird: you look for your favorite pieces, like the Han Dynasty dancer, and they’re gone, only then you find them in some dim Plexiglas vitrine next to a dress with a dreadful Asiatic kitsch hat thrown on top for no good reason.

It is, I think, the first show I’ve ever seen at the Metropolitan Museum that actually pissed me off. I wanted to go look at the Chinese art, and it was buried. Fashion has a nasty habit of borrowing and burying, and also a nasty habit of turning Asia into raw material, whether it’s silk, ideas, or labor. That the Met gave it free rein to do so in its Chinese galleries is a disappointment.

Rathole

NYC

It may be a rathole,

But it’s the biggest rathole

It’s the best rathole

And damn if that ain’t something!

Something I wrote probably in 1993 or so, found written in the margins of a photocopy of a page of How Does a Poem Mean?

Travel and frozen time

I know what India’s like. I know because I’ve been there.

That’s how I tend to think, anyway. But do I really have any idea what India is like now? I first went there in 1997, spending four months backpacking alone around the Subcontinent. I returned for another six months in 2002, and then I made a brief, two-week visit for business in 2009.

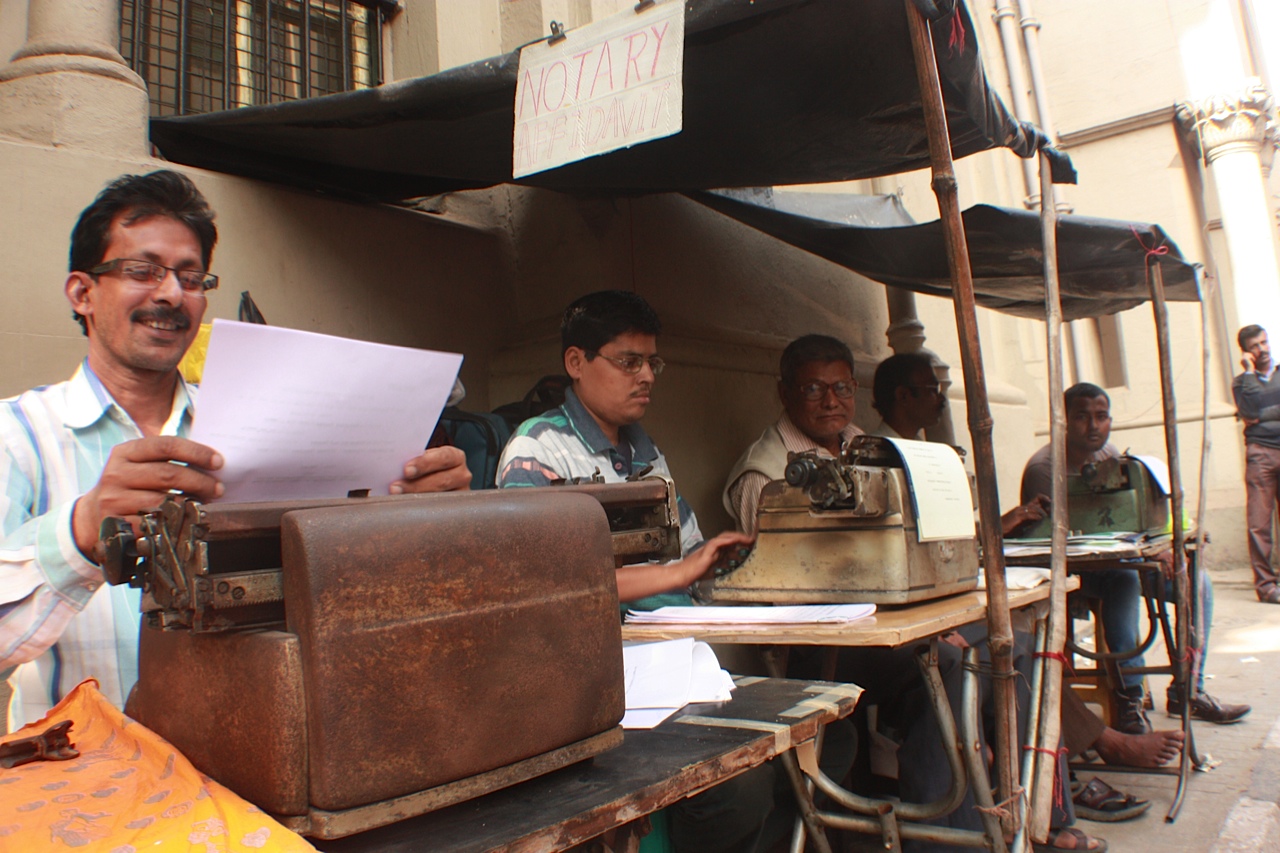

I still describe experiences and memories from that first trip as if that’s just how things are done in India. Yet that trip was 18 years ago. Back then, cassette shops sold music, Internet cafes connected through dialup twice a day to send and receive emails at their own POP addresses, and typists plied their trade (they’re still around, but a dying breed). No one talked about an IT revolution in India — the dot-com boom hadn’t even hit America yet. Business, it seemed, ran on hand-written ledger books. This was the very end of the Congress Party’s long era of dominance: the BJP was running hard, and they won enough seats to form a government under Atal Bihari Vajpayee just a month after I left the country, and the country tested its nuclear weapons a few months later.

Change, in other words, was coming, if you could see the signs. I gathered some sense of the political shift during my travels, but I had no idea about the economic and technological revolution that would transform the country. When I came back in 2002, Internet cafes were everywhere, with uninterrupted power supplies and Internet Explorer 5. CDs had replaced cassettes. Indian Railways was so effectively computerized that a clerk gave me my change when I switched my ticket time and the new one turned out to be cheaper.

I saw further changes when I went back to India in 2009: shopping malls, an emerging security state in the wake of the Bombay attacks, greater ambient wealth. India still felt very much like India, but it wasn’t quite the place I experienced back in 1997.

