I have, at long last, posted my master’s thesis online. Called Swiss Gods Don’t Like Rice Cake, it tells the story of how Korean shamanism has begun to incorporate non-Koreans as shamans. You can find it here.

Hitting the News in Vietnam

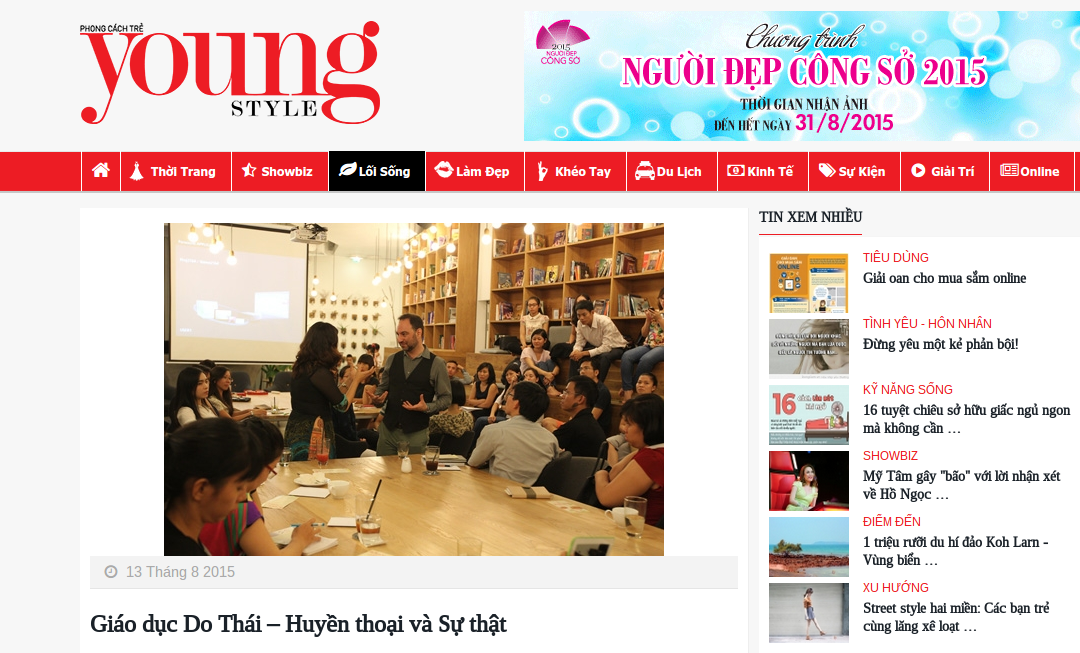

With the help of education entrepreneur Catherine Yen Pham, I have now made the Vietnamese news. Two articles have come out so far — one in Young Style, another in Family Life — and I’ve been told more are on the way.

The articles are about the talk I gave in Ho Chi Minh City about Jewish traditions of education. Catherine and I spoke to an audience of about 120 people, plus press, for several hours, including an extended Q&A session. I was amazed at how interested people were, how hungry they were for new ideas about how they can best raise their children. They want to do better. Many of them were taking notes. A lot of Asians, Vietnamese included, are convinced that Jews are smart, good with money, rich, powerful, and maybe slightly magical. I wanted to share with them some good points from Jewish culture, while at the same time puncturing some of the myths.

It’s an irony for me that after years of focusing on Korea, and pretty much an adult lifetime of distancing myself from Judaism, or at least Orthodox Judaism, I am now on my way to becoming an expert on Judaism in Vietnam. Catherine and I have begun work on a book, and it would also be pretty ironic if my first book were to be in Vietnamese — and about Judaism. But life is funny that way.

Identity and geography

When I was a baby, my parents began to worry about my Jewish identity. They’d grown up in New York, where everyone they knew was Jewish, but how would I know what it meant to be Jewish as I grew up in Marin County, California? That’s what first drew them toward greater involvement with first Reform Judaism, and then the Orthodox Judaism that has become a core part of their lives.

I sort of reverse-solved the problem my parents had raised by moving right back to New York, where I could have almost no religious involvement with Judaism and still be Jewish without having to think about it. In New York, there are Jews all around me. We share a culture. No need for a whole lot of fancy stuff to get the point across.

But I have found that at the various points in my life when I’ve been away from New York, and especially in Asia, identifying as Jewish has become more important and more interesting. Before I left on my current trip to Vietnam and Korea, I got myself a Jewish star to wear around my neck, and I’ve had several occasions where the easiest way to explain who and what I am was to pull it out and show it. Jewish culture — and, yes, the Jewish religion I don’t really believe in — are a core part of who I am.

