As a destination, Daegu doesn’t have much to recommend it. I’d come down from Seoul for one reason only: to see my friend Dong-Won Kim accompany the great pansori singer Bae Il-dong. So when we arrived at the address Dong-Won had sent us, far on the outskirts of Daegu, and found ourselves in the office of a loan shark next door to a tire shop, I was not amused.

After some frantic messaging, we got an updated address that took us deep into one of those ubiquitous beige apartment complexes, and at last we spotted Dong-Won waving his arms on the far side of a parking lot. With Korean musicians, it’s always a little yeogi-cheogi, a little here and there. But perched above a GS25 convenience store in the unlikeliest spot was this delightful little music cafe with an upright bass against the wall and a pair of master musicians getting ready to perform.

We were exactly nowhere, which is where a lot of the best things happen.

Intangible

We arrived in the middle of a screening of the documentary Intangible Asset No. 82, which tells the story of an Australian jazz drummer who comes to Korea in search of an elderly percussionist he’s obsessed with. Dong-Won becomes his guide, introducing him to some of Korea’s finest musicians — including Bae Il-dong — and providing about the best possible introduction to Korean traditional music.

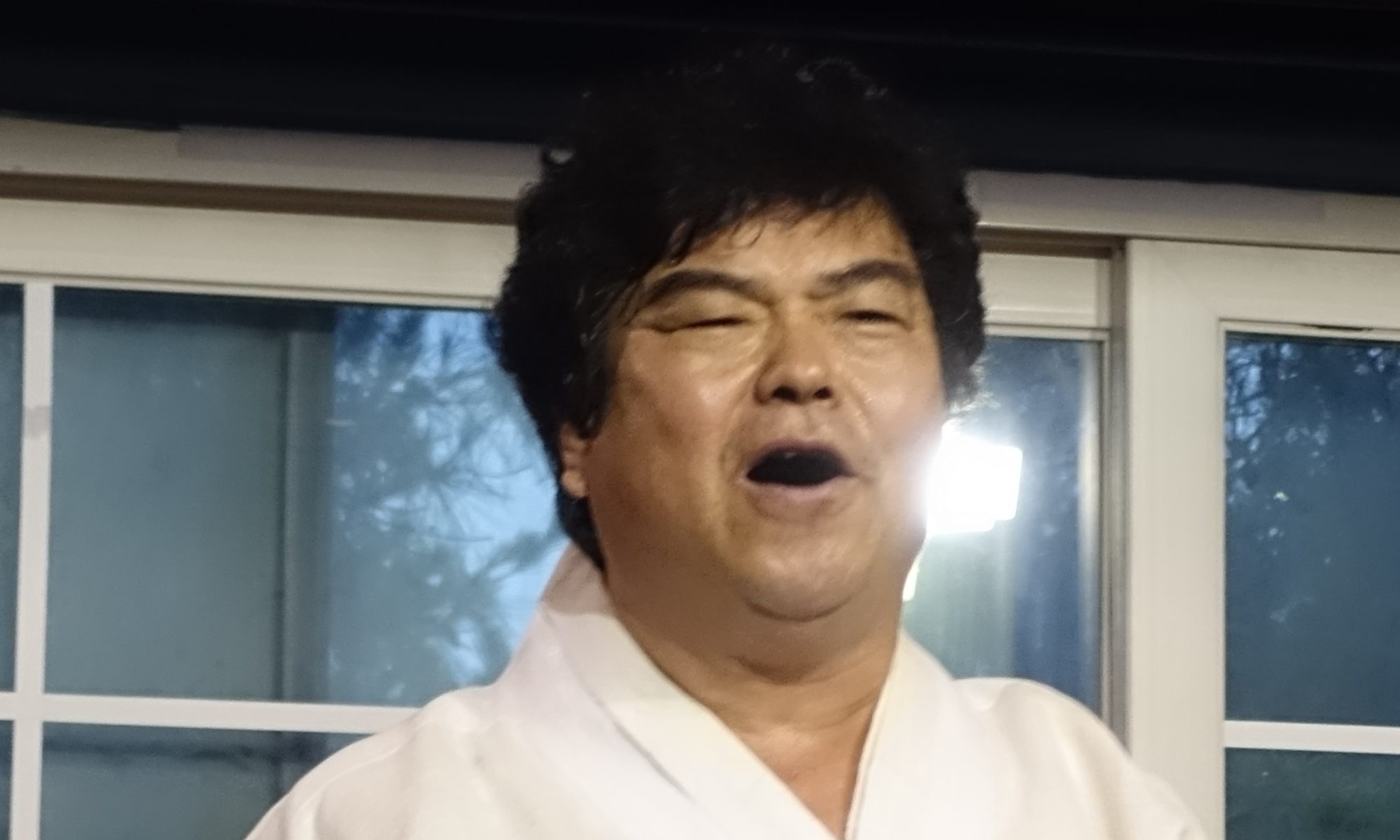

When the film was over, I at last got to hear Bae Il-dong in person. His voice is an extraordinary instrument, raw but supple. There’s nothing showbiz about what he does. His only real trick is absolute mastery of his art form born from total dedication. He once spent seven years singing at a waterfall to develop his voice and find his sound.

Pansori is a storytelling art form, born as a communal activity among the lower classes in Southern Korea in the 19th century, full of humor and pathos, moments of sorrow and moments of joy. Il-dong sang a famous piece in which an old, blind man is reunited with the daughter he thinks he sent to her death — a shock so profound that he recovers his sight. The performance was vivid enough that my friend could grasp the gist of it without understanding the words.

As for me, I was startled by how much I did understand. During the film and the concert — which had a lot of lecture mixed in — I became my friend’s Dong-Won, leaning in to let him know what was going on. And for the first time, I found myself following along with the words of the pansori, even laughing at a few of the jokes I caught.

Community

After the concert, heaps of food were brought in — hearty, traditional Korean stuff — and everybody stayed on to eat and drink together. Dong-Won explained that Korean music is communal, in which the musicians don’t just transmit emotion to the audience, but share in a collective emotional experience.

