Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

A long one, and the pictures aren’t up yet either, but there’s a lot to say.

La Viet en rose

On the first night of the Tet holiday, my Vietnamese friend in Saigon took me to a Latin music club. It’s true that I came to Vietnam for Tet without clear expectations of what it would entail, but this was a surprise.

Even more surprising was how good it was. The entirely Vietnamese band at stylish, candle-lit Carmen Bar — three acoustic guitars, drums, bass, percussion, keys — plays with polish and flair, everything from Latin hits to bachatas to the occasional disco number for a request. They back up a rotating set of singers with different specialties: a sexy chanteuse, a hammy lounge singer type, a trio, a heavyset guy in a sombrero backing two Filipinas until he stepped forward to do a passable Louis Armstrong imitation for “What a Wonderful World.” It could have been merely cheesy, but there was a level of musicianship and a knowingness that made even the silly bits feel sophisticated, cosmopolitan. Maybe it’s just that I don’t know about it, but I never found anything this worldly, this hip, in Bangkok, or anywhere else in Southeast Asia. Vietnamese culture has a certain depth that I find compelling.

Late in the evening, a mustachioed guitarist began to play French rock and pop from the sixties, which resonated with the mostly Vietnamese audience, especially the older people who grew up in South Vietnam when the French influence was still strong. My friend, who is a bit younger than me, knew all the lyrics to many of the songs, though she didn’t know what they meant; they were the records her parents played when she was young. Some people in their sixties got up to dance. An older woman from the audience was invited onstage to sing a rich and rousing “La Vie en Rose.” The club was less full than usual, with so many people gone to their hometowns for the holiday, but that gave the place a kind of intimacy. It felt like a private conversation, like old friends reminiscing over what was and what might have been.

Red envelopes

Of course, there’s more to Tet than Edith Piaf covers. Tet, the lunar new year, is the biggest holiday of the year in Vietnam. From Saigon, much of the population disappears to the countryside, to their home villages and elderly relatives. And they bring flowers with them — yellow flowers, mostly, sometimes whole trees with yellow flowers on them, hauled along on moterbikes from one of the many flower markets that spring up all over the city in the days before the new year. (Buying an entire tree as a holiday decoration and then throwing it out a week or two later seems crazy to me, but I’m Jewish.) Throughout Saigon, shops and buildings, streets and parks are decorated with symbols of the festival: representations of old Chinese coins, flowers, pictures and statues of monkeys for the Year of the Monkey, displays of traditional Vietnamese village life, and especially red banners with the phrase “Chúc Mừng Năm Mới,” happy new year.

In any case, our trip to Carmen Bar was Saturday night, the first night of the national holiday. The following night was the real thing, the last night of the lunar year. My friend took me to her parents’ house, where we ate on the floor because they didn’t have a table big enough for everyone, and we looked at old family pictures: of my friend and her brother as babies and as teenagers, of the aunt who was a movie star, of the French grandfather in his military uniform. Then it was time for the giving of the red envelopes, in which elders give envelopes of money and blessings to younger family members, amid much hilarity. My friends’ parents gave me an envelop too — yellow, which they said was extra special because it’s the royal color — and it contained a series of bills, which my friend’s mother explained: a 1,000-dong note (roughly a nickel), which if you give to a beggar, he won’t say thank you; a 2,000-dong note, which you can give to a beggar to get thanks; 5,000, which can get you salt for ban mi bread; 10,000, which can get you the bread itself; 20,000, which can get you a bowl of pho; and 100,000 (just under $5), which can get you a whole meal.

Later my friend’s brother and girlfriend met me on District 1’s Walking Street to watch the midnight fireworks. There I learned of the ancient Vietnamese custom of resting your arm, weary from holding up your iPad to video an empty sky, on the head of the foreigner standing in front of you. At last there were fireworks, and they were pretty good fireworks — “good, but not Sydney good,” as I heard an Australian say behind me — and then it was over, and the crowd broke up, and we went our separate ways into the Year of the Monkey.

Bác Chio

The next day, like everyone else in Saigon, I left town. Along with my friend and her two daughters, aged ten and five, I headed for the beach on Phu Quoc, a charming resort island just south of Cambodia that once held South Vietnam’s largest prison and was briefly captured by the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s.

It was fun to hang out with kids at the beach. The older one speaks English pretty well, though she’s shy about it, and the younger one understands a great deal, though she was happy to chatter away at me in Vietnamese most of the time. As the days wore on, though, she began using more English with me, starting with the moment at the beach when she held up a bunch of wet sand dripping from her two hands and declared, “It’s so yucky!” The older one called me “Uncle Josh” — “uncle” is a common term of respect for an older male, as it is in Korea — while the younger one turned that into “Bác Chio,” pronounced as something like bah jaw. We went on a snorkeling tour, and I reassured the skittish ten-year-old that she could in fact learn to snorkel in five minutes, that the coral would not slice her to bits, that there were no sharks. She and I bonded over our shared seasickness on the long boat ride. We spent a day at the beach, and then another day at a water and amusement park called Vinpearl Land, which was cheesy and ridiculous and good fun, and the bruise on my elbow from that one twisty water slide is healing nicely, thank you.