Jewish wisdom

In being asked to speak about Jewish values, I’ve had to take a close look at my own values. After all, I’m not about to begin espousing a set of ideas that I don’t agree with. I’ve looked to find where what I believe aligns with Jewish traditions, and to find ways of presenting these ideas to an audience that doesn’t know the first thing about Judaism.

It turns out — not a big surprise, really — that there’s a lot in Judaism that I agree with and am proud to be able to share: the Jewish concern with ethics and charity, the Jewish passion for questioning and curiosity, Jewish humor, the Jewish tendency to be able to hold multiple opinions at once. And despite my frustrations with it along the way, it looks like all those years of Jewish education actually taught me something useful.

Maybe this isn’t quite what my parents were after, but the son they raises is certainly aware of his Jewish identity.

Where are the ones who condemn?

This is a question that one hears after atrocities: where are the people of the same group — Muslims or blacks, usually — who condemn the ugly acts of violence perpetrated in their name? I hear this complaint often from supporters of Israel. They are making the case that terrorists who fire rockets into Israel or stab people in synagogues are representatives of the true will of the great mass of Muslims and Arabs. If that’s not true, then where are the Arab and Muslim condemnations of such violence?

The answer is that they are in the places you would expect them to be: the Arab and Muslim press, in the languages spoken by the communities involved. Or they’re easily accessible in the English-language Arab press, where an Arab Muslim cartoonist had this to say about the Charlie Hebdo attack:

I condemn the attacks on the cartoonists even though I don’t agree with the publication’s editorial slant, which I have often found to be hurtful and racist. Nevertheless, I would continue to stand for their freedom of speech.

Which is pretty much what I think too.

This time, the condemnations are easy to see because they’re in cartoon form. Here’s a whole set of Arabic cartoons condemning the attacks. Take a look and remember that there are Arabs and Muslims who are as disgusted and disappointed by murder in the name of Islam as you are, or maybe more so.

The pleasures of transit

I’ve been meditating for the past month, using Headspace (I get it discounted as a Google employee benefit). It’s a series of guided mindfulness meditations hosted by Andy Puddicombe, who sounds like the GEICO Gecko. Each day, the GEICO Gecko tells me to take some deep breaths, leads me through a body scan, reminds me to let thoughts come and go. There are times when I want to do it and times when I very much don’t. But has it been having any effect?

There are few better tests of mindfulness and patience than transit. Yesterday I flew from JFK in New York to Phoenix, on an oversold flight the Saturday before Christmas. I thought of Radiohead:

Transport

Motorways and tramlines

Starting and then stopping

Taking off and landingThe emptiest of feelings

As they announced a last-minute gate change, sending the mass of passengers scurrying across the terminal, I felt the pull of that kind of numb irritation. But I made a choice to approach the experience differently. At that second gate, as an entire planeload of people mobbed the counter, I went to look out the window at the ground crew attaching the terminal ramp to the plane, balancing on a high platform to open the plane door and roll in the food carts, putting down and taking up chocks. I noticed the hashes on the ground for where different models of planes should pull in: 747, 777, Airbus 380, 767, 757. Inside the terminal, a sparrow was darting from window to window. A mother brought her toddler to the window and tried to point out the bird to him, but he was mesmerized by the big metal birds outside.

Getting on the plane, I stood beside the woman who was furious about being in Zone 3 and kept telling the counter staff, with tight-lipped determination, that “overhead space is my biggest concern right now,” as if no one else had luggage and the airline had never had to deal with a situation like hers before. Two different families on the ramp were dealing with crowds of children whose seats were somehow not adjacent to their parents’. On board, the young man next to me was coughing up a lung, and his father in the aisle had an argument with the flight attendant over his already-tagged bag that was supposed to be checked. The cabin was so cold that I kept on my hat and gloves. The pilot announced that our JFK ground time was estimated at 50 minutes.