My frozen home

This frozen-in-time quality is typical of travel accounts — I grew up on my parents’ tales of what Europe was like, as their late-sixties experiences receded ever further back in time — and maybe even more typical of how expats and exiles think of their former homes. It’s funny to me the extent to which parts of Flushing feel more like the Korea of 2001, or even earlier, than like the Korea of today. Restaurants like Kum Gang San cater to Koreans of a certain age, and of a certain Korean era. My parents’ New York City, which they left in the 1970s, is not the New York City I live in.

And very soon, I’ll be talking about a New York City that will be frozen in time.

I’ve been here since 1993, which is quite a while. I’ve seen in change. I’ve called in a dead body in Hell’s Kitchen, and done it on a payphone. I used to go to the 2nd Ave Deli on Second Avenue, and I used to ride the Redbirds out to Jackson Heights for Indian food and not Tibetan food. I remember Pearl Paint and the Twin Towers and the Barnes & Noble on Sixth Ave and the old, hideous Columbus Circle and tokens. A lot has changed.

And it will keep changing without me, after I leave. In a few years, I will be telling someone about New York, and all the hipsters in Bushwick or how Citibike works or how much fun it is to get some ice cream from Chinatown Ice Cream Factory and go to Columbus Park to watch the old men gamble and the old ladies sing, and some actual New Yorker will interject that actually it’s not like that anymore, that they cleaned up the park, changed the bike laws, and moved all the hipsters to Brownsville.

The passage of time

I suppose this is also just a function of getting older. When I was a kid in the eighties, I imagined that the styles then in fashion, music, film, whatever, were just the defaults. I’ve now been around long enough to see things I remembered from the first time come back into style and then go out again. I am aware of the passage of time in a way I couldn’t have been when I was younger.

But then there’s New York. I’ve been here long enough that it’s my home and nowhere else is, but I’m leaving. And New York isn’t a place you can hold onto. It moves on without you. It does not, frankly, give a shit about you, especially if you’ve gone off to live somewhere else. You keep up with New York, not the other way around. Quicker than most places, New York erases and replaces the things you knew.

Well, quicker than most places in America, anyway. Eventually I’ll be settling in Seoul, a city that changes even faster than New York — where you can leave for three years and not be able to find your old neighborhood because the whole thing has been bulldozed and replaced.

