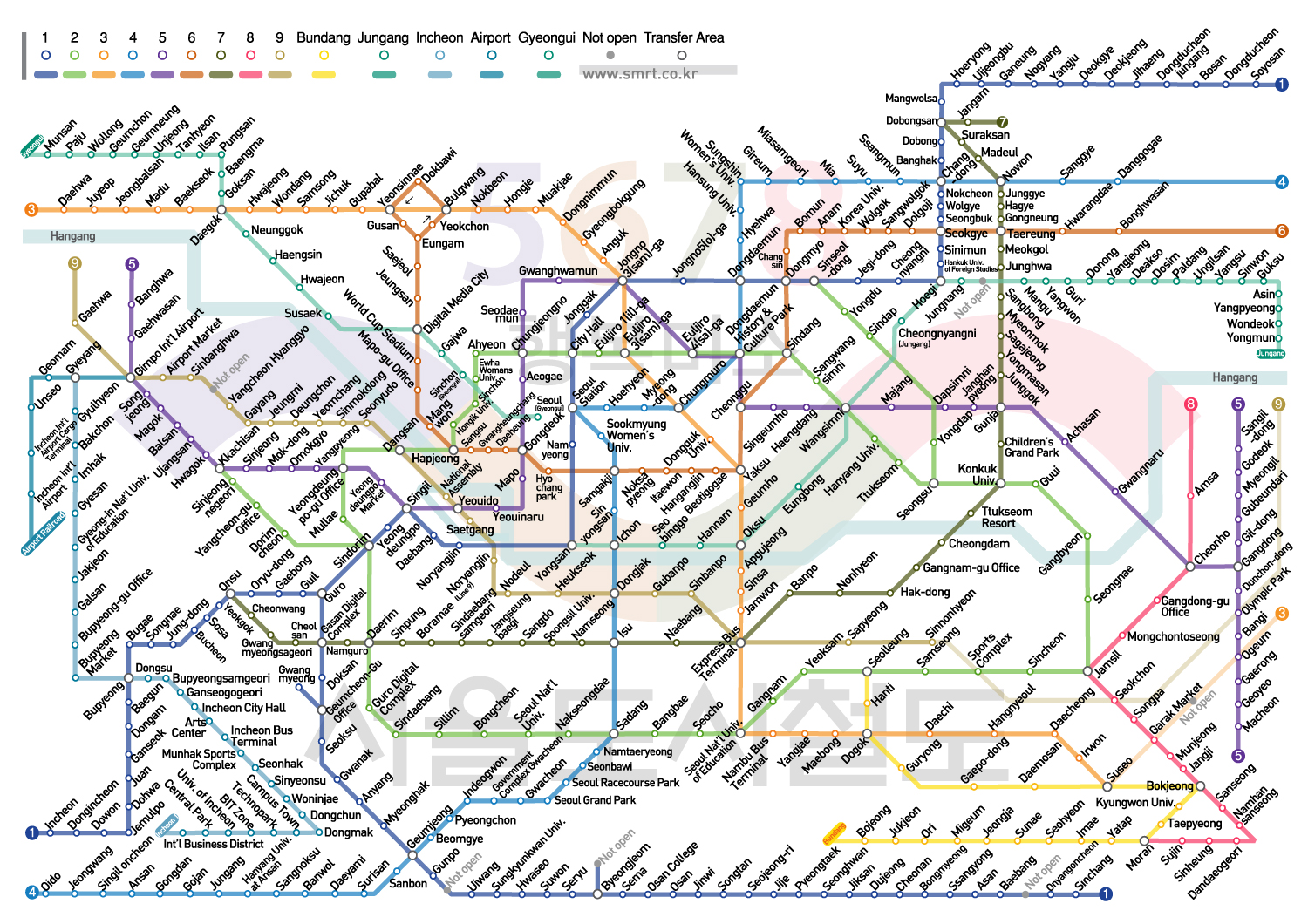

- Random station: Hongje/홍제역, Line 3

- Points of interest:

- Inwang Market/인왕시장

- The Ant Village/개미마을

- Hwanhuisa Temple/환희사

- Other stations visited:

- Muakjae/무악재역, Line 3

In feng shui (pungsu in Korean) the ideal location has a mountain to the north and water to the south, providing protection from Siberian winter winds and an open avenue for summer monsoon rains. That’s why both Gyeongbokgung Palace and the presidential Blue House sit at the southern foot of Inwangsan Mountain, facing Cheonggyechon Stream.

On the ass end of Inwangsan, out beyond the perimeter of the old city walls, is the opposite sort of place. Gaemi Maeul (개미마울) — The Ant Village — gets its name from the tenacity and hard work of its 400 or so residents, who’ve been crawling up and down the steep slope to their shantytown since the end of the Korean War. It’s also, perhaps, a statement about their relative importance in Seoul’s grander schemes.

Between a rock and a fast place

I came to The Ant Village on my first Seoul Subway Randomizer adventure, which began at Hongje Station on Line 7. My goal was to go look around in parts of Seoul I wouldn’t otherwise be likely to see, and Hongje was an excellent place to start.

Sandwiched between Inwangsan to the south and a highway to the north, Hongje has either fended off or been overlooked by the developers who’ve converted much of the surrounding area into especially soul-crushing variants of Korea’s ubiquitous vast apartment blocks. Its narrow, winding streets are still lined with the small brick apartment houses that Koreans call villas, and it looks as if no one has updated much of anything in the past forty years. Buildings and signs have old spellings — 자전차 (jajeoncha), an old word for bicycle, or a sad old apartment building called 만숀 (manshyon) instead of the more modern 만션 (manshyeon), the Konglish term so absurd it’s almost an insult.