War remnants

Back in Saigon, we decided to take a tour of the Cu Chi tunnels. Cu Chi was a jungly crossroads not far from Saigon that became a Viet Cong stronghold. It became a free-fire zone, and a place where US bombers returning from sorties to the North would unload any remaining bombs before landing on aircraft carriers.

There were people down there.

The Vietnamese response was to develop a system of tunnels and booby traps as a means of survival and to continue to challenge and ensnare the enemy close to its capital in Saigon. The Cu Chi tunnels are presented as examples of the hardscrabble genius of the Vietnamese fighters and villagers — the distinction is blurry — who survived and fought there. That’s accurate as far as it goes. They turned bomb fragments into metal spikes for ingenious, terrifying booby traps that would ensnare and mangle the bodies of those who stepped on them. They sawed open unexploded bombs to get the materials to make anti-tank mines. They dug tunnels, some as much as ten meters deep, all by hand, and created bamboo breathing tubes that they camouflaged under fake termite mounds. They dug special tunnels to dissipate the smoke from cooking fires. They made sandals out of old tires, and for the rainy season, when their steps would leave tracks, they devised backward sandals that made it look like they were going the opposite way.

It’s all very impressive and very clever, and if I were a GI sent into that jungle to look for VC, I would have been terrified all the time: every step could mean agonizing pain or death, and VC could pop out of a hidden hole just about anywhere and shoot you in the gut or face or slash you with a hoe. But then you realize that this was a response to massive aerial bombardment, and that the US soldiers came in with hand grenades and rocket launchers and flamethrowers and teargas canisters and sniffing dogs, while the Vietnamese hid in holes in the ground and hoped the bombing would stop before they ran out of air.

The Cu Chi experience is made all the more vivid by the rattle and pop of gunfire from the attached shooting range, where you can try out some of the weapons that were used in the war. I took the opportunity to fire an M-16 and an AK-47, just to feel what it’s like to use them. They’re both easy weapons to fire, with a soft trigger and not too hard a kick.

A couple of days later, I went to the War Remnants Museum in Saigon, which presents the war from a Vietnamese Communist perspective, propaganda and all. The displays accuse the Americans, rightly, of counting any dead Vietnamese as Viet Cong and ignoring civilian casualties, but they tend to count any dead Vietnamese as patriots. There is, of course, no mention of any North Vietnamese or Viet Cong acts of torture or aggression, which can lead to odd gaps: a prison display that includes tiger cages used by the South but never mentions American POWs; an odd gap between the peace agreement establishing a North and South Vietnam and a war in which America was defending southern “puppets,” the actual term the museum uses for the government of South Vietnam. There’s a display aimed at branding Senator Bob Kerrey a war criminal — he probably was — that suggests he confessed, which he never did. (It was good to have Wikipedia on my phone as I walked around the museum.) There’s a reference to the Bertrand Russell Tribunal as if it were an important international body rather than an informal gathering of leftist philosophers in France in 1967.

The propaganda is unnecessary: the accumulated evidence of American stupidity and brutality is overwhelming. It’s hard to look at the accumulated evidence — the tonnage of bombs dropped, the pictures of victims, of suffering Vietnamese, suffering GIs — and not see that this was something the US created. I am not sure that anything could justify the kind of bombing we did in Vietnam, incinerating whole communities. I think the bombing we did against the Nazis and the Japanese in World War II went well beyond what was right or justifiable, but at least we were doing it as part of a larger war that had purpose. Even in Korea that was more true than not. but our strategy in Vietnam never made much sense. We were defending first a terrible, unpopular, ineffectual regime, and then no regime at all. And we were fighting in a place of minimal strategic importance — unlike Korea, which was sandwiched between Mao’s China, the Soviet Union, and Japan. There was no one brave or wise enough to see that Vietnam was more like Angola or Afghanistan, less like Korea or Berlin — and that was because McCarthy’s witch hunt had driven all the China scholars from government, blaming them for China’s fall to communism, as if the failure of the Kuomintang were somehow the result of biased academic writing.

Yes, the US was probably right to try to block the spread of communism in Vietnam, but not through full-scale military intervention. Yes, the US was right to fear that its failure there would send a worrying message of weakness to our allies around the world, in Taiwan and South Korea and Japan and Greece and West Germany, which is the US should never have staked its reputation on Vietnam in the first place. The US should have done what it did in China, which was to recognize the absence of any viable counterweight to the communist forces and give up. But that was politically impossible in post-McCarthy America. The suffering we inflicted on the Vietnamese people in the name of a flawed geopolitical strategy is unconscionable, as is a lot of what we did in the process: My Lai, Agent Orange, Napalm, ignoring torture in South Vietnamese prisons, and much more.