There was every reason to be sour and annoyed, but somehow I wasn’t. I looked out the window. You could see Manhattan in the distance, the new World Trade Center tower, and the planes taking off in front of us were silhouetted against it. It was beautiful. In the air, I ate my overpriced terminal sandwich, put a travel mix on my headphones and took a nap. I woke up, meditated with Headspace. I tried watching Frozen, but it was terrible, so I turned it off. I looked out the window. By then we were over western Nebraska. There was a stripe of snow, maybe 50 miles wide and hundreds of miles long, across an otherwise undifferentiated flatness of squares and circles, as if a line of clouds had gotten exactly that far and said, “I think I’m gonna go right here.” I thought about how strange it is that I know Seoul and Beijing and Kathmandu better than I’m likely ever to know that farmland, that the chances of finding me in Omaha are far less than the chances of finding me in Phnom Penh or Vientiane. Then the farmland gave way to the layer cake buttes and canyons and the snowy mountains of New Mexico, and after a while that landscape changed into badlands where the icy rivers splayed out like white fractals, and then the land stepped down into the Arizona desert. It was beautiful. I took out my laptop and wrote about it, and I noticed that when I’ve meditated and been sober — the one other time I kept it up was when I lived in Korea — I’ve written more and more freely. I almost didn’t want the flight to end. Almost.

*

There are two related thoughts that transit evokes: that nowhere is anywhere, and that everywhere is everywhere else.

The first thought is the numbness that comes over us, the feeling that we’re in non-space, non-time. It’s easy to feel like a dead thing when you’re in the TSA line. (As Talking Heads put it, “I’m tired of looking out the windows of the airplane / I’m tired of traveling, I want to be somewhere.”)

The second thought is the unnerving feeling that planes and technology are shrinking the world, that there is no escape, that wherever you go will be the same as wherever you left. This illusion is brought on by the weird sameness of airports, airplanes, transit lounges, duty free shops, chain hotels. But these places need to be legible and at least minimally palatable to travelers from everywhere, and they need to be interoperable with planes coming in from wherever. Airports aren’t the world. The world is still out there in all its everyday strangeness. Omaha retains its mystery, if you’re open to that.

But contra Talking Heads, nowhere is nowhere, and everywhere is somewhere — even airplane cabins and duty free shops. We’re always in transit: through time, through space. We’re always between things. Something is always ending, something has always not yet begun. But we are always somewhere. And I’m finding, for myself, that the simple practice of noticing where I am makes being there less frustrating, more interesting, more worthwhile. It’s counterintuitive, but when I stop resisting the irritations, stop forcing them away, they lose much of their power. Even at the airport.

Hanukkah

Hanukkah is a dumb holiday, and it’s my favorite.

I grew up with a weird amalgam of Jewish influences: an early childhood of high-style Reform Judaism gave way to my parents’ increasing devotion to the Chabad Lubavitch brand of Chassidic Orthodox Judaism, while I spent my summers at the Conservative Jewish Camp Arazim and attended the nominally Orthodox, highly disorganized and very Russian Hebrew Academy of San Francisco from third through eighth grade. My Judaism was pulled in different directions. I loved the high-church elegance of Reform, but it was pretty square, and I suspect I would have found it boring had I stuck with it into my adolescence. Orthodox Judaism, and especially Chabad, was full of baffling rules and boring prayer and eternal Saturdays full of Monopoly games and quietly setting fire to things while waiting for the sun to go down, but it offered periodic bursts of completely batshit alcohol-fueled celebration from which teenagers were by no means excluded. (The Hamantashen Riot of ’87, at a shul in San Francisco, became something of a legend.) And Conservative Judaism, sitting somewhere in the middle, was too chummy and too Zionist, but its passion for teaching young Jews to hook up with other young Jews was pretty compelling that summer I turned 16.

Today my connection to Judaism as a religion is pretty tenuous, and mostly it involves family: I go to shul when I visit my parents or my brother, who’s studying to be a rabbi, or I go to holy sites in Israel with my sister, or I go to the Passover seder out on Long Island with cousins. There’s not much that I do on my own. But I do Hanukkah.

Hanukkah is a dumb holiday because it celebrates the victory of a short-lived fundamentalist movement over the forces of tolerance, and it’s a dumb holiday because the attention it receives in America today is a product of American Jews’ desire for something to compete with Christmas. If you’re a Christian, the birth of Jesus is pretty important. If you’re a Jew, the victory of the Maccabees over the Assyrian Greeks is pretty low on the list of important things. It’s like a holiday celebrating the Battle of Manila or something.