My Korean friend and I made our way to Inwang Shijang, a traditional market that despite its typical array of Korean products — seafood, mystery twigs — had a torpid squalor that felt more like out-of-the-way markets in Vietnam or Myanmar than like anything I’ve seen before in Seoul. As we sat down for tteokbokki and fish cakes at one of the market stalls, my friend told me the place reminded her of her childhood in Daegu in the 1970s.

Up the ant hill

As the road began to climb, we came to the first of the old houses, an uneven concrete slab with a roof of corrugated metal. It’s the sort of thing you see on the outskirts of cities in developing countries all over the world, or in their neglected pockets — down by the river in Hanoi, say — and I have a Vietnamese friend who grew up in something similar in Saigon in the 1980s. But it was jarring to find this sort of house still operating as a going concern in Seoul in 2017, especially after starting the day in the LED-lit hypermodernity of Gangnam.

I suppose, though, that I was just coming face-to-face with a concrete (pun intended) manifestation of the poverty I see every day and mostly ignore: the old woman who sits on the steps in Gangnam Station every day, selling gum when she’s not drifting off to sleep; the old folks limping along as they push their filthy old carts past the Porches and Rolls Royces, collecting garbage to recycle. Next to my posh Gangnam apartment complex is a dingy brick apartment house above a parking garage, junk piled up in the narrow verandas you can see from the street.

In Seoul, it’s the elderly who seem to end up destitute most often. In an economy that has modernized as quickly as South Korea’s, it’s inevitable that a good part of the older generation would be left behind. In what is now one of the best-educated and most technologically advanced countries in the world, those who grew up during the Korean War and its aftermath may not ever have gotten past sixth grade or developed the kinds of skills a modern economy demands. What’s not inevitable is South Korea’s minimal social spending, which is among the lowest of any developed country. The scandal and disarray engulfing Korea’s conservative party might be an opening for a new direction; for now, the ants are still part of Seoul society, scurrying along the margins and subsisting on scraps.

The Ant Village

The Ant Village proper is a peculiar hybrid. Built by people with nowhere else to go after the Korean War, the worst houses are old and poor and dangerous, makeshift and constructed to no code, heated with the old yeontan charcoal bricks that produce carbon monoxide and occasionally kill people in their sleep, as happened to one of my Korean friend’s high school classmates. (Draftiness could, I suppose, be a lifesaver.)

But the residents — some of them, anyway — haven’t wanted to leave, and they’ve kept developers at bay, all while updating some of the homes into fairly plausible structures. Around 2010, some art students from the area got the idea of painting murals on the walls, and the village is now something of a tourist attraction, though the flowers and puppies are fading. And the neighborhood has not just electricity and bus service, but solar-powered street lamps and a new pavilion and residents with smart phones, not to mention government-issued wayfaring signs for visitors. Down the hill, the newly built middle school is actually pretty grand.

As an outsider, it’s hard to know what to make of all this. What little information I have is gleaned from blogs. Who lives here now, and why? How poor are they? Is the ownership in dispute? What does the future hold? I have no idea, and I didn’t feel comfortable asking questions of the few residents we saw around. When you find yourself having a cheap holiday in other people’s misery, sometimes it’s better not to pry.

Tea at the temple

At its top, The Ant Village opens out onto the trails crisscrossing Inwangsan Mountain. Had we been feeling ambitious, we might have made the long hike up and over to the Jongno side of the mountain, descending into trendy Hyoja-dong. The sun and relative warmth were enticing, but it was already afternoon, and we decided instead to stick with our chosen neighborhood, walking through the woods, past an open view of Train Rock — it’s a big rectangular rock, basically — and down a long staircase to Hwanhuisa Temple.

As we approached, a group of women of a certain age were gathered out front, along with a Buddhist nun, all talking and laughing. I said hello, and they all cooed at how well I spoke Korean, something that used to happen a lot when I lived in Anyang, outside Seoul, sixteen years ago, but rarely happens now until I’ve at least demonstrated something beyond annyeong haseyo. It was another throwback, and a reminder that foreigners probably don’t get out this way all that often.

My friend noted the feminine touches to the temple — Dalmatian figurines and the like — and decided it must be run by nuns. Soothing piano music played from outdoor speakers, mingling with sound of the Korean-style wind chimes. As we sat and rested on a small pavilion, a woman brought us a tray of tea and tteok with marmalade. Later, as we looked for somewhere to return the tray, we heard more women’s laughter coming from inside the main building. We set the tray down inside a doorway and continued on.

A little further on we passed another small temple, then emerged from the mountain into one of those vast, dispiriting apartment complexes that dominate so much of the Korean landscape. Director Bong Joon-ho’s first film, Barking Dogs Never Bite, from 2000, centered on stunted lives in an apartment complex much like this one. It was, in material terms, a step up from the drafty, poorly built villas we’d seen earlier, but I could see how people might choose the human-scale lumpiness of life in The Ant Village, or down among the old brick villas, over this different sort of ant farm. Koreans seem to have recognized the grimness of life in these sorts of massive apartment blocks, and newer complexes tend to be made up of clusters of slender towers, with only a few apartments per floor and spaces in between the buildings.

At last we found our way back to the main street, after passing a small English school that made me feel sorry for whatever English teachers have ended up in this strange little corner of the city. We stopped in at a Paris Baguette for some coffee and a rest, watching the old woman squatting outside the window as she roasted sweet potatoes. Across the street was the district headquarters for the conservative party, emblazoned with a huge Korean flag that loomed above several fortune-telling shops marked by swastikas. A few blocks on, past more fortune tellers and glimpses of the old city wall at the top of Inwangsan, we came to Muakjae Station, where we boarded the train and headed back to Gangnam.