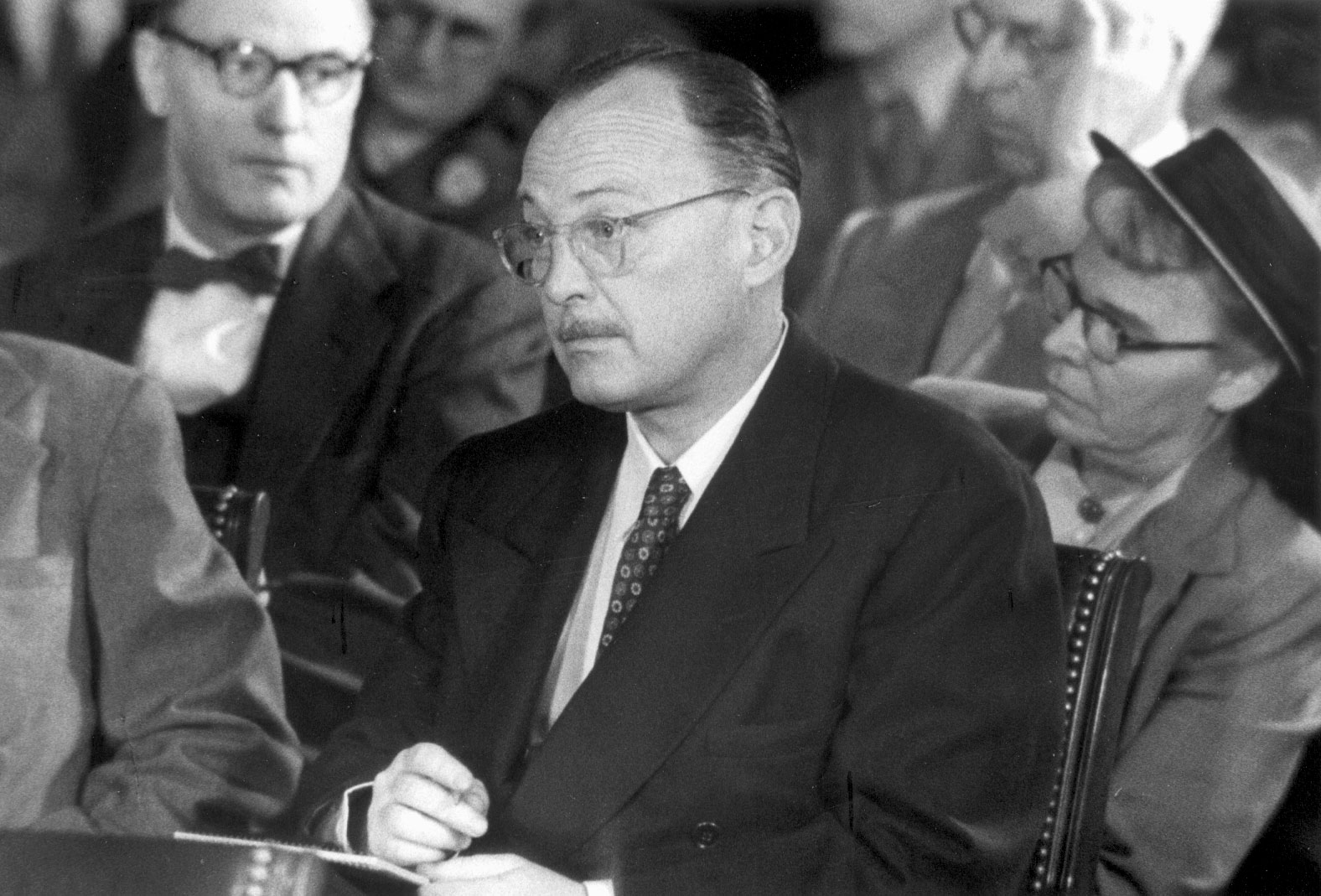

These are old debates, but maybe worth thinking about if you haven’t done so in detail. The issues are still relevant. “It became clear then,” said Robert McNamara, the principal architect of the war, speaking in 1995, “and I believe it is clear today, that military force — especially when wielded by an outside power — cannot bring order in a country that cannot govern itself.” Is he right? If so, what does that tell us about how to deal with Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan?

What stays with me, though, are the pictures of American GIs, muddy and terrified and miserable. Yes, what the Vietnamese endured was far worse, but like it or not, the GIs are my people. My father could have been one of those GIs, but he engineered a way out of the war. My ex-girlfriend’s father went to the front, and he spent the rest of his life waking up screaming at night.

A holiday in Cambodia

In speaking to my Vietnamese friend about the war, we could agree that for all their flaws, the major leaders on both sides — Ho Chi Minh, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon — had been trying, in their flawed ways, to do the right thing. And we agreed that the same cannot be said for Pol Pot, who was just batshit insane and about as evil as they come, and who managed to make enemies of the United States and communist Vietnam both. Tomorrow I will be on a bus to Phnom Penh, the capital of what was once the Khmer Rouge’s nightmare state of Kampuchea.

No, I’m not in Southeast Asia on a war-and-genocide tour. But I want to understand this part of the world as I travel it, and these things, as much as the mountains and temples and culinary traditions, are part of what has shaped these nations and their people today. So I’ll go, and I’ll see the height of Khmer genius at Angkor Wat, and I’ll see the depths of Khmer depravity too. The world is a complicated place.