Hanukkah is maybe the only part of Judaism that bridges the different parts of my Jewish experience. I loved it when I was little, when we would light the menorahs in the high windows of our formal living room that faced out to the street, and then sit in the part of the house we saved for special occasions and unwrap presents. Presents are excellent. Anticipating another one tomorrow is excellent. Getting the biggest Space Lego set of the year is beyond excellent. Gold-wrapped chocolate is OK too, not great, but who’s gonna complain about chocolate? Dreidel is a stupid game, but that’s OK because no one actually plays it. Hanukkah music is terrible, but who listens to Hanukkah music? We listened to my parents’ psychedelic rock records from the sixties. Latkes are great and we probably had them, I don’t know; I was busy with the Legos.

As my family became more Orthodox, holidays that had once been breezy and fun, like Passover or Purim or Simchas Torah, began to involve long compulsory prayer sessions and elaborate rules and restrictions. But that never happened to Hanukkah. Hanukkah was still about candles and presents, without much in the way of additional prayer time. And the new rules made Hanukkah better, because it meant we now set fire to olive oil instead of candles, and playing with fire is always improved by added complexity and liquid fuel. Even the Chabad menorah lightings in San Francisco’s Union Square managed to add to the awesome: they were trips to the city, at night, and one year Carlos Santana played.

There have been years when I missed Hanukkah. I didn’t light the candles when I was in India, and I don’t remember lighting them when I lived in Korea either. But I’ve lit candles in all my different homes in New York City over the years, and with my family in Playa del Carmen (where dueling Chabads have dueling menorah lightings). I lit candles tonight, in the window, in a kosher menorah, and I’ll keep lighting the candles through the end of the holiday, which I get to finish out this year with my family in Arizona. And next year, when I’m off somewhere in Southeast Asia, maybe I’ll drop in on a Chabad House or find some Israelis and do Hanukkah there too. If there’s one thing I’ve learned in my world travels, it’s that you can find sufganiyot anywhere.

[national fears]

Because I know a little something about Korea, people often ask me about the Chinese government. I suppose Canadians probably get asked to explain America, so I kind of get it.

In any case, a question that often comes up is why the Chinese government is so terrified of Falun Gong. I don’t know from any detailed insider knowledge or anything, but my guess is that it has to do with a vast and little-known war called the Taiping Rebellion.

At roughly the same time that some 600,000 Americans lost their lives in our Civil War, China was going through an epic struggle that cost some 20 million lives — some 30 times as many casualties. (I found one reference to China’s population in 1834 as 400 million, while the US had some 31 million in 1860, so the percentage losses are closer: something like 5% in China, and 2% in the US.)

Wars on this scale leave national scars. America certainly hasn’t resolved all the racial issues that lay behind the Civil War, and fear of race-based insurrection has continued to haunt the national psyche.

In China, the haunting fear is of a different kind. It’s a fear of disruptive religious movements, because that’s what Taiping was. Hong Xiuquan, the movement’s leader, claimed to be Jesus’s brother, and he led what was called the Heavenly Kingdom in a great battle to rid China of Manchu rule and spread a peculiar brand of heterodox Christianity.

So I don’t know this for a fact, but I suspect that when Chinese officials see a movement like Falun Gong — a religious movement with the power to mobilize great numbers of people — some national memory of the Taiping disaster kicks in. On a gut level, mass religious zeal produces panic.

None of this is meant to justify the abuse, repression, or torture of any group of people for their religious beliefs, of course. The question isn’t whether such repression is OK — it’s not — but why it happens, why this group in particular gets the Chinese government’s panties in a bunch. And I think that maybe it’s that legacy of Taiping.

[the cup]

Many years ago, I saw a lovely Tibetan film called The Cup. It has been a long time, but I finally watched it again, and I found it just as sweet, moving and lovely as before. It’s the story of some monks in a Tibetan monastery in northern India — refugees, mostly — and one young monk’s passion for soccer during the 1998 World Cup.

[fear]

I have been afraid of being alone for a long time. When I was very small, I surrounded myself with stuffed animals when it was time for bed, but sometimes they weren’t enough. Then I would get up and go to my parents, who, understandably, tried to get me back to bed. When I’d gotten up one too many times, my mother would send me back to my room and tell me not to come out again for 15 minutes.

I have been afraid of being alone for a long time. When I was very small, I surrounded myself with stuffed animals when it was time for bed, but sometimes they weren’t enough. Then I would get up and go to my parents, who, understandably, tried to get me back to bed. When I’d gotten up one too many times, my mother would send me back to my room and tell me not to come out again for 15 minutes.

This was unfair, I felt, for two reasons. First, I didn’t have a clock in my room, and even if I did, I couldn’t read it. But second, and far more vexing, was the fact that if a burglar were to come, he would have to come within some 15-minute period, so how could my mother be sure it wasn’t this 15 minutes? How would she like it if a burglar came and instead of coming out to get help, I stayed put until he snatched me away?