After a little while, an emcee got up and began to chatter. Dong-Won explained that he was actually a fine musician and dancer who’s known for his skills as a clown and comedian, and soon it was clear what he was up to. He started pulling people up from the audience and getting them to sing: traditional songs, sometimes with Dong-Won pressed into rhythm accompaniment or with a guitarist picking out some backing chords. And these people knew their stuff. No one was at Bae Il-dong’s level, but these were people who’d spent time learning Korean traditional music and dance. Or some of them were, anyway. As the evening went on, the emcee made sure everyone got a chance to do something, whether it was singing an old pop tune or doing a little dance. I got up to dance too, showing off what I can remember of my Korean moves and then putting on the traditional grandfather mask and doing the requisite drunkard’s dance.

Eventually my friend grabbed a guitar and sang some classic rock — Oasis, Pink Floyd — while Dong-Won played the box and I had some fun thumping along on the janggu. It’s not every day you get to play with a member of Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Ensemble, so you’ve got to grab the opportunity when it comes. My friend sang, I drummed, people danced.

Eventually my friend grabbed a guitar and sang some classic rock — Oasis, Pink Floyd — while Dong-Won played the box and I had some fun thumping along on the janggu. It’s not every day you get to play with a member of Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Ensemble, so you’ve got to grab the opportunity when it comes. My friend sang, I drummed, people danced.

The road to nowhere

I said at the start that the best things often happen exactly nowhere. I’m thinking of a night in the little Burmese trekking village of Kalaw, where some guys at the back of a bar called Hi Snacks & Drinks got out acoustic guitars and sang the night away. I’m thinking of a pansori festival I saw on the banks of a river somewhere in Jeolla province when I lived here as a teacher. I’m thinking of a night spent in an obscure temple with just one other person — my Swiss shaman friend — sitting by the pagoda under the moonlight and listening to the chorus of cicadas and frogs. I’m thinking of northern Laos, where nothing happens, and of the house where I grew up in Marin County, California.

At the heart of Korean music is cyclicality: strong and soft, yang and yin, breath in and breath out, in every note and movement. Right now I’m leading just about the most yang existence imaginable, living in Gangnam and working for Samsung, but there’s an undertow of yin that’s calling to me.

“So save your money and then run away!” Dong-Won said, when we had a chance to talk about it.

Maybe.

“You and I have the same blood type,” he said. “Blood type W. Blood type wind.”

In the film, Dong-Won used a different metaphor from nature: you can be a lake, or you can be a river. A lake stays where it is, but a river is always carving out new paths, flowing where it’s never flowed before. Yeogi-cheogi.

He could have added that a river does this by letting go, not by force of will. I suppose that to heed the call of the yin is first of all to stop worrying about the yang. Things will go how they go. My life has taken enough surprising turns that if I go back over it in five-year increments, I realize that I never really had any idea what was coming. Why should now be any different?

Also published on Medium.