And in the meantime? I’ll be traveling, gaining new slices of experience, and trying to remember later when I talk about them to say, “This is how it was then,” instead of “This is how it is.”

Travel and frozen time

I know what India’s like. I know because I’ve been there.

That’s how I tend to think, anyway. But do I really have any idea what India is like now? I first went there in 1997, spending four months backpacking alone around the Subcontinent. I returned for another six months in 2002, and then I made a brief, two-week visit for business in 2009.

I still describe experiences and memories from that first trip as if that’s just how things are done in India. Yet that trip was 18 years ago. Back then, cassette shops sold music, Internet cafes connected through dialup twice a day to send and receive emails at their own POP addresses, and typists plied their trade (they’re still around, but a dying breed). No one talked about an IT revolution in India — the dot-com boom hadn’t even hit America yet. Business, it seemed, ran on hand-written ledger books. This was the very end of the Congress Party’s long era of dominance: the BJP was running hard, and they won enough seats to form a government under Atal Bihari Vajpayee just a month after I left the country, and the country tested its nuclear weapons a few months later.

Change, in other words, was coming, if you could see the signs. I gathered some sense of the political shift during my travels, but I had no idea about the economic and technological revolution that would transform the country. When I came back in 2002, Internet cafes were everywhere, with uninterrupted power supplies and Internet Explorer 5. CDs had replaced cassettes. Indian Railways was so effectively computerized that a clerk gave me my change when I switched my ticket time and the new one turned out to be cheaper.

I saw further changes when I went back to India in 2009: shopping malls, an emerging security state in the wake of the Bombay attacks, greater ambient wealth. India still felt very much like India, but it wasn’t quite the place I experienced back in 1997.

My frozen home

This frozen-in-time quality is typical of travel accounts — I grew up on my parents’ tales of what Europe was like, as their late-sixties experiences receded ever further back in time — and maybe even more typical of how expats and exiles think of their former homes. It’s funny to me the extent to which parts of Flushing feel more like the Korea of 2001, or even earlier, than like the Korea of today. Restaurants like Kum Gang San cater to Koreans of a certain age, and of a certain Korean era. My parents’ New York City, which they left in the 1970s, is not the New York City I live in.

And very soon, I’ll be talking about a New York City that will be frozen in time.

I’ve been here since 1993, which is quite a while. I’ve seen in change. I’ve called in a dead body in Hell’s Kitchen, and done it on a payphone. I used to go to the 2nd Ave Deli on Second Avenue, and I used to ride the Redbirds out to Jackson Heights for Indian food and not Tibetan food. I remember Pearl Paint and the Twin Towers and the Barnes & Noble on Sixth Ave and the old, hideous Columbus Circle and tokens. A lot has changed.

And it will keep changing without me, after I leave. In a few years, I will be telling someone about New York, and all the hipsters in Bushwick or how Citibike works or how much fun it is to get some ice cream from Chinatown Ice Cream Factory and go to Columbus Park to watch the old men gamble and the old ladies sing, and some actual New Yorker will interject that actually it’s not like that anymore, that they cleaned up the park, changed the bike laws, and moved all the hipsters to Brownsville.

The passage of time

I suppose this is also just a function of getting older. When I was a kid in the eighties, I imagined that the styles then in fashion, music, film, whatever, were just the defaults. I’ve now been around long enough to see things I remembered from the first time come back into style and then go out again. I am aware of the passage of time in a way I couldn’t have been when I was younger.

But then there’s New York. I’ve been here long enough that it’s my home and nowhere else is, but I’m leaving. And New York isn’t a place you can hold onto. It moves on without you. It does not, frankly, give a shit about you, especially if you’ve gone off to live somewhere else. You keep up with New York, not the other way around. Quicker than most places, New York erases and replaces the things you knew.

Well, quicker than most places in America, anyway. Eventually I’ll be settling in Seoul, a city that changes even faster than New York — where you can leave for three years and not be able to find your old neighborhood because the whole thing has been bulldozed and replaced.

And in the meantime? I’ll be traveling, gaining new slices of experience, and trying to remember later when I talk about them to say, “This is how it was then,” instead of “This is how it is.”