I have no idea how I came to fear burglars specifically. Our subdivision had had exactly one burglar in its entire history, and he had turned 18 and been arrested and sent away by the time I was old enough for two-syllable words. People left their doors unlocked and still do. But I was afraid a burglar would come, see the fire-department-issued “C” sticker on my windown (for Child’s Room) and decide to break in on the weakest member of the family.

This fear was connected to McDonald’s. Specifically, I had a fear of the Hamburglar and his hamburger-shaped head. The privet outside my window cast a shadow in that awful shape against the curtain, and it filled me with dread.

Except it turns out the Hamburglar never had a hamburger head. All these years, I’d conflated the Hamburglar with Mayor McCheese, putting the head of the latter on the body of the former.

Somehow this seems important. How many of my other childhood fears, still buried deep and leeching their toxins into the soil of my unconscious, are just as nonsensical? To what extent is every hurt and disaster in my life the product of a misapprehension?

As Zen Master Seung Sahn put it, “Only don’t know.”

[questions for the buddha]

Why is there suffering? Not what causes it, but why is the universe constituted in such a way that these causes manifest? Why do we live in a universe in which our Buddha natures are concealed?

Why is there suffering? Not what causes it, but why is the universe constituted in such a way that these causes manifest? Why do we live in a universe in which our Buddha natures are concealed?

If we all have Buddha nature and enlightenment is available to anyone, why have so few people achieved it?

If samsara has existed for infinite time and enlightenment is available to all sentient beings, why are not all sentient beings already enlightened?

[secrets and food]

I’m walking down Sixth Avenue on a Friday evening after work, hurrying to my therapist, a blue-green headache crawling over from the back of my skull towards my right eye. I’m hungry. I want meat. The Halal Foods truck isn’t open yet, and the cart in front of the Best Buy on 23rd has nothing but pretzels. Time is running short. I duck into the CVS on 25th and browse the snacks. Jerky is ridiculously expensive. I settle for a cannister of Slim Jims. They’re greasy in a queasy way, but they have the mix of salt, fat, protein and umami that I’m craving. They get me through.

I’m walking down Sixth Avenue on a Friday evening after work, hurrying to my therapist, a blue-green headache crawling over from the back of my skull towards my right eye. I’m hungry. I want meat. The Halal Foods truck isn’t open yet, and the cart in front of the Best Buy on 23rd has nothing but pretzels. Time is running short. I duck into the CVS on 25th and browse the snacks. Jerky is ridiculously expensive. I settle for a cannister of Slim Jims. They’re greasy in a queasy way, but they have the mix of salt, fat, protein and umami that I’m craving. They get me through.

I stuff the cannister in my bag, and when I get home, I slip it into a dresser drawer. I don’t want Jenny to see. I’m ashamed of having bought such down-market junk food. I’m afraid she’ll think I’m disgusting for eating it, for wanting to eat it. There’s no reason she needs to know.

This is the insanity from which I am working to recover. I confessed to Jenny last night about the Slim Jims, though it hardly counts as a confession considering that I hadn’t done anything wrong. It made her laugh. What’s especially ridiculous about the whole thing is that I went with Jenny to McDonald’s on Saturday to indulge her particular junk food craving. Why would she have a problem with mine? But I had to confess because the mechanism of this secret-keeping — the shame, the hiding, the justification — was exactly the same as the mechanism for much bigger, more serious secrets.

This incident has got me thinking now about my relationship with food. I don’t think of myself as someone with an eating disorder, though I tend to overeat from time to time (like most Americans) and to treat emotional distress with tasty treats (also like most Americans). But my psychological relationship with food is nevertheless tangled.

I grew up in Northern California in the late 1970s and 1980s, an era when food virtue replaced religion for many people. Terms like “macrobiotic” and “Pritikin” and “organic” were in the air, and food allergies were just coming into fashion. For children, the complex restrictions, and the earnest moral tone that went with them, was often bewildering, especially in group settings. (I still harbor a bitterness about efforts to convince me that carob was just like chocolate. It is not, and any idiot could taste the difference. It was insulting.)

My parents were pretty chill on the health food front, but beginning in my early childhood, a strange, isolating, ever-tightening net of restrictions began to enclose me, one intimately tied to morality and virtue: the laws of kashrus. At first we just kept kosher style, which was easy and kind of fun, offering a whiff of superiority without demanding much. We didn’t eat pork and we kept our milk and meat separate. No big. It meant we were better people.

But gradually the rules became stricter, and eventually we went wholly kosher: separate dishes for milk and meat, eating only products that were labeled with a hechsher, subscribing to newsletters that detailed the ongoing debates about even hechshered foods, waiting an hour (then three, then six) after eating meat before eating anything with milk in it. There were no kosher restaurants in Northern California, so that was out too. Chinese food was gone from my life. Around friends, I was expected to keep track of a vast library of unacceptable treats and shun them when offered. No more Oreos. No more Starbursts. And there was always the danger that a beloved product would slip into doubt. Worse, my parents would make an exception for something they loved, and then one day decide — arbitrarily, as far as I could tell, and certainly without consulting me first — that the exception had to end.

Holidays brought other restrictions. Every couple of months, fast days came around, and from age 13 I was supposed to go either from sunset to sunset or from dawn to sunset, depending on the particular fast, with neither food nor drink of any kind. Before fast days, including the highly sacred Yom Kippur, I would sneak extra snack food into my room, but I was always careful tokeep myself hungry enough to eat a lot when the fast ended. Passover was a week of confusion and despair, as the available foods were limited to the flavorless and the difficult; I lived primarily on macaroons, leftover roast from the Seder, and a sort of matzah-based breakfast cereal my mother concocted, and which was always under threat from a potential restriction on gebruchts, or matzah that has become wet.

Added to those food issues was my father’s ongoing hectoring of my mother about her weight. She wasn’t ever obese or even very chubby, but neither was she the hot-bodied 19-year-old he married and painted in a bikini, and I don’t think my father accepted easily that my mother’s body was simply never going to return to the state it was in when she was getting catcalls across Europe in 1966. And none of us could help but be aware of my maternal grandmother’s long struggle with serious obesity, punctuated by crash diets and involvements in OA.

That this way of life led to secrecy and dualism is hardly surprising. I wanted to be a good son and a good Jew. I also wanted to eat things that tasted good. What alcohol or cigarettes or pornography are for some kids, bacon and Nabisco products were for me. Except that in other people’s homes, these things were completely normal. When Dan down the street got his Easter basket full of Starbursts and offered to share, I didn’t say no. By the time I reached adolescence, when constant hunger and rebellion are pretty much the norm anyway, I was willing to break food rules whenever I could. In high school, I would drive down to the mall and eat a big plate of Chinese food for lunch, savoring the pork dishes. It wasn’t that I went out of my way to eat pork specifically, but that I wanted to eat what I wanted to eat, without restrictions from my parents.

And I wanted to eat in restaurants. I wanted to be normal. When Joey got into Thai food — his parents were much slower to adopt the full religious regimen — I wanted to know what he was excited about. My parents actually mocked the food freaks with their semi-imaginary health fragilities, somehow never realizing that they’d turned me into the nerdy kid with the milk allergy. (Later, in my pot-smoking years, when I shunned tobacco-mixed spliffs because tobacco gives me headaches and tastes lousy, I usually felt it necessary to make some comment like, “I hate to be the kid who says, ‘I cannot have milk because I have a lactose intolerance,’ but I really don’t like tobacco.”) It was one more of the many, many ways that Orthodox Judaism isolated me and kept me alienated.

In my teen years, I would disappear into my room with a box of cookies and not return it to the kitchen. Did it take me a week to finish, or two days, or did I finish it that night? I kept the pace of my indulging secret from my parents so that they couldn’t scold me for overeating, or for the cost of my eating.

It was also in this period that I learned from my peers to feel moral and political shame around eating. My high school had militant vegans. Eating meat was bad. Eating environmentally damaging foods was bad. Mostly I made a mockery of this sort of thinking, but it affected me. And perhaps because of my own upbringing, I have found myself attracted to or in relationships with food moralizers quite often. Berit was a vegetarian who thought seasoning was creepy; T had complex ethics and aesthetics around food that kept me nervous and uncertain. To an extent, I think I hid the Slim Jims from Jenny because T might have scolded me for eating them. And I have sometimes waited for Jenny to go to bed so that I can snack without incurring her fear that I’ll get diabetes like her father.

But I like Slim Jims from time to time. I like Hormel chili. And more importantly, I have a right to like whatever I like. Food shame and food secrecy are habits that I need to break. They are part of my systems of indulging my own desires through secrecy rather than being open about what I want and need. And that has to change.